Creating a hedging strategy for coral restoration that balances diversity and ecosystem benefits requires taking into account a variety of factors and incorporating both ecological and financial concerns.

An international team of researchers devised a novel new strategy for selecting a subset of key coral species that will best preserve ecosystem functions critical to reef health. Their hedging strategy provides a simple framework for restoration practitioners to use when selecting target species for projects based on spatial scale and resources.

A novel approach to selecting coral species for reef restoration has been presented to resource managers and conservationists. During a workshop organised by the University of Melbourne (U Melbourne) and the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), an international team of scientists collaborated to develop this approach. This international team of scientists, led by a University of Hawai’i (UH) at Manoa researcher, revealed a strategy for selecting a set of key coral species that will best maintain ecosystem functions critical to reef health in a study published today in the Journal of Applied Ecology.

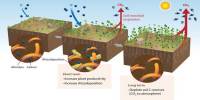

The ecosystem services that coral reefs provide for people, such as coastal protection and fisheries, rely on coral species with a wide range of what are known as life history strategies, such as slow to fast growing, mounding to branching shapes, and under to upper storey.

Joshua Madin

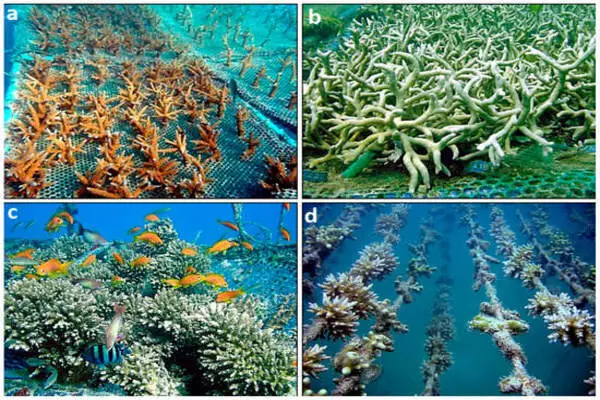

Coral reefs are rapidly disappearing around the world as a result of a variety of anthropogenic disturbances, with global warming being the most serious threat. Coral reef restoration is a growing research field and industry in response. Most coral reefs are made up of tens to hundreds of different stony coral species, but resources for coral reef restoration are insufficient to restore them all. There are currently no methods for selecting species that will best preserve species diversity and ecosystem function.

“The ecosystem services that coral reefs provide for people, such as coastal protection and fisheries, rely on coral species with a wide range of what are known as life history strategies, such as slow to fast-growing, mounding to branching shapes, and under to upper storey,” said Joshua Madin, study lead author and research professor at the UH Manoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST). “As a result, when restoring coral reefs, restoration practitioners must consider this range of local species, just as forest restoration requires more than just fast-growing plants.”

The research team combined databases of coral species traits with their ecological characteristics, including their resistance to thermal bleaching, to see how best to select sets of species for restoration using a hedging approach, much like that used for investment portfolios.

“Selection based on ecological characteristics is important for hedging against future species loss, whereas trait diversity is important for hedging against the loss of certain ecosystem services, reef-building groups, life history categories, and evolutionary variety,” said Madin.

This hedging strategy provides a straightforward framework for restoration practitioners to use when selecting target species for their projects based on spatial scale and resources.

“For example, if a programme only has funds to focus on 20 coral species, they would want to focus on the sets of species to get the most ecosystem bang for their buck,” said senior author Professor Madeleine van Oppen of U Melbourne and AIMS. “Currently, coral restoration programmes tend to focus on easy-to-collect, “weedy” coral species, which have similar characteristics and cannot support ecosystem services on their own.”

The study also found that, if species data are limited, selecting species at random is much better than selecting species that are easy to collect. The extra effort required will pay off in terms of preserving ecosystem services that communities rely on. The method can be applied to any coral reef for which coral trait data are available.

Coral restoration is a major focus of research and development as coral reefs face greater threats, particularly in Hawaii and Australia, where people rely on reefs for tourism, recreation, coastal protection, and sustenance. The new method of coral species selection is already being used in a hybrid reef programme in Hawai’i funded by the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency. The groundbreaking project’s goal is to build an engineered structure that will provide a habitat for corals and other reef life while protecting coastlines from flooding, erosion, and storm damage.