Garden seed, chicken coops, and rabbit cages were all sold out by 2020. Now we know how much protein can be grown in people’s backyards. Many people are concerned about what they will eat for protein if supply chains are interrupted in 2020 due to meat shortages. Gathering eggs, rearing animals, and cultivating their own food became popular among some individuals.

The labor is well worth it, according to a team from Michigan Technological University and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The researchers looked at how a normal family with a typical backyard might produce chickens, rabbits, or soybeans to fulfill their protein needs in a recent study published in Sustainability.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI), Americans consume a lot of protein, with the average individual requiring 51 grams per day. This equates to 18,615 grams per year or 48,399 grams per year for a 2.6-person family. Burgers are popular in the United States, but few individuals have the space to grow a steer next to their garage, and most local regulations tremble at the very mention of a renegade cowpie.

Small animals, on the other hand, are more effective protein providers and are frequently permitted inside city borders. The usual backyard is 800 to 1,000 square meters (about 8,600 to 10,700 square feet) in size.

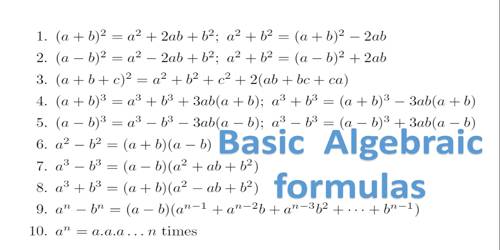

Amino acids are the building components that make up proteins. There are roughly 20 distinct amino acids that may be linked together in various ways. They’re used by our bodies to build new proteins like muscle and bone, as well as other substances like enzymes and hormones. It may also utilize them as a source of energy.

“You don’t have to convert your entire backyard into a soybean farm. A little goes a long way,” said Joshua Pearce, one of the study co-authors and Michigan Tech’s Richard Witte Endowed Professor of Materials Science and Engineering and professor of electrical and computer engineering. “I’m a solar engineer; I look at surface area and think of photovoltaic production. Many people don’t do that they don’t treat their backyards as a resource. They can really be a time and money drain if they have to mow and fertilize them. When we handle our yards as an asset, though, we may become rather self-sufficient.”

Theresa Meyer and Alexis Pascaris of Michigan Tech, as well as David Denkenberger of the University of Alaska, are among Pearce’s multidisciplinary co-authors. The lab joined together to do an agrovoltaics study to see how well rabbits could be raised beneath solar panels.

However, when they went to buy cages in spring 2020, they realized that animal equipment and home garden supplies were in limited supply across the country. The group, like many others, shifted and refocused its efforts to combat the pandemic’s effects.

They discovered that raising chickens or rabbits in the backyard might balance protein intake by up to 50%. Buying feed and rearing 52 chickens or 107 rabbits was necessary to provide the complete protein demand using animals and eggs. Of course, that’s more than most local regulations allow, and rearing a creature isn’t as easy as setting up a planting box. While pasture-raised rabbits maintain your yard, Pearce claims that the “real winner is soy.”

A protein’s nutritional value is determined by the number of essential amino acids it contains. Essential amino acids are found in varying quantities in various diets. Generally:

- Animal products (such as chicken, beef or fish, and dairy products) have all of the essential amino acids and are known as ‘complete protein (or ideal or high-quality protein).

- Soy products, quinoa, and the seed of a leafy green called amaranth (consumed in Asia and the Mediterranean) also have all of the essential amino acids.

- Plant proteins (beans, lentils, nuts, and whole grains) usually lack at least one of the essential amino acids and are considered ‘incomplete’ proteins.

It is considerably more effective to consume plant protein directly than feeding it to animals first. Soy may provide 80 percent to 160 percent of a household’s protein needs, and when cooked as edamame, it’s like “high-protein popcorn.” Savings are feasible when food costs rise, according to the team’s economic studies, but savings are dependent on how individuals value food quality and personal effort.

“It does take time. And if you have the time, it’s a good investment,” Pearce said, pointing to other research on building community with gardens, mental health benefits of being outside, and simply a deeper appreciation for home-raised food.

“Our research revealed that many Americans might engage in dispersed food production, making the United States more sustainable and robust to supply chain shocks.”