Executive Summary

In our country there are lots of organizations performed in the field of social activities and by increased their profit earning ratio, among them the Dutch-Bangla Bank is best performing in this field. So we have selected of this organization to conduct our correlation. We have taken some data as like profit earning ratio from 2001 – 2004, net profit data from 2001 – 2004, dividend per share and expenditure of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited, which is expensed for the corporate social responsibility. We have to find out the relationship between the corporate social responsibility and its influence on share price. Here, we need to construct 4 types of data table, we also focuses some literature review and history of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited and its social activities. Here, we need to assign some numerals values that we discussed in our limitations.

Problem Statement

Maintenance of environmental standards is a very important issue in today’s business world. Companies, which are environmentally, concern to show the better performance in the profit earning ability. As performances in the share market largely depend on the profit earning ability. The highest performing ability will achieve the higher rate of profit. Management of the companies wants to find out weather there is a significant relationship between environmental reporting and their performance in the share price.

Objective of the Study

The purpose of this study is to find out the environmental reporting and its influence of share price. Actually we will study the level of environmental concern and activities of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited and its influence of share price and its relationship of international market price of share.

Here, we also find out the correlation between the social activities and its influence on share price.

Literature Review

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies Survey: corporate social responsibility

The union of concerned executives Jan 20th 2005 From The Economist print edition CSR as practiced means many different things.On the face of it, questioning the efforts of companies to behave responsibly is an odd thing to do—unless you are accusing them of faking it, or of falling below some commonly agreed minimum standard. How could a company ever behave too responsibly? The very term “corporate social responsibility” endorses the actions to which it is applied. No doubt that is why companies fasten the label to a quite bewildering variety of supposedly enlightened, progressive or charitable corporate actions.

At one end of the broad span of CSR lie corporate policies that any well-run company ought to have in place anyway, policies that are called for on any sensible view of business ethics or good management practice. These include not lying to your employees, for instance, not paying bribes, and looking farther ahead than the next few weeks. At the other end of the range are the more ambitious and distinctive policies that differentiate between leaders and laggards in the CSR race—large expenditures of time and resources on charitable activities, for instance, or binding commitments to “ethical investment”, or spending on environmental protection beyond what regulators demand.

In other words, at the mild end of the range are practices that do not need any special CSR defense: they can perfectly well justify themselves in simpler ways, either as meeting standards of ordinary decency (of which more later), or as being necessary in any case if managers are to run a successful business. The issue here is not whether the activities themselves make sense, but whether they deserve to be dignified by the term “corporate social responsibility”—that is, whether they deserve the special praise which this label is intended to elicit.

At the strong end of the range, many activities do deserve a special label: they go well beyond the requirements of ordinary decency or business necessity, so the term CSR is serving a useful purpose. But can the same be said of the policies?

At first sight that looks like a churlish question. What could possibly be wrong with policies such as corporate charity or careful attention to the demands of environmental protection and sustainable development? Sometimes nothing, but it depends. Many individual acts of good corporate citizenship do make sense in business terms, or as ways of advancing the public good, or both. But others do not.

Sometimes CSR policies are motivated by genuine concern for the intended beneficiaries, or by a conscientious belief that businesses must earn their “licence to operate”. There are some kindly CEOs out there, and some with a troubled conscience. But there can be other motives for CSR too. There are quite a few vain CEOs who enjoy the attention which CSR leadership brings them, and many others who, having climbed their way to the top, seem to find running a profitable company too small a test of their talents. Yet whatever the variations, one thing is constant: the weight given to specious arguments about what businesses must do to justify their existence and pay their way in society.

Putting those arguments about the duties of business to one side for the moment, setting motives aside as well and thinking only of results, one might ask two questions of any act of supposedly enlightened corporate citizenship. Does it improve the company’s long-term profitability? And does it advance the broader public good?

Two tests Successful managers usually do both at once, of course: merely by running a profitable company, they are likely to be advancing the public good as well. This argument will be taken up in more detail below. Some of the business practices that are often (perhaps misleadingly) labelled as CSR do fall into this category: they raise profits and advance society’s well-being at the same time. Examples include establishing a reputation for dealing honestly with employees, suppliers and customers. This is the win-win kind of CSR—the sort that fails to impress much of civil society. Perhaps it would be better to call it simply “good management”.

