One of the longest-held theories concerning the ancestry of contemporary birds has been challenged by the discovery of fossilized pieces of a skeleton concealed inside a grapefruit-sized rock.

One of the fundamental skull characteristics that distinguishes 99% of modern birds a movable beak evolved before the great extinction event that wiped out all massive dinosaurs, 66 million years ago, according to researchers from the University of Cambridge and the Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht.

This discovery shows that when modern birds originated, the skulls of ostriches, emus, and their cousins underwent “reverse” evolution, returning to a more primordial state.

The Cambridge scientists called the new species of giant ancient bird Janavis finalidens after the bones from its palate, or the roof of the mouth, which they were able to identify using CT scanning techniques.

One of the very last toothed birds to ever exist, it lived at the very end of the Age of Dinosaurs. The arrangement of its palate bones demonstrates that this “dino-bird” had a maneuverable, nearly identical beak to that of the majority of current birds.

It had been believed for more than a century that the mechanism allowing a movable beak originated after the demise of the dinosaurs. The latest discovery, which was published in the journal Nature, suggests that we should reevaluate our assumptions about how the contemporary bird skull developed.

Based on how their palate bones are arranged, the roughly 11,000 bird species that exist on Earth today are divided into one of two major groupings. The palaeognath, or “ancient jaw,” group includes ostriches, emus, and their cousins. This means that, like humans, the palate bones in these animals have fused together into a single mass.

All other bird species are categorized as belonging to the neognath, or “modern jaw,” group because of the movable joint that connects their palate bones. Their beaks become much more agile as a result, making them useful for nest construction, grooming, food gathering, and defense.

The two groups were originally classified by Thomas Huxley, the British biologist known as ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ for his vocal support of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. He classified all extant birds in 1867 into two groups based on their jaws: “ancient” and “modern.” Huxley believed that contemporary birds originally had the ‘ancient’ jaw arrangement and that the ‘modern’ jaw developed later.

“This assumption has been taken as a given ever since,” said Dr. Daniel Field from Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences, the paper’s senior author. “The main reason this assumption has lasted is that we haven’t had any well-preserved fossil bird palates from the period when modern birds originated.”

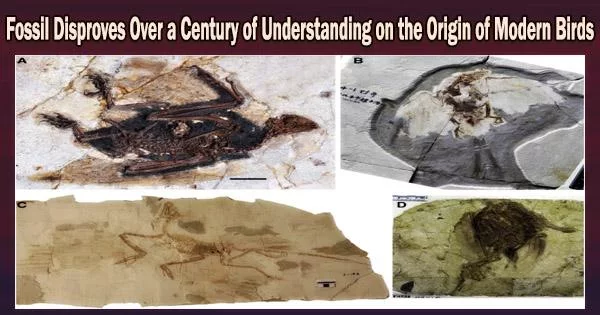

The Janavis fossil, discovered in a limestone quarry not far from the Belgian-Dutch border in the 1990s, underwent its initial examination in 2002. It was created 66.7 million years ago, during the end of the dinosaur era.

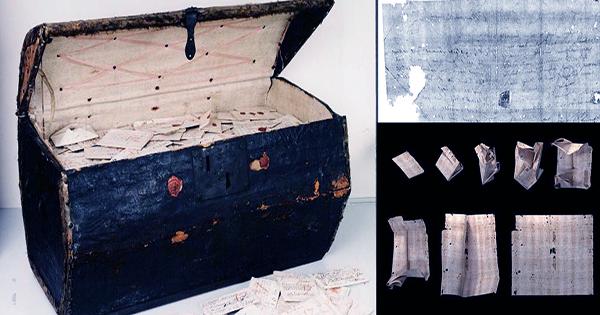

Scientists at the time could only describe the fossil based on what they could see from the outside because it is enclosed in rock. The unremarkable-looking fossil was placed back in storage after they described the bone fragments protruding from the rock as pieces of a cranium and shoulder bone.

Nearly 20 years later, the fossil was loaned to Field’s group in Cambridge, and Dr Juan Benito, then a PhD student, started giving it another look.

“Since this fossil was first described, we’ve started using CT scanning on fossils, which enables us to see through the rock and view the entire fossil,” said Benito, now a postdoctoral researcher at Cambridge, and the paper’s lead author.

“We had high hopes for this fossil it was originally said to have skull material, which isn’t often preserved, but we couldn’t see anything that looked like it came from a skull in our CT scans, so we gave up and put the fossil aside.”

During the early days of Covid-19 lockdown, Benito took the fossil out again. “The earlier descriptions of the fossil just didn’t make sense there was a bone I was really puzzled by. I couldn’t see how what was first described as a shoulder bone could actually be a shoulder bone,” he said.

“It was my first in-person interaction in months: Juan and I had a socially distanced outdoor meeting, and he passed the mystery fossil bone to me,” said Field, who is also the Curator of Ornithology at Cambridge’s Museum of Zoology. “I could see it wasn’t a shoulder bone, but there was something familiar about it.”

“Then we realised we’d seen a similar bone before, in a turkey skull,” said Benito. “And because of the research we do at Cambridge, we happen to have things like turkey skulls in our lab, so we brought one out and the two bones were almost identical.”

The researchers came to the conclusion that the unfused “modern jaw” condition, which turkeys share, arose before the “ancient jaw” condition of ostriches and their relatives after realizing the bone was a skull bone rather than a shoulder bone. Ostriches and their relatives’ fused palates must have developed at some point after modern birds had already been established, for an unidentified reason.

A toothless beak and a movable upper jaw are two of the major traits we use to distinguish modern birds from their dinosaur ancestors. The jaw anatomy of Janavis finalidens is that of a contemporary, mobile bird, despite the fact that it still retained teeth, making it a pre-modern bird.

“Using geometric analyses, we were able to show that the shape of the fossil palate bone was extremely similar to those of living chickens and ducks,” said Pei-Chen Kuo, a co-author of the study. Added co-author Klara Widrig: “Surprisingly, the bird palate bones that are the least similar to that of Janavis are from ostriches and their kin.” Both Kuo and Widrig are PhD students in Field’s lab at Cambridge.

“Evolution doesn’t happen in a straight line,” said Field. “This fossil shows that the mobile beak a condition we had always thought post-dated the origin of modern birds, actually evolved before modern birds existed. We’ve been completely backwards in our assumptions of how the modern bird skull evolved for well over a century.”

While the entire bird family tree does not need to be redone, the researchers claim that this discovery does change our understanding of a crucial evolutionary trait of contemporary birds.

And what happened to Janavis? It perished in the global extinction event that occurred at the end of the Cretaceous epoch, along with the huge dinosaurs and other toothed birds. According to the experts, this could be a result of its size: Janavis was around the size of a contemporary vulture and weighed about 1.5 kg.

It’s likely that smaller animals like the ‘wonderchicken’, identified by Field, Benito, and colleagues in 2020, which comes from the same area and lived alongside Janavis had an advantage at this point in Earth’s history since they had to eat less to survive. After the asteroid hit the Earth and threw off the food supply systems around the world, this would have been advantageous.

The research was supported in part by the American Ornithological Society, the Jurassic Foundation, the Paleontological Society, and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).