Consumer surplus also referred to as the surplus of the customer, is an economic indicator of consumer benefits. It is the difference between a consumer’s target price that they are willing to pay and the true price they pay. It is determined by measuring the difference, also known as the equilibrium price, between the willingness of the buyer to pay for a commodity and the actual price they pay. On the off chance that a purchaser is happy to pay more for a unit of a decent than the current asking value, they are getting more profit by the bought item than they would if the cost was their most extreme eagerness to pay.

A consumer surplus happens when the demand is willing to pay more than the existing market price for a given commodity. The economic theory of marginal utility, which is the additional gratification that an individual derives from purchasing one more unit of a product or service, is based on consumer surplus. To quantify the social benefits of public goods such as national highways, canals, and bridges, the idea of consumer surplus was established in 1844. It has been a significant instrument in the field of government assistance financial matters and the detailing of assessment arrangements by governments.

Drinking water is an example of a good that usually has a strong consumer surplus. People, since they need it to survive, would pay very high prices for drinking water. If they had to, the difference between the price they would pay, and the amount they are paying today, is their market surplus. The usefulness of the first few liters of drinking water (as it prevents death) is very high because the first few liters are likely to have a higher consumer surplus than the next few liters.

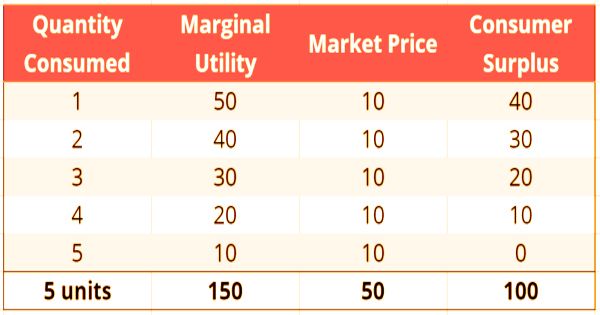

Consumer surplus depends on the monetary hypothesis of negligible utility, which is the extra fulfillment a shopper gains from one more unit of a decent or administration. The fulfillment shifts by the purchaser, because of contrasts in close to home inclinations. In principle, because of the declining marginal utility extracted from the commodity, the more of a commodity a customer owns, the less likely he/she is to pay more for the product. Based on their personal choice, the utility a good or service offers varies from individual to individual.

Calculating Consumer Surplus:

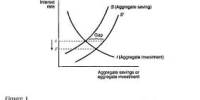

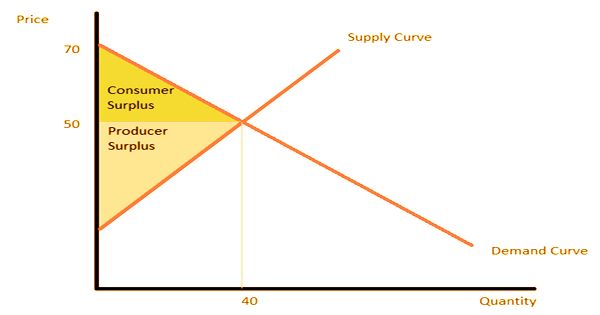

Usually, because of the declining marginal utility or added value they get, the more of a product or service that customers have, the less they are willing to invest more of it. The point where supply and demand meets is the price of equilibrium. The area above the supply level and below the equilibrium price is called the product surplus (PS), and the consumer surplus (CS) is the area below the level of demand and above the equilibrium price.

The most extreme sum a shopper would pay for a given amount of a decent is the whole of the greatest value they would pay for the primary unit, the (lower) greatest value they would pay for the subsequent unit, and so forth. The formula for market surplus is CS = ½ (base) (height) when taking the demand and supply curves into consideration. The relationship between the price of the product and the quantity of the product requested at that price is shown, with the price being drawn on the y-axis of the graph and the quantity requested being drawn on the x-axis. The demand curve is sloping downward because of the law of decreasing marginal utility.

Consumer surplus for an item is zero when the interest for the item is totally flexible. This is on the grounds that buyers are happy to coordinate the cost of the item. Normally these costs are diminishing; they are given by the individual interest bend, which must be produced by a reasonable customer who augments utility subject to a spending limitation. When demand is completely inelastic, the market surplus is infinite since the demand is not influenced by a change in the price of the commodity. This includes items such as milk, water, etc, which are essential necessities.

Consumer surplus for an item is zero when the interest for the item is totally flexible. This is on the grounds that buyers are happy to coordinate the cost of the item. Normally these costs are diminishing; they are given by the individual interest bend, which must be produced by a reasonable customer who augments utility subject to a spending limitation. Decreasing marginal utility means that from an additional unit, an individual receives less additional utility. According to economist Alfred Marshall, “the more you consume a certain commodity, the lower the satisfaction derived from each additional unit of consumption.”

According to Alfred Marshal: Consumer Surplus = Total Utility – (Price x Quantity)

Example of Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus first demonstrated by Willig (1976), can be used as a social welfare calculation. It can provide an estimate of improvements in welfare with a uniform price adjustment. As the price of a good falls and decreases as the price of a good grows, the market surplus still increases. However, with frequent shifts in price and/or sales, the consumer surplus cannot be used to approximate economic welfare since it is no longer single-valued. Companies, however, know how to turn customer surplus into, or for their benefit, producer surplus.

Information Sources: