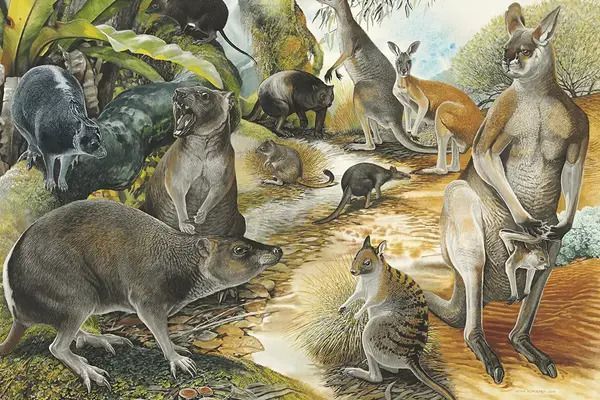

Palaeontologists at Flinders University have described three strange new species of huge fossil kangaroos from Australia and New Guinea, revealing that they are more diversified in shape, range, and hopping style than previously assumed. The three new species are from the extinct genus Protemnodon, which lived between 5 million and 40,000 years ago, with one roughly double the size of the largest red kangaroo alive today.

The study followed the finding of several full fossil kangaroo skeletons in Lake Callabonna, arid South Australia, in 2013, 2018, and 2019. These exceptional fossils enabled lead researcher Dr Isaac Kerr, then a PhD student, to solve a nearly 150-year-old conundrum about the species of Protemnodon.

The latest Flinders University study examined all Protemnodon species and discovered significant differences among them. The species evolved to live in various settings and even hopped in varied ways.

Protemnodon would have resembled a grey kangaroo, but was generally more squat and strong. While some species were around 50 kg, others were significantly larger than any surviving kangaroo. However, one new species discovered as part of the newest study, Protemnodon viator, was far larger, weighing up to 170 kg. This is approximately twice as much as the largest male red kangaroo.

Our study suggests that this is true of only three or four species of Protemnodon, which may have moved something like a quokka or potoroo — that is bounding on four legs at times, and hopping on two legs at others.

Dr Isaac Kerr

Protemnodon viator was well-adapted to its dry central Australian habitat, dwelling in places comparable to where red kangaroos live now. It was a kangaroo with long legs that hopped rapidly and efficiently. Viator is a Latin word that means ‘traveller’ or ‘wayfarer’.

The Australian researchers identified two other new species, Protemnodon mamkurra and Protemnodon dawsonae, while also examining the work of earlier researchers, notably British naturalist Sir Richard Owen, who originated the word ‘dinosaur’ in Victorian England.

Owen, a British palaeontologist, described the first Protemnodon species in 1874, focusing mostly on fossil teeth, which was the typical practice at the time. He discovered minor changes in his specimens’ teeth and identified six Protemnodon species.

Successive studies have whittled away at some of these early descriptions, however the new Flinders University study agrees with one of his species, Protemnodon anak. This first specimen described, called the holotype, still resides in the Natural History Museum in London.

Dr Kerr says it previously was suggested that some or all Protemnodon were quadrupedal. “However, our study suggests that this is true of only three or four species of Protemnodon, which may have moved something like a quokka or potoroo — that is bounding on four legs at times, and hopping on two legs at others. The newly described Protemnodon mamkurra is likely one of these. A large but thick-boned and robust kangaroo, it was probably fairly slow-moving and inefficient. It may have hopped only rarely, perhaps just when startled.”

According to Dr Kerr, the greatest fossils of this species can be found in Green Waterhole Cave in southeastern South Australia, on the Boandik people’s property. Boandik elders and language experts from the Burrandies Corporation decided the species’ name, mamkurra. It translates to ‘great kangaroo’.

It is remarkable for a single genus of kangaroo to live in such diverse settings, he says. “For example, the different species of Protemnodon are now known to have inhabited a broad range of habitats, from arid central Australia into the high-rainfall, forested mountains of Tasmania and New Guinea.”

The third of the new species, Protemnodon dawsonae, is known from fewer fossils than the other two, and is more of a mystery. It was most likely a mid-speed hopper, something like a swamp wallaby. It was name in honour of the research work of Australian palaeontologist Dr Lyndall Dawson, who studied kangaroo systematics and the fossil material from ‘Big Sink’, the part of the Wellington Caves in NSW, from which the species is mostly known.

To gather data for the study, Dr Kerr visited the collections of 14 museums in four countries and studied “just about every piece of Protemnodon there is.”

“We photographed and 3D-scanned over 800 specimens collected from all over Australia and New Guinea, taking measurements, comparing and describing them. It was quite the undertaking. It feels so good to finally have it out in the world, after five years of research, 261 pages and more than 100,000 words. I really hope that it helps more studies of Protemnodon happen, so we can find out more of what these kangaroos were doing. Living kangaroos are already such remarkable animals, so it’s amazing to think what these peculiar giant kangaroos could have been getting up to.”

While Protemnodon fossils are extremely frequent in Australia, they have traditionally been discovered ‘isolated’, or as individual bones without the rest of the animal. This has previously impeded palaeontologists’ studies of Protemnodon, making it difficult to determine how many species existed, how to distinguish between them, and how the species differed in size, geographic range, locomotion, and adaptations to their natural surroundings.

Protemnodon had become extinct on mainland Australia by 40,000 years ago, however it may have survived in New Guinea and Tasmania for a bit longer. This extinction happened despite differences in size, adaptability, environment, and geographic distribution. Many closely related animals, such as wallaroos and gray kangaroos, did not experience the same fate for unknown reasons. This question may soon be answered by further research aided in some part by this study.

“It’s great to have some clarity on the identities of the species of Protemnodon,” says Flinders Professor Gavin Prideaux, a co-author of the major new article in Megataxa. “The fossils of this genus are widespread and they’re found regularly, but more often than not you have no way of being certain which species you’re looking at. This study may help researchers feel more confident when working with Protemnodon.”