According to new research, the idea that the COVID-19 epidemic was a hoax, that its severity was overstated, or that the virus was purposefully disseminated for evil purposes serves as a “gateway” to the idea that conspiracy theories in general are true.

People who expressed a stronger level of trust in the pandemic conspiracy theories for which there is no proof were more likely to later express a conviction that Donald Trump’s victory in the 2020 presidential election had been stolen by massive voting fraud, which is likewise untrue. Additionally, those who claimed to think COVID-19 was a fake showed a greater overall propensity to believe in conspiracy theories.

Based on the results, the Ohio State University researchers have proposed the “gateway conspiracy” hypothesis, which argues that conspiracy theory beliefs prompted by a single event lead to increases in conspiratorial thinking over time.

Preliminary evidence suggests a sense of distrust may function as one trigger.

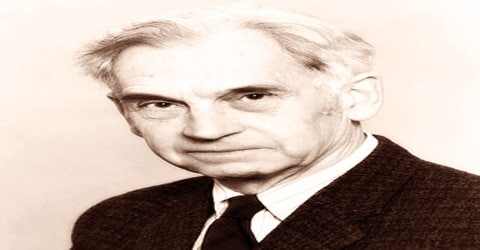

“It’s speculative, but it appears that once people adopt one conspiracy belief, it promotes distrust in institutions more generally it could be government, science, the media, whatever,” said senior author Russell Fazio, professor of psychology at Ohio State. “Once you start viewing events through that distrustful lens, it’s very easy to adopt additional conspiracy theories.”

The study is published today in the journal PLOS ONE.

Since the study of conspiracy theories is still relatively new, researchers have tended to look for characteristics that can be used to predict a person’s propensity to believe in conspiracies at a certain period.

“But if you read interviews or forums frequented by conspiracy theorists, you see a phenomenon where people tend to go down the rabbit hole after something happens in their life that triggers general interest in conspiracy theories,” said first author Javier Granados Samayoa, who completed the work while a graduate student in psychology at Ohio State. “With COVID-19, there was this large event that people could not control, so how could they make sense of it? One way is by adhering to conspiracy theories.”

It’s speculative, but it appears that once people adopt one conspiracy belief, it promotes distrust in institutions more generally it could be government, science, the media, whatever. Once you start viewing events through that distrustful lens, it’s very easy to adopt additional conspiracy theories.

Professor Russell Fazio

The researchers asked 501 participants in a June 2020 survey to answer questions assessing their beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories, political ideology and what is called conspiracist ideation, or one’s overall affinity for conspiracy theories.

In this section, participants used a 5-point scale ranging from “definitely not true” to “definitely true” to rate statements such as “Some UFO sightings and rumors are planned or staged in order to distract the public from real alien contact” and “New and advanced technology which would harm current industry is being suppressed.”

Six months later, in December 2020, 107 of those same participants again responded to statements gauging their level of conspiratorial thinking. By having participants rate how strongly they thought there had been widespread voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election, researchers were able to gauge conspiracist thinking.

Statistical analysis showed that participants who reported greater belief that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was released for dark purposes and that the severity of COVID-19 disease was blown out of proportion also reported greater belief that the 2020 election had been stolen from Trump. And compared to their baseline conspiracist ideation measured in the June survey, COVID skeptics had higher levels of general endorsement of conspiracy theories six months later.

“The association held true even after the analysis took into account the association between belief in conspiracy theories about COVID-19 and voter fraud and conservative political views,” said Granados Samayoa, now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania.

The team also cited data from a large United Kingdom multi-part survey conducted during the early spring and late fall of 2020 that supported the gateway conspiracy hypothesis: The Ohio State team’s analysis showed that belief among a nationally representative sample of UK adults that the pandemic was a hoax predicted increases in conspiracist ideation over time.

One notable tendency in the Ohio State data suggested that even among people who initially had modest levels of conspiracist ideation, financial hardship during the lockdown may have contributed to the development of conspiracy theories regarding the epidemic.

“And then there is the question: Once that happens, what changes over time? That’s where we got into this longitudinal work, which has been absent in previous research,” Fazio said.

This study concentrated on views that are not backed by evidence and are refuted by the evidence that is there, even though certain historical conspiracy theories have shown to be true. The researchers noted that a deeper comprehension of the mechanisms underlying conspiratorial thinking could aid in halting the spread of conspiracist ideas, which are linked to a higher risk of violence, discrimination, and unhealthy lifestyle choices, among other detrimental effects on both the individual and the larger society.

“These findings show that we need to be prepared for any additional large-scale events similar to COVID-19 to stem off conspiracist ideation because once people go down the rabbit hole, they may get stuck,” Granados Samayoa said.