Climate change has the potential to alter the human-raptor relationship in a number of ways. Raptors, or birds of prey, are highly adapted to their environments and the food chains that sustain them. As climate patterns change, it can disrupt these delicate balances, leading to changes in raptor behavior and distribution.

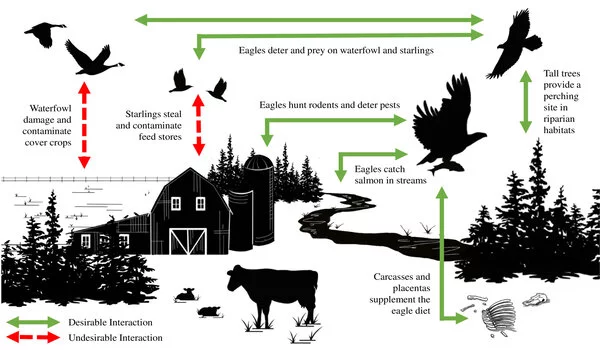

In parts of northwestern Washington State, bald eagles and dairy farmers coexist in a mutually beneficial relationship. This “win-win” relationship, according to a new study, is a more recent development, driven by the impact of climate change on eagles’ traditional winter diet of salmon carcasses, as well as increased eagle abundance as a result of decades of conservation efforts. The findings were published in the journal Ecosphere.

“The narrative around birds of prey and farmers has traditionally been negative and combative, primarily due to claims of livestock predation,” said lead author Ethan Duvall of Cornell University’s Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology. “Dairy farmers in northwestern Washington, on the other hand, do not see eagles as a threat. Indeed, many farmers value the services provided by eagles, such as carcass removal and pest deterrence.”

Climate change has altered the chum salmon spawning schedule, causing them to run earlier in the winter. Now the salmon are spawning when the annual Nooksack River flooding is at its peak. The fish that spawn and die are swept away by the high water instead of being deposited on shore where the eagles can easily access them.

Ethan Duvall

Duvall conducted face-to-face interviews with farmers on small, medium, and large dairy operations in Whatcom County with collaborators Emily Schwabe and Karen Steensma from the University of Washington and Trinity Western University in Canada to better understand this unique relationship. The study was inspired by Duvall’s recent findings that eagles were relocating from rivers to farmland in response to the declining availability of salmon carcasses over the last 50 years.

“Climate change has altered the chum salmon spawning schedule, causing them to run earlier in the winter,” said Duvall. “Now the salmon are spawning when annual Nooksack River flooding is at its peak. The fish who spawn and die are swept away by the high water instead of being deposited on shore where the eagles can easily access them.”

Duvall points out that the timing change has reduced the number of available carcasses on the local river, but not the number of individual salmon. However, many rivers in the Pacific Northwest have seen dramatic declines in salmon populations, reducing winter resources for eagles.

To compensate for the decrease in their natural food supply, eagles have turned to a steady stream of dairy farm byproducts resulting from cow births and deaths, as well as prey on waterfowl populations that feed and rest in agricultural areas. Bald Eagles also keep traditional farm pests like rodents and starlings at bay.

“We know this positive interaction between farmers and Bald Eagles is not the norm in many other agricultural areas, especially near free-range poultry farms where the eagles snatch chickens,” said Duvall. “But this study gives me hope that moving forward, farmers, wildlife managers, and conservationists can come together to think critically about how to maximize benefits for people and wildlife in the spaces they share.”

Overall, the effects of climate change on raptors and their relationships with humans are complex and varied. However, as with many other aspects of climate change, it is clear that there is a need for ongoing research and monitoring to better understand these impacts and develop strategies for mitigating them.