Silicon germanium was a novel, new semiconductor that relied on established technology, resulting in massive cost savings over other materials. SiGe chips emerged as a variant of the stalwart complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) transistors used in IBM’s chips for the previous 20 years.

TU Wien (Vienna) has succeeded in developing a new type of material that can be used in chip technology. This allows for faster, more efficient computers as well as new types of quantum devices.

Current chip technology is largely silicon-based. A trace amount of germanium is used in very specific components. However, there are several compelling reasons to use higher germanium contents in the future: In terms of energy efficiency and achievable clock frequencies, the compound semiconductor silicon-germanium has significant advantages over today’s silicon technology.

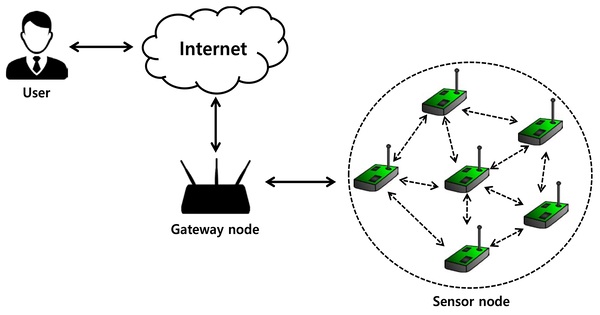

The main problem here is to establish contacts between metal and semiconductor on a nanoscale in a reliable way. This is much more difficult with a high proportion of germanium than with silicon. The team at TU Wien, however, together with research teams from Linz and Thun (Switzerland), has now shown that this problem can be solved—with contacts made of crystalline aluminum of extremely high quality and a sophisticated silicon germanium layer system. This enables different interesting contact properties—especially for optoelectronic and quantum components.

Our experiments show that these contact points can be produced in a reliable and easily reproducible way. The technological systems you need to do this are already being used in the chip industry today. So, this is not just a laboratory experiment, but a process that could be used relatively quickly in the chip industry.

Walter Weber

The problem with oxygen

“Every semiconductor layer is automatically contaminated in conventional processes; this simply cannot be prevented at the atomic level,” says Masiar Sistani from the Institute for Solid State Electronics at TU Wien. First and foremost, it is oxygen atoms that accumulate very quickly on the surface of the materials—an oxide layer is formed.

With silicon, however, this is not a problem: silicon always forms exactly the same kind of oxide. “With germanium, however, things are much more complicated,” explains Masiar Sistani. “In this case, there is a whole range of different oxides that can form. But that means that different nanoelectronic devices can have very different surface compositions and therefore different electronic properties.”

If you now want to connect a metallic contact to these components, you have a problem: Even if you try very hard to produce all these components in exactly the same way, there are still inevitably massive differences—and that makes the material complex to handle for use in the semiconductor industry.

“Reproducibility is a big problem,” says Prof. Walter Weber, the head of the Institute for Solid State Electronics, TU Wien. “If you use germanium-rich silicon germanium, you can’t be sure that the electronic component, after you’ve put contacts on it, will really have the characteristics you need.” As a result, this material is only used to a limited extent in chip production.

That is a pity, because silicon germanium would have decisive advantages: “The charge carrier concentration is higher, especially positive charge carriers, the so-called ‘holes’, can move much more efficiently in this material than in silicon. The material would therefore allow much higher clock frequencies with increased energy efficiency than our current silicon chips,” says Lukas Wind, a doctoral student in Walter Weber’s research group.

The ‘perfect’ interface

Now, however, the research team has been able to show how the problem can be solved: They found a method to create perfect interfaces between aluminum contacts and silicon germanium components on an atomic scale. In a first step, a layer system is produced with a thin silicon layer and the actual material from which the electronic components are to be made—the silicon-germanium.

By heating the structure in a controlled manner, a contact can now be created between the aluminum and the silicon: At around 500 degrees Celsius, distinctive diffusion occurs, the atoms can leave their place and start to migrate. Silicon and germanium atoms move into the aluminum contact relatively quickly, and aluminum fills the vacated space.

“The diffusion dynamics in the layer system used thus create an interface between aluminum and the silicon germanium with an extremely thin silicon layer in between,” explains Masiar Sistani. Through this manufacturing process, oxygen atoms never have the opportunity to get to this atomically sharp and highly pure interface.

“Our experiments show that these contact points can be produced in a reliable and easily reproducible way,” says Walter Weber. “The technological systems you need to do this are already being used in the chip industry today. So, this is not just a laboratory experiment, but a process that could be used relatively quickly in the chip industry.”

The decisive advantage of the presented manufacturing process is that high-quality contacts can be produced regardless of the silicon-germanium composition. “We are convinced that the presented abrupt, robust and reliable metal-semiconductor contacts are highly interesting for a variety of new nanoelectronic, optoelectronic and quantum devices,” says Walter Weber.