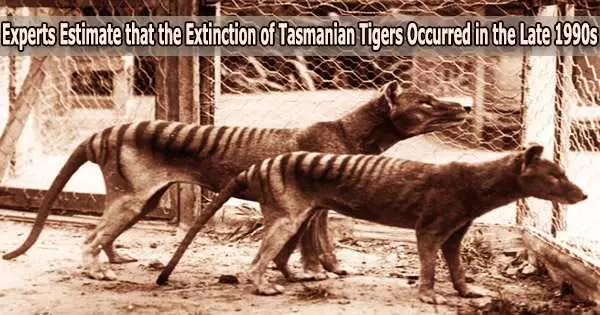

An international team of scientists under the direction of the University of Tasmania have reexamined the disappearance and potential reemergence of the Tasmanian tiger thylacine. The final thylacine to be confirmed killed in the wild occurred in 1930, and the final animal to pass away in captivity in a zoo in Tasmania in 1936.

Although no captured animals or pictures have been provided to demonstrate its survival, sightings have continued on a regular basis ever since throughout Tasmania.

The researchers intended to mimic the most likely last refuges of the iconic predator because it was possible that the creature had lasted much past its insertion and ultimate removal from the endangered species list with an official label of “extinct.”

In the paper, “Resolving when (and where) the Thylacine went extinct,” researchers modeled 1,237 reported sightings from 1910 to the present day.

Researchers used every available source for the study, which was published in Science of The Total Environment, including records from government archives, reports that were published, museum collections, newspaper articles, contemporary correspondence, private collections, and various other citations and testimony. The team even poured over microfilm records to compile their sighting database.

Next, each observation was dated, geotagged, quality-rated, and categorized by type (physical specimen, expert sighting, other observations, tracks). Using this curated sighting database, researchers mapped the sighting locations over time, taking into account that “…extinction often progresses via an intermediate process of range contractions and spatially heterogenous declines, themselves driven by a variable local intensity of threats like habitat change and hunting.”

The final database contained 1,237 entries, including 429 expert sightings from former bushmen, scientists, or officials and 99 physical documents. The other submissions were from members of the general public. Two models were developed, one with an ideal linear estimator and the other with a statistical extinction date.

This led to median extinction dates between 1999 and 2008, with the most likely (overlapping) end date around the late 1990s. Unless you’re a Tasmanian tiger lover hoping they might still exist, this finding is very contentious. However, when restricting data to physical specimens, the models indicated extinction by 1941.

While the Tasmanian tiger is unlikely to be hidden in the temperate woods of the island right now, the researchers contend that the extinction year was probably considerably closer than previously thought.

There are numerous instances of grouped sightings with nearly identical visual descriptions that were reported to the authorities without the interrelationships becoming obvious.

In the six decades between 1940 and 1999, when the data are taken as a whole, the annual number of reports was essentially steady, but from 2000 to the present, it significantly decreased.

This raises the idea that a small population of thylacines avoided extinction by moving to more remote locations and vanished before conclusive proof could be obtained a few years later.