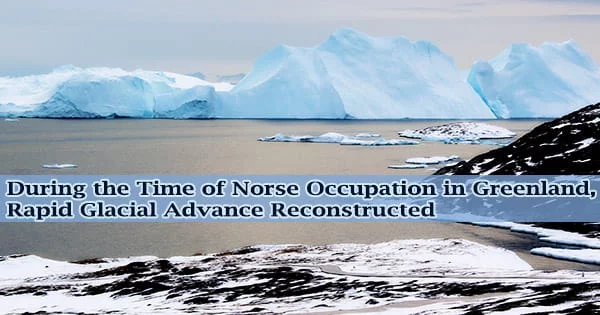

The Greenland Ice Sheet is the world’s second-largest ice sheet, and it has the potential to considerably contribute to global sea-level rise in a warming world. Understanding the Greenland Ice Sheet’s long-term record, which includes both glacial advance and retreat, is crucial for evaluating methodologies that forecast future ice-sheet scenarios. This reconstruction, however, can be quite difficult.

An ice sheet is a large mass of glacial land ice that covers over 50,000 square kilometers (20,000 square miles). The two ice sheets that now exist on Earth encompass the majority of Greenland and Antarctica. Ice sheets covered much of North America and Scandinavia during the previous ice age.

A new study published in the journal Geology on Thursday rebuilt the progress of one of Greenland’s major tidewater glaciers to better understand long-term glacial dynamics.

“In the news, we’re very used to hearing about glacial retreat, and that’s because in a warming climate scenario which is what we’re in at the moment we generally document ice masses retreating. However, we also want to understand how glaciers react if there is a climate cooling and subsequent advance. To do this, we need to reconstruct glacier geometry from the past,” said Danni Pearce, co-lead author of the study.

The Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets together hold more than 99 percent of the world’s freshwater ice. The Greenland Ice Sheet covers most of the island of Greenland, which is three times the size of Texas, and covers around 1.7 million square kilometers (656,000 square miles).

During a period of cooling when the Norse established settlements in Greenland, an interdisciplinary team of experts studied the progress of Kangiata Nunaata Sermia (KNS), the largest tidewater glacier in southwest Greenland. Tidewater glaciers, unlike glaciers that only exist on land, extend and flow all the way to the ocean or sea, where they can calve and break up into icebergs.

Melt from Greenland not only impacts sea-level change but also the ecology around the ice sheets, fisheries, the biological productivity of the oceans how much algae is growing. And also because the types of glaciers we’re looking at produce icebergs these can cause hazards to shipping and trade, especially if the Northwest Passage opens up as it is expected to.

James Lea

Because glaciers often destroy or alter everything in their path as they advance, reconstructing their progress can be extremely difficult. The research team spent several field seasons in Greenland, walking to isolated locations, many of which had not been visited since the 1930s, in order to unearth the KNS advance record.

“When we went out into the field, we had absolutely no idea whether the evidence would be there or not, so I was incredibly nervous. Though we did a huge amount of planning beforehand until you go out into the field you don’t know what you’re going to find,” said James Lea, the other co-lead author of the study.

The research team was able to inspect and explore locations that would have been missed if they had traveled by helicopter more closely. The team’s foresight paid off, as the sedimentary sequences they analyzed and sampled yielded the information they needed to date and trace the glacier’s progress.

KNS progressed at least 15 km at a rate of ~115 meters per year between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries CE, according to the research team. This pace of advance is equivalent to recent rates of glacial retreat seen over the last ~200 years, demonstrating that glaciers can advance at the same rate as they are retreating now when the temperature is milder.

During the Little Ice Age, the glacier reached its maximum extent in 1761 CE, advancing a total of ~20 kilometers. KNS has retreated ~23 kilometers to its current position since then.

The advance of the glacier corresponded to the Norse presence in Greenland at the time. The researchers discovered that KNS advanced to within 5 kilometers of a Norse farmhouse before reaching its greatest extent during the Little Ice Age.

“Even though KNS was rapidly coming down the fjord, it did not seem to affect the Norse, which we found really unusual,” said Pearce. “So the team started to think about the surrounding environment and the amount of iceberg production in the fjord during that time. At the moment, the fjord is completely filled with icebergs, making boat access challenging, and we know from the historical record that it has been like this for the last 200 years while the glacier has been retreating.”

“However, for KNS to advance at 115 m/yr, it needed to hang onto its ice and could not have been producing a lot of icebergs. So we actually think that the fjord would have looked very different with few icebergs, which allowed the Norse far more easy access to this site for farming, hunting, and fishing.”

Archaeologists who visited the site in the 1930s speculated that circumstances in the fjord must have been different than they are now for the Norse to have occupied the location, and this new research study backs up their theories.

“So we have this counterintuitive notion that climate cooling and glacier advance might have actually helped the Norse in this specific circumstance and allowed them to navigate more of the fjord more easily,” said Lea.

The Norse left Greenland in the fifteenth century CE, and these findings support the theory that a cooling climate was not the reason for their departure; rather, a mix of economic considerations drove the Norse out.

The findings of this study, which reconstruct rapid glacial advances, are also compatible with how ice sheet models work, giving these models’ projections more credibility.

Understanding and preparing for future scenarios of ongoing retreat of the Greenland Ice Sheet and consequent sea-level rise need reliable models and predictions.

“Melt from Greenland not only impacts sea-level change but also the ecology around the ice sheets, fisheries, the biological productivity of the oceans how much algae is growing. And also because the types of glaciers we’re looking at produce icebergs these can cause hazards to shipping and trade, especially if the Northwest Passage opens up as it is expected to,” said James Lea.

Pearce added, “Our research shows that climate cooling can change iceberg calving behavior and drive glacier advance at rates just as rapid as a current retreat. It also shows how resilient the Greenlandic Norse were to the changing environmental conditions. Such adaptation can give us hope for the changes we may face over the coming century.”