Down syndrome, which affects one in every 700 births, is the most prevalent birth condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Traditional non-invasive prenatal tests, however, are unreliable or dangerous for both the mother and the fetus.

Researchers have now created a sensitive new biosensor that may one day be used to identify DNA associated with fetal Down syndrome in the blood of pregnant women. The ACS journal Nano Letters is where they publish their findings.

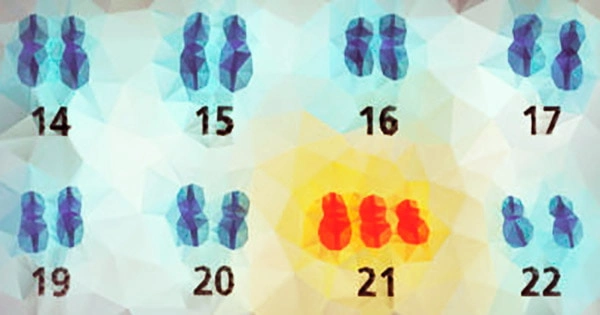

A second whole or partial copy of chromosome 21 is produced as a result of faulty cell division, which results in the genetic condition known as Down syndrome. Down syndrome’s physical characteristics and developmental abnormalities are brought on by this excess genetic material.

Down syndrome is a genetic condition brought on by the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21, and it is characterized by varying degrees of intellectual and developmental issues. Pregnant women can have ultrasound scans or indirect blood biomarker testing to screen for the disease, although misdiagnosis rates are substantial.

Individuals with Down syndrome may have varying degrees of intellectual disability and developmental delays. It is the most prevalent genetic chromosomal defect and the root of children’s learning problems. It frequently results in other medical issues as well, such as cardiac and gastrointestinal problems.

A conclusive diagnosis is provided by amniocentesis, a surgery in which doctors put a needle into the uterus to collect amniotic fluid. However, the procedure is risky for both the pregnant mother and the fetus. Although whole-genome sequencing is a new technique, it is still a slow and expensive procedure.

The goal of Zhiyong Zhang and colleagues was to create a quick, accurate, and affordable test that could identify high levels of chromosome 21 DNA in pregnant women’s blood.

The researchers employed molybdenum disulfide single-layer field-effect transistor biosensor devices. To the surface, they applied gold nanoparticles. They mounted probe DNA sequences that can detect a certain sequence from chromosome 21 on the nanoparticles.

Chromosome 21 DNA fragments were attached to the sensor’s probes when the team introduced them, reducing the sensor’s electrical current. The biosensor was far more sensitive than other reported field-effect transistor DNA sensors, being able to detect DNA concentrations as low as 0.1 fM/L.

In the future, the test, according to the researchers, might be used to compare blood levels of chromosome 21 DNA with those of another chromosome, such 13, to see whether there are any extra copies that might indicate a fetus has Down syndrome.