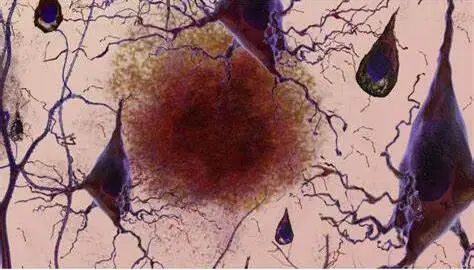

While Alzheimer’s disease generally affects cognition and memory, it is rarely associated with unusual visual symptoms. Visual abnormalities or hallucinations can occur in some people with advanced Alzheimer’s disease, although they are not considered a definitive symptom of the disease.

A group of international researchers, led by UC San Francisco, has conducted the first large-scale study of posterior cortical atrophy, a perplexing constellation of visuospatial symptoms that appear as the early signs of Alzheimer’s disease. These symptoms appear in up to 10% of Alzheimer’s patients. The study collected data from over 1,000 patients at 36 sites across 16 nations. It is published in the Lancet Neurology.

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) overwhelmingly predicts Alzheimer’s, the researchers found. Some 94% of the PCA patients had Alzheimer’s pathology and the remaining 6% had conditions like Lewy body disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. In contrast, other studies show that 70% of patients with memory loss have Alzheimer’s pathology.

We need more awareness of PCA so that it can be flagged by clinicians. Most patients see their optometrist when they start experiencing visual symptoms and may be referred to an ophthalmologist who may also fail to recognize PCA. We need better tools in clinical settings to identify these patients early on and get them treatment.

Marianne Chapleau

Patients with PCA, unlike those with memory problems, have difficulty judging distances, distinguishing between moving and stationary objects, and completing tasks such as writing and retrieving a dropped item, according to co-first author Marianne Chapleau, Ph.D., of the UCSF Department of Neurology, the Memory and Aging Center, and the Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

According to the researchers’ findings, most patients with PCA have normal cognition early on, but by the time of their first diagnostic visit, which occurs an average of 3.8 years after symptom onset, mild or moderate dementia has developed, with deficits identified in memory, executive function, behavior, and speech and language.

At the time of diagnosis, 61% demonstrated “constructional dyspraxia,” an inability to copy or construct basic diagrams or figures; 49% had “space perception deficit,” difficulties identifying the location of something they saw; and 48% had “simultanagnosia,” an inability to visually perceive more than one object at a time. Additionally, 47% faced new challenges with basic math calculations and 43% with reading.

We need better tools and training to identify patients

“We need more awareness of PCA so that it can be flagged by clinicians,” Chapleau added. “Most patients see their optometrist when they start experiencing visual symptoms and may be referred to an ophthalmologist who may also fail to recognize PCA,” she went on to say. “We need better tools in clinical settings to identify these patients early on and get them treatment.”

PCA has an average age of symptom start of 59, which is several years younger than conventional Alzheimer’s. This is yet another reason why PCA sufferers are underdiagnosed, according to Chapleau.

Early identification of PCA may have important implications for Alzheimer’s treatment, said co-first author Renaud La Joie, Ph.D., also of the UCSF Department of Neurology and the Memory and Aging Center. In the study, levels of amyloid and tau, identified in cerebrospinal fluid and imaging, as well as autopsy data, matched those found in typical Alzheimer’s cases. As a result, patients with PCA may be candidates for anti-amyloid therapies, like lecanemab (Leqembi), approved by the U.S Food and Drug Administration in January 2023, and anti-tau therapies, currently in clinical trials, both of which are believed to be more effective in the earliest phases of the disease, he said.

“Patients with PCA have more tau pathology in the posterior parts of the brain, involved in the processing of visuospatial information, compared to those with other presentations of Alzheimer’s. This might make them better suited to anti-tau therapies,” he said.

Patients have mostly been excluded from trials, since they are “usually aimed at patients with amnestic Alzheimer’s with low scores on memory tests,” La Joie added. “However, at UCSF we are considering treatments for patients with PCA and other non-amnestic variants.”

Better understanding of PCA is “crucial for advancing both patient care and understanding the processes that drive Alzheimer’s disease,” according to senior author Gil Rabinovici, M.D., head of the UCSF Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. “Doctors must learn to detect the syndrome so that patients can receive the proper diagnosis, counseling, and care.

“From a scientific standpoint, we need to understand why Alzheimer’s disease specifically targets visual rather than memory parts of the brain. Our study discovered that 60% of PCA patients were women; greater understanding of why they appear to be more vulnerable is an essential topic of future research.”