Robotics researchers, engineers, and materials scientists showed it is possible to make programmable, nonelectronic circuits that control the actions of soft robots by processing information encoded in bursts of compressed air. Add analog and air-driven to the list of control system options for soft robots.

In a study published online, robotics researchers, engineers, and materials scientists from Rice University and Harvard University showed it is possible to make programmable, nonelectronic circuits that control the actions of soft robots by processing information encoded in bursts of compressed air.

“Part of the beauty of this system is that we’re really able to reduce computation down to its base components,” said Rice undergraduate Colter Decker, lead author of the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He said electronic control systems have been honed and refined for decades, and recreating computer circuitry “with analogs to pressure and flow rate instead of voltage and current” made it easier to incorporate pneumatic computation.

Decker, a senior majoring in mechanical engineering, constructed his soft robotic control system primarily from everyday materials like plastic drinking straws and rubber bands. Despite its simplicity, experiments showed the system’s air-driven logic gates could be configured to perform operations called Boolean functions which are the meat and potatoes of modern computing.

The biggest achievement in this work is the incorporation of both digital and analog control in the same system architecture, ones, and zeroes that you think of in a traditional computer. But we can also bring in analog capabilities, things that are continuous. That allows us to really simplify the overall system architecture and achieve new capabilities that weren’t accessible in prior work.

Colter Decker

“The goal was never to entirely replace electronic computers,” Decker said. He said there are many cases where soft robots or wearables need only be programmed for a few simple movements, and it’s possible the technology demonstrated in the paper “would be much cheaper and safer for use and much more durable” than traditional electronic controls.

As a freshman, Decker began working in the lab of Daniel Preston, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Rice. Decker studied fluidic control systems and became interested in creating one when he won a competitive summer research fellowship that would allow him to spend a few months working in the lab of Harvard chemist and materials scientist George Whitesides.

The project turned into a months-long collaboration between the two research groups, and Decker had nine co-authors on the study, including co-corresponding authors Preston and Whitesides.

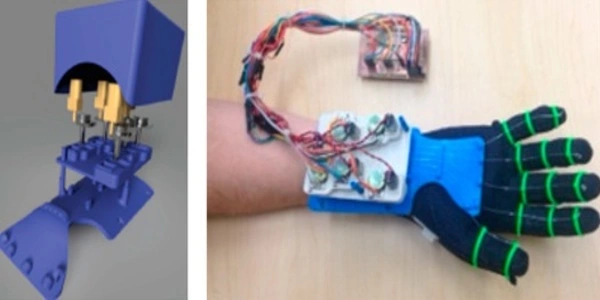

Decker and colleagues created two components, a piston-like actuator that translates air pressure into mechanical force and a valve that can be switched between two states – off and on. The components were made from parts that included plastic drinking straws, flexible plastic tubing, rubber bands, parchment paper, and thermoplastic polyurethane sheets that could be bonded together with a desktop heat press or a hot iron.

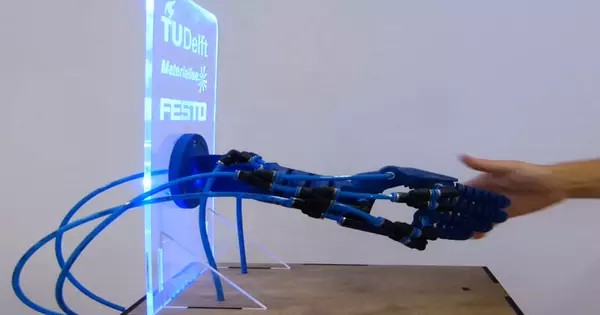

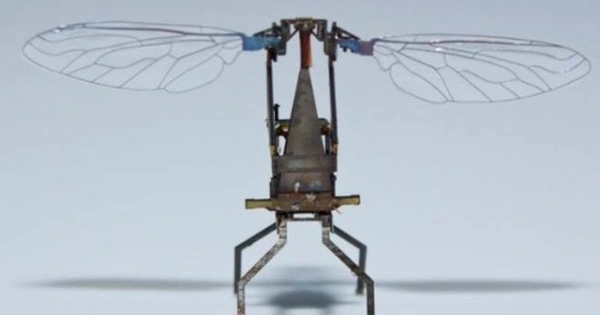

The research team showed the two components could be combined in a single device, a bistable valve that operates like a switch and uses air pressure as both input and output. A specific amount of air pressure is needed to flip the switch between off and on states. The valves are held closed by rubber bands, and they are programmed by adding or subtracting rubber bands, which changes the amount of pressure required for activation. In tests, Decker showed the circuits could be used to control a soft, hand-shaped robot, a pneumatic cushion, and a shoebox-sized robot that could walk a preprogrammed number of steps, retrieve an object and return to its starting location.

“The biggest achievement in this work is the incorporation of both digital and analog control in the same system architecture,” said Preston. Having both means the pneumatic control circuits can be programmed digitally, with the “ones and zeroes that you think of in a traditional computer. But we can also bring in analog capabilities, things that are continuous,” he said. “That allows us to really simplify the overall system architecture and achieve new capabilities that weren’t accessible in prior work.”

It is rare for an undergraduate to be the lead author of a study in a journal as prestigious as the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, but Preston said Decker’s success was no fluke.

“The undergraduates at Rice are truly top-notch, and Colter, in his case, actually has risen to essentially what I would say is the level of a Ph.D. student in terms of some of his output as an undergraduate researcher,” Preston said.