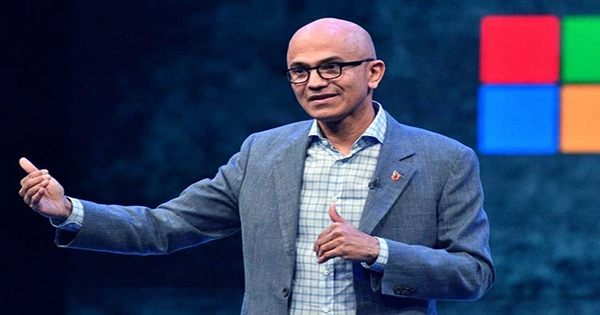

It’s easy to forget that Microsoft was once a stumbling block, especially with its current market capitalization of $2 trillion. The corporation almost completely missed the mobile boat around 2010, four years before Satya Nadella would succeed Steve Ballmer as CEO. When Nadella joined Microsoft as CEO eight years ago, his objective seemed to be to ensure that the business didn’t make the same cloud-related mistakes. One approach to achieve this is to throw money at the problem and just buy the businesses to make the path easier.

According to Crunchbase data, Microsoft has purchased 250 companies since its creation, but the majority of the largest purchases, totaling $5 billion or more, have occurred under Nadella’s tenure. Nokia and aQuantative were the two outliers, both of which were launched during Ballmer’s tenure and failed miserably. With Nadella in the corner office, the $69 billion Activision merger announced in January, the $26 billion LinkedIn deal in 2016, and the $20 billion purchase of Nuance Communications last year all transpired.

The issue for Nadella and Microsoft in the next years will be to balance increased governmental supervision with the company’s broad diversification. As Jared Spataro, corporate vice president for Office 365, pointed out in his TC Sessions: SaaS interview last year, Microsoft has long had the resources and capability to handle multiple large businesses: “The context for Microsoft had been our ability to develop multiple, very large businesses that ran in parallel.” So this notion that we had many multibillion-dollar businesses, such as the Windows and Office businesses… Even a productivity-related server business [definitely helped].”

As the company’s market capitalization has increased, so has the size of its resources. Consider that the company’s public market worth has risen from a little over $800 billion to over $2 trillion since I covered Nadella’s five-year anniversary in 2019. That kind of growth opens up a lot of possibilities, which Nadella has taken full advantage of.

We now take the cloud for granted as a means of delivering and developing software, but it wasn’t always so. Companies like Microsoft, for example, used to sell the majority of their software in boxes or as big on-prem installs within client data centers less than a decade ago. As the firm began to consider what the future of computing may look like about 2012, it became evident that software will eventually migrate to the cloud. Microsoft would have to go through a long process of changing internal processes and persuading customers that the cloud was a better way to offer software.