Turning back to those two questions, however, note that there are three other possible answers as well. These are mapped out in the table. Some kinds of CSR reduce profits but raise social welfare (this is what civil society likes best: call it “borrowed virtue”, for reasons to be explained in a moment). There is also CSR that raises profits but reduces social welfare (“pernicious CSR”), and CSR that reduces both profits and welfare (a polite name for which might be “delusional CSR”). Consider some examples.

To begin with, win-win, or “good management”. There is a lot of it about. Many executives in the CSR movement deserve credit for testing and drawing attention to novel practices that can yield these good results. Their ideas may not be applicable in all or even most companies, but their success in particular cases is impressive.

One of the most enthusiastic and persuasive evangelists of win-win CSR is Marc Benioff, head of salesforce.com, a strikingly successful internet-based business-services company. In his book, “Compassionate Capitalism”, he explains, among other things, how good corporate citizenship can be used to attract, retain and motivate the best workers. His company encourages its staff to devote time, at the firm’s expense, to charitable works. In complementary ways, it also provides flexibility in working hours and conditions. The character of the firm, as perceived by its employees and its customers alike, is closely associated with this commitment to good causes.

All this seems to pay. Mr Benioff argues that this draws the right kind of people to the firm—team players, joiners, volunteers, generous and committed colleagues with a sense of loyalty to the enterprise. This kind of corporate philanthropy, which marries good works with a clever way of sorting and motivating staff, is undoubtedly catching on.

When you press a CEO for details of a company’s CSR policies, and for their business rationale, you find that every firm believes that its CSR actions fall in the win-win box. No chief executive wants to believe that the firm’s various services to the community might reduce social welfare, and none seems willing to admit that his enlightened management practices might reduce profits—what would the shareholders make of that? But those other cells of the matrix are far from empty.

A clear instance of an action that reduces profits while (presumably) improving social welfare is a straightforward cash donation to charity. The donations featured in the Giving List fall into this category. Sums donated in this way have soared recently in response to the Asian tsunami. You might suppose that devoting profit to the public interest is CSR at its best, or at any rate its noblest. The enlightened company is surrendering some of its earnings to make the world a better place. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits-

The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits by

The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970. Copyright @ 1970 by The New York Times Company.

When I hear businessmen speak eloquently about the “social responsibilities of business in a free-enterprise system,” I am reminded of the wonderful line about the Frenchman who discovered at the age of 70 that he had been speaking prose all his life. The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned “merely” with profit but also with promoting desirable “social” ends; that business has a “social conscience” and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers. In fact they are–or would be if they or anyone else took them seriously–preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.

The discussions of the “social responsibilities of business” are notable for their analytical looseness and lack of rigor. What does it mean to say that “business” has responsibilities? Only people can have responsibilities. A corporation is an artificial person and in this sense may have artificial responsibilities, but “business” as a whole cannot be said to have responsibilities, even in this vague sense. The first step toward clarity in examining the doctrine of the social responsibility of business is to ask precisely what it implies for whom.

Presumably, the individuals who are to be responsible are businessmen, which means individual proprietors or corporate executives. Most of the discussion of social responsibility is directed at corporations, so in what follows I shall mostly neglect the individual proprietors and speak of corporate executives.

In a free-enterprise, private-property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom. Of course, in some cases his employers may have a different objective. A group of persons might establish a corporation for an eleemosynary purpose–for example, a hospital or a school. The manager of such a corporation will not have money profit as his objective but the rendering of certain services.

In either case, the key point is that, in his capacity as a corporate executive, the manager is the agent of the individuals who own the corporation or establish the eleemosynary institution, and his primary responsibility is to them.

Needless to say, this does not mean that it is easy to judge how well he is performing his task. But at least the criterion of performance is straightforward, and the persons among whom a voluntary contractual arrangement exists are clearly defined.

Of course, the corporate executive is also a person in his own right. As a person, he may have many other responsibilities that he recognizes or assumes voluntarily–to his family, his conscience, his feelings of charity, his church, his clubs, his city, his country. He ma}. feel impelled by these responsibilities to devote part of his income to causes he regards as worthy, to refuse to work for particular corporations, even to leave his job, for example, to join his country’s armed forces. Ifwe wish, we may refer to some of these responsibilities as “social responsibilities.” But in these respects he is acting as a principal, not an agent; he is spending his own money or time or energy, not the money of his employers or the time or energy he has contracted to devote to their purposes. If these are “social responsibilities,” they are the social responsibilities of individuals, not of business.

What does it mean to say that the corporate executive has a “social responsibility” in his capacity as businessman? If this statement is not pure rhetoric, it must mean that he is to act in some way that is not in the interest of his employers. For example, that he is to refrain from increasing the price of the product in order to contribute to the social objective of preventing inflation, even though a price in crease would be in the best interests of the corporation. Or that he is to make expenditures on reducing pollution beyond the amount that is in the best interests of the corporation or that is required by law in order to contribute to the social objective of improving the environment. Or that, at the expense of corporate profits, he is to hire “hardcore” unemployed instead of better qualified available workmen to contribute to the social objective of reducing poverty.

In each of these cases, the corporate executive would be spending someone else’s money for a general social interest. Insofar as his actions in accord with his “social responsibility” reduce returns to stockholders, he is spending their money. Insofar as his actions raise the price to customers, he is spending the customers’ money. Insofar as his actions lower the wages of some employees, he is spending their money.

The stockholders or the customers or the employees could separately spend their own money on the particular action if they wished to do so. The executive is exercising a distinct “social responsibility,” rather than serving as an agent of the stockholders or the customers or the employees, only if he spends the money in a different way than they would have spent it.

But if he does this, he is in effect imposing taxes, on the one hand, and deciding how the tax proceeds shall be spent, on the other.

This process raises political questions on two levels: principle and consequences. On the level of political principle, the imposition of taxes and the expenditure of tax proceeds are governmental functions. We have established elaborate constitutional, parliamentary and judicial provisions to control these functions, to assure that taxes are imposed so far as possible in accordance with the preferences and desires of the public–after all, “taxation without representation” was one of the battle cries of the American Revolution. We have a system of checks and balances to separate the legislative function of imposing taxes and enacting expenditures from the executive function of collecting taxes and administering expenditure programs and from the judicial function of mediating disputes and interpreting the law.

Here the businessman–self-selected or appointed directly or indirectly by stockholders–is to be simultaneously legislator, executive and, jurist. He is to decide whom to tax by how much and for what purpose, and he is to spend the proceeds–all this guided only by general exhortations from on high to restrain inflation, improve the environment, fight poverty and so on and on.

The whole justification for permitting the corporate executive to be selected by the stockholders is that the executive is an agent serving the interests of his principal. This justification disappears when the corporate executive imposes taxes and spends the proceeds for “social” purposes. He becomes in effect a public employee, a civil servant, even though he remains in name an employee of a private enterprise. On grounds of political principle, it is intolerable that such civil servants–insofar as their actions in the name of social responsibility are real and not just window-dressing–should be selected as they are now. If they are to be civil servants, then they must be elected through a political process. If they are to impose taxes and make expenditures to foster “social” objectives, then political machinery must be set up to make the assessment of taxes and to determine through a political process the objectives to be served.

This is the basic reason why the doctrine of “social responsibility” involves the acceptance of the socialist view that political mechanisms, not market mechanisms, are the appropriate way to determine the allocation of scarce resources to alternative uses.

On the grounds of consequences, can the corporate executive in fact discharge his alleged “social responsibilities?” On the other hand, suppose he could get away with spending the stockholders’ or customers’ or employees’ money. How is he to know how to spend it? He is told that he must contribute to fighting inflation. How is he to know what action of his will contribute to that end? He is presumably an expert in running his company–in producing a product or selling it or financing it. But nothing about his selection makes him an expert on inflation. Will his hold ing down the price of his product reduce inflationary pressure? Or, by leaving more spending power in the hands of his customers, simply divert it elsewhere? Or, by forcing him to produce less because of the lower price, will it simply contribute to shortages? Even if he could answer these questions, how much cost is he justified in imposing on his stockholders, customers and employees for this social purpose? What is his appropriate share and what is the appropriate share of others?

And, whether he wants to or not, can he get away with spending his stockholders’, customers’ or employees’ money? Will not the stockholders fire him? (Either the present ones or those who take over when his actions in the name of social responsibility have reduced the corporation’s profits and the price of its stock.) His customers and his employees can desert him for other producers and employers less scrupulous in exercising their social responsibilities.

This facet of “social responsibility” doc trine is brought into sharp relief when the doctrine is used to justify wage restraint by trade unions. The conflict of interest is naked and clear when union officials are asked to subordinate the interest of their members to some more general purpose. If the union officials try to enforce wage restraint, the consequence is likely to be wildcat strikes, rank-and-file revolts and the emergence of strong competitors for their jobs. We thus have the ironic phenomenon that union leaders–at least in the U.S.–have objected to Government interference with the market far more consistently and courageously than have business leaders.

The difficulty of exercising “social responsibility” illustrates, of course, the great virtue of private competitive enterprise–it forces people to be responsible for their own actions and makes it difficult for them to “exploit” other people for either selfish or unselfish purposes. They can do good–but only at their own expense.

Many a reader who has followed the argument this far may be tempted to remonstrate that it is all well and good to speak of Government’s having the responsibility to impose taxes and determine expenditures for such “social” purposes as controlling pollution or training the hard-core unemployed, but that the problems are too urgent to wait on the slow course of political processes, that the exercise of social responsibility by businessmen is a quicker and surer way to solve pressing current problems.

Aside from the question of fact–I share Adam Smith’s skepticism about the benefits that can be expected from “those who affected to trade for the public good”–this argument must be rejected on grounds of principle. What it amounts to is an assertion that those who favor the taxes and expenditures in question have failed to persuade a majority of their fellow citizens to be of like mind and that they are seeking to attain by undemocratic procedures what they cannot attain by democratic procedures. In a free society, it is hard for “evil” people to do “evil,” especially since one man’s good is another’s evil.

I have, for simplicity, concentrated on the special case of the corporate executive, except only for the brief digression on trade unions. But precisely the same argument applies to the newer phenomenon of calling upon stockholders to require corporations to exercise social responsibility (the recent G.M crusade for example). In most of these cases, what is in effect involved is some stockholders trying to get other stockholders (or customers or employees) to contribute against their will to “social” causes favored by the activists. Insofar as they succeed, they are again imposing taxes and spending the proceeds.

The situation of the individual proprietor is somewhat different. If he acts to reduce the returns of his enterprise in order to exercise his “social responsibility,” he is spending his own money, not someone else’s. If he wishes to spend his money on such purposes, that is his right, and I cannot see that there is any objection to his doing so. In the process, he, too, may impose costs on employees and customers. However, because he is far less likely than a large corporation or union to have monopolistic power, any such side effects will tend to be minor.

Of course, in practice the doctrine of social responsibility is frequently a cloak for actions that are justified on other grounds rather than a reason for those actions.

To illustrate, it may well be in the long run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That may make it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses from pilferage and sabotage or have other worthwhile effects. Or it may be that, given the laws about the deductibility of corporate charitable contributions, the stockholders can contribute more to charities they favor by having the corporation make the gift than by doing it themselves, since they can in that way contribute an amount that would otherwise have been paid as corporate taxes.

In each of these–and many similar–cases, there is a strong temptation to rationalize these actions as an exercise of “social responsibility.” In the present climate of opinion, with its wide spread aversion to “capitalism,” “profits,” the “soulless corporation” and so on, this is one way for a corporation to generate goodwill as a by-product of expenditures that are entirely justified in its own self-interest.

It would be inconsistent of me to call on corporate executives to refrain from this hypocritical window-dressing because it harms the foundations of a free society. That would be to call on them to exercise a “social responsibility”! If our institutions, and the attitudes of the public make it in their self-interest to cloak their actions in this way, I cannot summon much indignation to denounce them. At the same time, I can express admiration for those individual proprietors or owners of closely held corporations or stockholders of more broadly held corporations who disdain such tactics as approaching fraud.

Whether blameworthy or not, the use of the cloak of social responsibility, and the nonsense spoken in its name by influential and prestigious businessmen, does clearly harm the foundations of a free society. I have been impressed time and again by the schizophrenic character of many businessmen. They are capable of being extremely farsighted and clearheaded in matters that are internal to their businesses. They are incredibly shortsighted and muddleheaded in matters that are outside their businesses but affect the possible survival of business in general. This shortsightedness is strikingly exemplified in the calls from many businessmen for wage and price guidelines or controls or income policies. There is nothing that could do more in a brief period to destroy a market system and replace it by a centrally controlled system than effective governmental control of prices and wages.

The shortsightedness is also exemplified in speeches by businessmen on social responsibility. This may gain them kudos in the short run. But it helps to strengthen the already too prevalent view that the pursuit of profits is wicked and immoral and must be curbed and controlled by external forces. Once this view is adopted, the external forces that curb the market will not be the social consciences, however highly developed, of the pontificating executives; it will be the iron fist of Government bureaucrats. Here, as with price and wage controls, businessmen seem to me to reveal a suicidal impulse.

The political principle that underlies the market mechanism is unanimity. In an ideal free market resting on private property, no individual can coerce any other, all cooperation is voluntary, all parties to such cooperation benefit or they need not participate. There are no values, no “social” responsibilities in any sense other than the shared values and responsibilities of individuals. Society is a collection of individuals and of the various groups they voluntarily form.

The political principle that underlies the political mechanism is conformity. The individual must serve a more general social interest–whether that be determined by a church or a dictator or a majority. The individual may have a vote and say in what is to be done, but if he is overruled, he must conform. It is appropriate for some to require others to contribute to a general social purpose whether they wish to or not.

Unfortunately, unanimity is not always feasible. There are some respects in which conformity appears unavoidable, so I do not see how one can avoid the use of the political mechanism altogether.

But the doctrine of “social responsibility” taken seriously would extend the scope of the political mechanism to every human activity. It does not differ in philosophy from the most explicitly collectivist doctrine. It differs only by professing to believe that collectivist ends can be attained without collectivist means. That is why, in my book Capitalism and Freedom, I have called it a “fundamentally subversive doctrine” in a free society, and have said that in such a society, “there is one and only one social responsibility of business–to use it resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

Why do Corporations need to be socially responsible to build their “reputation capital”?

For all the burgeoning popularity of corporate social responsibility – the art of “ doing well by doing good” – its benefits remain unproven. It is all well and good to say that a globalzing company needs to take account of social problems in its new markets, or that social responsibility will be its own reward, in happier employees, lower legal costs and improved productivity. But at heart, for many companies, corporate social responsibility is still just a matter of branding, and a murky one at that. Look at McDonald’s and the Body Shop, for example. The former is still a target of consumer derision and lawsuits despite its introduction of healthier food. The environmentally friendly reputation of the Body Shop, on the other hand, has long outpaced its actual investment in eco-friendly processes.

“Building Reputational Capital,” by Kevin Jackson, a professor of legal and ethical studies at Fordham University in New York, argues that corporations need to be socially responsible to build their “reputational capital,” which is similar to, but bigger than, any brands they might market. A company with lots of such capital will be able to attract.

What does corporate social responsibility really mean?

IT WILL no longer do for a company to go quietly about its business, telling no lies and breaking no laws, selling things that people want, and making money. That is so passe. Today, all companies, but especially big ones, are enjoined from every side to worry less about profits and be socially responsible instead. Surprisingly, perhaps, these demands have elicited a willing, not to say avid, responsible boardrooms everywhere.

Companies at every opportunity now pay elaborate obeisance to the principles of corporate social responsibility. They have CSR officers, CSR consultants, CSR departments, and CSR initiatives coming out of their ears. A good thing, too, you might think. About time. What kind of idiot or curmudgeon would challenge the case for businesses to behave more responsible? Thank you for asking.

The benefits of corporate social responsibility-

Westpac believes that responding to environmental and social management opportunities is totally consistent with its objective of enhancing shareholder value.

In a competitive employment market, people want to work for a company with a strong reputation, based on a decent set of values and behaviors. A clear public commitment to and differentiation around corporate responsibility is a source of competitive advantage. An indication of this for Westphalia is the increase in graduate applications from 2,677 in 2002 to 7,159 in 2003.

For current employees, corporate responsibility both directly influences employee performance via employee commitment and helps secure organizational attention to managerial issues, such as employee turnover and occupational health and safety, which in turn drive business performance.

Corporate responsibility drives improved environmental and social outcomes that concurrently result in operational efficiency and cost containment. External reporting and public commitment to OHS performance has helped drive a reduction in workplace injuries. The safer environment is a more efficient environment that pre-empts the cost and reputational impacts of remedial programs, legal action and media exposure. In addition, data on resource use is collected and externally reported via Westpac’s participation in the Australian Government Greenhouse Challenge initiative. Participation has contributed to imorve resource usage.

In recent years, Wespac’s reputation with important stakeholder groups has been considerably strengthened through engagement. Perceptions have been formed from direct experience through both structured and ad hoc dialogue and also via word of mouth communication and the contribution o intermediaries, including the media.

Westpac has also received many CSR awards, including being ranked number one in the global banking sector by the Dow Jones Sustainability Index for the second year in a row, and one of 22 companies to score 10.0 (the highest rating) amongst 1,100 global organizations, and only Australian company to do so, in the Government Metrics International Global Governance Ratings 2004.

Methodology

Percentage spending in the corporate social responsibilities and dividend earning ratio of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited. Here, we find out the relationship by statistical test. We try to relate between those variables by calculating correlation analysis. Here we have to create some data tables.

History of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited

The Dutch-Bangla Bank Ltd. (DBBL) is the first Euro-Bangla Joint Venture Scheduled Commercial Bank in the private sector in Bangladesh. The Bank commenced operation from 3rd June, 1996 with equity participation from FMO, The Netherlands. Since inception besides progressive banking activities, Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited has been taking part in different national activities promoting sports, culture, social awareness, etc. With this end in view, Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited rendered contribution to Mini World Cup Cricket Tournament-1999, National Youth Fair-1999, National Olympic Day Run, 3 Day Cricket Match between Bangladesh and West Indies, etc.

DBBL’s profile was enhanced beyond the industry arena due to its promoting and patronizing sporting and social events in Bangladesh. Bangladesh is the youngest member of Test playing family of Cricket. Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited has become a part of Test Cricket history by sponsoring the historic inaugural Test match between Bangladesh and India. This historic event took place from November 10 to November 14, 2000 and it was graced with the name “Dutch-Bangla Bank Inaugural Test Match”. DBBL also took part in “Dhaka International Trade Fair-2000 (DITF- 2000)” taking booth as well as sponsoring the Main Gate, which received tremendous acclamation from the people visited the fair. The main function in the booth was to receive deposits from the clients, opening accounts, issuing pay-orders and to attend the visitor’s queries about DBBL and its various products. During 39 days of operation, the booth received a total of Taka 125.00 million from the clients.

The ethos & essence that manifest the driving force for the Bank’s progress as an institution par excellence to customer satisfaction, state of the art products & services, and competence and efficiency based on professionalism indeed. The Bank has remained dynamic in its continued efforts to improve & increase core competence & service efficiency by constantly upgrading product quality, service standards, protocol and their effective participation making use of state of the art technology.

Global Banking has changed rapidly and DBBL has worked hard to adapt to these changes. The bank looks forward with excitement and a commitment to bring greater benefits to customers.

DBBL dedicated their service to the Nation through active financial participation in all segments of the economy, Industry, Trade & Commerce, Agriculture, Service Sector etc. DBBL is keeping pace with the changing environment.

With all harness together out strengths and putting our heads together in unity of purpose, DBBL will reach Herculean heights in the domain that is its forte- Banking & financial Services.

Dutch Bangla Bank Limited (DBBL) a public company limited by shares, incorporated in Bangladesh in the year 1995 under companies Act 1994.

DBBL- a Bangladesh European private joint venture scheduled commercial bank commenced formal operation from June 3, 1996. The head office of the Bank is located at Senakalyan Bhaban (4th floor),195, Motijheel C/A, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

With 30%. equity holding, the Netherlands Development Finance company (FMO) of the Netherlands is the international co-sponsor of the Bank. Out of the rest 70%, 60% equity has been provided by prominent local entrepreneurs and industrialists & the rest 10% shares is the public issue. During the initial operating year (1996-1997) the bank received skill augmentation technical assistance from ABN Amro Bank of the Netherlands.

Starting with one Branch in 1996, DBBL has expanded to fifteen branches including six Branches outside of the capital. We have a plan to open five(5)more Branches during the year 2002. To provide client services all over Bangladesh it has established a wide correspondent banking relationship with a number of local banks. To facilitate international trade transactions, it has arranged correspondent relationship with large number of international banks which are active across the globe.

Sample Design

In our study we have selected a particular organization. Sample has selected different form of business based on the performance in the share price.

Data Collection

Information of the share price has collected from Head office of the Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited. Profit data, corporate social responsibility, share price, earning per share, dividend per share, expending in the corporate social responsibility has collected from annual report 2004 of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited. Information regarding environmental concern materials has collected from other literature review.

Corporate Social Responsibility of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited

Now a days businessmen speak about the corporate social responsibility significantly. Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited believe that only profit earning is not the final goal of a business enterprise. The reality is that business without society and society without business will not bring any true benefit. So it is important for a business to achieve its goal adjusting with society. Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited is involved in various types of social activities from its beginning. Now social activities of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited has increased immensely. In this respect board of directors of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited has increased its funds for social responsibilities form 2.5% to 5 percent of its total profit. The Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited is involved forming the following social activities:

1. Under Dhaka City beautification project Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited performs the following activities-

a) Water foara- Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited has set up water foara at Minto road in Dahka.

b) As a part of Dhaka City beautification project Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited constructs fence around the tree and color them.

c) Under Dhaka City beautification project Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited performs tree plantation program in the island of the road.

2. Under social activities program the tasks that performed by Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited during 2004 are given below-

a) To help flood affected people Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides a cheek of Tk. 5000000 to the prime minister relief fund.

b) To help cold sheparing people Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides 2000 worm clothes to the prime minister’s relief fund.

c) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides five hundred scholarship for the poor and meritorious students.

d) During flood in 2004, Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides relief for the flood-affected people directly.

e) During 2004, Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides a cheek of Tk. 3000000 as Zakat to the religion state minister.

f) During 2004, Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides Tk.1500000 for the modernization of economics department of Dhaka University.

g) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited earning patient living with aids project to help HIV patient.

h) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides Tk. 3488000 to hockey foundation of Bangladesh for foreign coach and physical training of the players.

i) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides Tk. 4000000 for the foundation of Ahashania Mission Cancer Hospital.

j) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides Tk. 200000 to help the blind.

k) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited helps Sir Solimullah Medical College Hospital for establishing breast feeding management center during 2004.

l) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides 750 bundle GCI sheet for tornado damaged people of Mymensingh and Netrakona.

m) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides fund to cure childhood cancer.

n) Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provides financial support to the following NGO’s-

- Special Education for the Intellectually Disabled Children (SEID)

- Endanger Health Bangladesh.

- Nurture Center for Disabled and Paralyzed (NCDP).

- Society for the Education of the Intellectually Disabled, Bangladesh.

Limitations

There are few organization in Bangladesh which are actively involved in social activities. The most prominent of them is Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited. So we have worked on the Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited. We could not include more firms because of time limitation and rules and regulations of the firm. Since Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited starts its operations few years ago in Bangladesh, we have not got enough data for our study. So we have showed relationship by co-relating between profit earning ratio and net profit, profit earning ratio and dividend per share and profit earning ratio and expenditure of corporate social responsibility. Our study based on secondary data. Although we have some limitation, we have tried to show the relationship how social an activity of a firm affects its profit.

Data Analysis

From the collected data we have find out the trend of dividend ratio and also trend the profit. Then we have to find the correlation between the available data regarding environmental and these 4 trends. A positive correlation will prove that environmental reporting has positively influenced on share prices and vise-versa.

We have find out the relationship among 4 variables, In the first case the relationship between profit earning ratio and net profit from 2001 – 2004.

In the second case the relationship profit earning ratio and dividend per share from 2001 – 2004 and in the 3rd Case the relationship between profit earning ratio and expanding for corporate social responsibility by Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited.

Statistical Test (Correlation analysis)

Profit earning ratio table from 2001 – 2004

Serial No. | Year | Profit earning ratio |

1 | 2001 | 5.30 |

2 | 2002 | 4.64 |

3 | 2003 | 4.15 |

4 | 2004 | 15.84 |

Net profit table from 2001 – 2004

Serial No. | Year | Profit earning ratio |

1 | 2001 | 162.80 |

2 | 2002 | 177.60 |

3 | 2003 | 210.16 |

4 | 2004 | 236.35 |

Dividend per share from 2001 – 2004

Serial No. | Year | Profit earning ratio |

1 | 2001 | 17.5 |

2 | 2002 | 20.00 |

3 | 2003 | 20.00 |

4 | 2004 | 22.50 |

Expenditure to corporate social responsibility from 2001 – 2004

Serial No. | Year | Profit earning ratio |

1 | 2001 | 2.50 |

2 | 2002 | 2.50 |

3 | 2003 | 2.50 |

4 | 2004 | 5.00 |

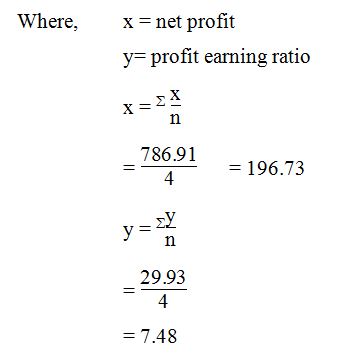

Calculated Value:

Calculate the relationship between profit earning ratio and net profit from 2001 – 2004

Sl. No. | Year | (x) | (x-x) | (x-x)2 | y | (y-y) | (y-y)2 | (x-x) ´ (y-y) |

1 | 2001 | 162.80 | -33.93 | 1151.24 | 5.30 | -2.18 | 4.75 | 73.96 |

2 | 2002 | 177.60 | -19.13 | 365.95 | 4.64 | -2.84 | 8.06 | 54.33 |

3 | 2003 | 210.16 | 13.43 | 180.36 | 4.15 | -3.33 | 11.09 | -44.72 |

4 | 2004 | 236.35 | 39.62 | 1569.74 | 15.84 | 8.36 | 69.89 | 331.22 |

| åx=786.91 | å(x-x)2 =3267.29 | åy=29.93 | å(y-y)2 =93.79 | å(x-x) (y-y)=414.79 |

Findings:

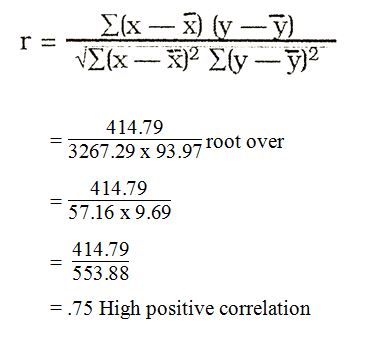

We have found the relationship among 4 valuables. After calculating correlation by statistical test we see, that the high positive relationship between profit earning ratio and net profit that is .75. In the second case the highly positive relationship between profit earning ratio and dividend per share, that is .77. And in the 3rd case more highly positive relationship between the profit earning ratio and expenditure of corporate social responsibility of Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited. For this test we have taken the three tables and 4 years data. Which does the Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited provide. So we can say that, the corporate social responsibilities positively affect by the organizations profit earning ratio and also effect the share price of that organization.

Conclusion

If we want to get a suitable decision, we need at least 10 years data about related test. Because of shortage of data we cannot go for chi-square test Although we have not find out the relationship by using chi-square test, we showed the relationship by correlating profit earning ratio and net profit, profit earning ratio and dividend per share, profit earning and expenditure of corporate social responsibility.

Finally, we can say that, the environmental reporting of a business enterprise positively affects its profit earning ratio and share price.