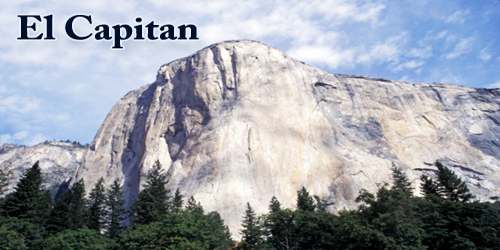

El Capitan (Spanish: El Capitán; The Captain or The Chief), is perhaps the most sublime feature in all of Yosemite Valley, and second only to Half Dome among Yosemite’s most recognized features. It is also known as El Cap. The granite monolith is about 3,000 feet (914 m) from base to summit along its tallest face and is a popular objective for rock climbers. It is 1,000 feet higher than the face of Half Dome. From the Tunnel View lookout, El Capitan is the massive cliff on the left side of the valley, standing notably higher than everything else in the view from this vantage point. El Capitan is featured on a United States quarter-dollar coin minted in 2010 as part of the America the Beautiful Quarters series.

The formation was named “El Capitan” by the Mariposa Battalion when they explored the valley in 1851. El Capitan (“the captain”, “the chief”) was taken to be a loose Spanish translation of the local Native American name for the cliff, variously transcribed as “To-to-kon oo-lah” or “To-tock-ah-noo-lah” (Miwok language). It is unclear if the Native American name referred to a specific tribal chief or simply meant “the chief” or “rock chief”.

According to one source, the original English name was “Crane Mountain,” not for the reason given above but for the sandhill cranes that entered the valley by flying over the top of El Capitan. And finally, Hutchings’ Illustrated 1, no. 1st July 1856, called it “Giant Tower.”

The monolith and scenic valley attracted artists, including painters and photographers. Their works helped make the area well known, and in 1890 Yosemite National Park was created. The top of El Capitan can be reached by hiking out of Yosemite Valley on the trail next to Yosemite Falls, then proceeding west. For climbers, the challenge is to climb up the sheer granite face. There are many named climbing routes, all of them arduous, including Iron Hawk and Sea of Dreams.

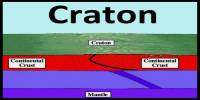

El Capitan is composed almost entirely of a pale, coarse-grained granite emplaced approximately 100 mya (million years ago). In addition to El Capitan, this granite forms most of the rock features of the western portions of Yosemite Valley. A separate intrusion of igneous rock, the Taft Granite, forms the uppermost portions of the cliff face.

A third igneous rock, diorite, is present as dark-veined intrusions through both kinds of granite, especially prominent in the area known as the North America Wall.

For many years it was believed that climbing the mountains’ vertical walls was impossible. In 1957, however, Warren Harding led an expedition to scale the peak. The group focused on the prow that formed where the southeastern and southwestern faces meet; it became known as the Nose. For 45 days over more than one year, they established a route by inserting pitons and drilling bolt holes for the fixed ropes.

On 12th November 1958, Harding and two others finally summited the mountain. Since then El Capitan has become popular with climbers, and in 2017 Alex Honnold became the first to ascend the mountain without using ropes; his climb was documented in Free Solo (2018). In addition, hikers are able to summit via an arduous trail.

Along with most of the other rock formations of Yosemite Valley, El Capitan was carved by glacial action. Several periods of glaciation have occurred in the Sierra Nevada, but the Sherwin Glaciation, which lasted from approximately 1.3 mya to 1 mya, is considered to be responsible for the majority of the sculpting. The El Capitan Granite is relatively free of joints, and as a result, the glacial ice did not erode the rock face as much as other, more jointed, rocks nearby. Nonetheless, as with most of the rock-forming Yosemite’s features, El Capitan’s granite is under enormous internal tension brought on by the compression experienced prior to the erosion that brought it to the surface. These forces contribute to the creation of features such as the Texas Flake, a large block of granite slowly detaching from the main rock face about halfway up the side of the cliff.

There are no permits or use fees required to climb El Capitan, other than the standard park entrance fee. Bivies on the walls around Yosemite Valley do not require a Wilderness Permit. Climbing can be done year-round, but the big walls are most often climbed Spring-Fall. Summer months can be exceedingly hot on those south-facing walls! Hikers attempting to reach the summit via the Yosemite Falls Trail in winter will find the trail closed about a few miles from the trailhead due to avalanche dangers.

The speed climbing record for the Nose has changed hands several times in the past few years. The sub two hour and current record of 1:58:07 was set on 6th June 2018, by Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell after two other record-breaking climbs in the days before. Mayan Smith-Gobat and Libby Sauter broke the speed record for an all-women team, with a time of 4:43, on 23rd October 2014.

Over thirty fatalities have been recorded between 1905 and 2018 while climbing El Capitan, including seasoned climbers. Critics blame a recent increase of fatalities (five deaths from 2013 to 2018) in part on the increased competition around timed ascents, social media fame, and “competing for deals with equipment manufacturers or advertisers”.

Camping is allowed at the base only in designated campgrounds (Camp 4 is the closest), fees apply. Overnight stays enroute on the walls are not restricted or subject to permits. You can likewise camp at the summit without need for permit, though this is at the discretion of the rangers. Climbers are generally not expected to have permits for overnight stays on the summit, but hikers coming from the trail are. Fires are allowed (but discouraged) at the summit.

Information Sources: