Dynamic fractal scaling refers to the idea that certain properties of a system may exhibit self-similarity over a range of scales, and can be described using a power law. This type of behavior has been observed in a variety of systems, including magnetic crystals.

In the context of magnetic crystals, dynamic fractal scaling may be observed in the behavior of the magnetic moments, or “spins,” within the crystal. This behavior can be influenced by various factors, such as the interactions between the spins, the presence of defects in the crystal, and external stimuli such as temperature and applied magnetic fields. The study of dynamic fractal scaling in magnetic crystals and other systems can be an active area of research, as it can provide insights into the underlying mechanisms and behaviors of these systems.

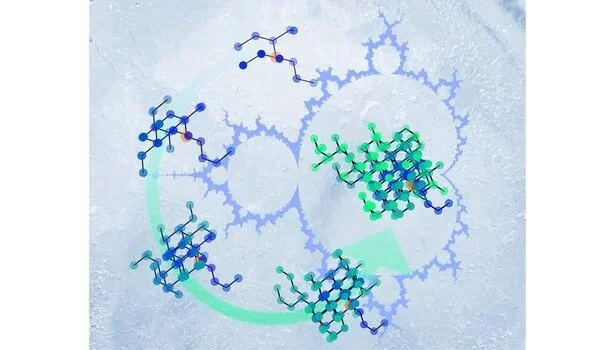

Researchers discovered an entirely new type of fractal in a class of magnets known as spin ices. The discovery was surprising because the fractals were discovered in a clean three-dimensional crystal, which was not expected. Even more remarkable, the fractals are visible in the crystal’s dynamical properties but hidden in its static ones. These characteristics inspired the term ’emergent dynamical fractal’.

Dimension has a strong influence on the nature and properties of materials. Consider how different life would be in a one-dimensional or two-dimensional world compared to the three dimensions we’re used to. With this in mind, it’s not surprising that fractals, or objects with fractional dimensions, have gotten a lot of attention since their discovery. Despite their apparent strangeness, fractals appear in unexpected places, such as snowflakes and lightning strikes, as well as natural coastlines.

The fact that the fractals are dynamical meant they did not show up in standard thermal and neutron scattering measurements. It was only because the noise was measuring the monopoles motion that it was finally spotted.

Grigera and Tennant

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems in Dresden, the University of Tennessee, and the Universidad Nacional de La Plata discovered a completely new type of fractal in a class of magnets known as spin ices. The discovery was surprising because the fractals were discovered in a clean three-dimensional crystal, which was not expected. Even more remarkable, the fractals are visible in the crystal’s dynamical properties but hidden in its static ones. These characteristics inspired the term “emergent dynamical fractal.”

The fractals were discovered in crystals of the material dysprosium titanate, where the electron spins behave like tiny bar magnets. These spins cooperate through ice rules that mimic the constraints that protons experience in water ice. For dysprosium titanate, this leads to very special properties.

Jonathan Hallén of the University of Cambridge is a Ph.D. student and the lead author on the study. He explains that “at temperatures just slightly above absolute zero the crystal spins form a magnetic fluid.” This is no ordinary fluid, however.

“With tiny amounts of heat the ice rules get broken in a small number of sites and their north and south poles, making up the flipped spin, separate from each other traveling as independent magnetic monopoles.”

The motion of these magnetic monopoles led to the discovery here. As Professor Claudio Castelnovo, also from the University of Cambridge, points out: “We knew there was something really strange going on. Results from 30 years of experiments didn’t add up.”

Referring to a new study on the magnetic noise from the monopoles published earlier this year, Castelnovo continued, “After several failed attempts to explain the noise results, we finally had a eureka moment, realizing that the monopoles must be living in a fractal world and not moving freely in three dimensions, as had always been assumed.”

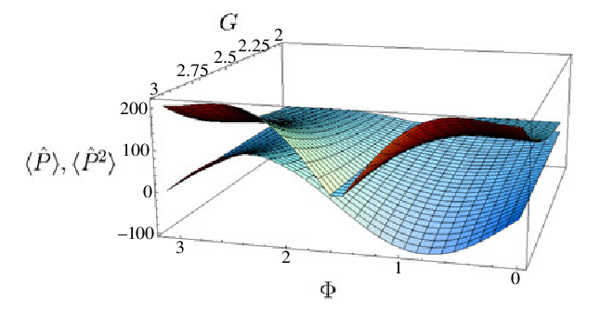

In fact, this latest analysis of the magnetic noise showed the monopole’s world needed to look less than three-dimensional, or rather 2.53 dimensional to be precise! Professor Roderich Moessner, Director of the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems in Germany, and Castelnovo proposed that the quantum tunneling of the spins themselves could depend on what the neighboring spins were doing.

As Hallén explained, “When we fed this into our models, fractals immediately emerged. The configurations of the spins were creating a network that the monopoles had to move on. The network was branching as a fractal with exactly the right dimension.”

But why had this been missed for so long? Hallén elaborated that, “this wasn’t the kind of static fractal we normally think of. Instead, at longer times the motion of the monopoles would actually erase and rewrite the fractal.”

This made the fractal invisible to many conventional experimental techniques. Working closely with Professors Santiago Grigera of the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, and Alan Tennant of the University of Tennessee, the researchers succeeded in unravelling the meaning of the previous experimental works.

“The fact that the fractals are dynamical meant they did not show up in standard thermal and neutron scattering measurements,” said Grigera and Tennant. “It was only because the noise was measuring the monopoles motion that it was finally spotted.”

As regards the significance of the results, which appear in Science this week, Moessner explains: “Besides explaining several puzzling experimental results that have been challenging us for a long time, the discovery of a mechanism for the emergence of a new type of fractal has led to an entirely unexpected route for an unconventional motion to take place in three dimensions.”

Overall, the researchers are interested to see what other properties of these materials may be predicted or explained in light of the new understanding provided by their work, including ties to intriguing properties like topology. With spin ice being one of the most accessible instances of a topological magnet, Moessner said, “the capacity of spin ice to exhibit such striking phenomena makes us hopeful that it holds the promise of further surprising discoveries in the cooperative dynamics of even simple topological many-body systems.”