Localized breast cancer is handled differently than metastatic breast cancer. As a result, during the diagnostic/staging procedure, oncologists often look for evidence of metastasis. Breast cancer can also spread after a patient has been diagnosed. Patients are usually scheduled for numerous imaging scans during and after therapy to look for evidence of metastases.

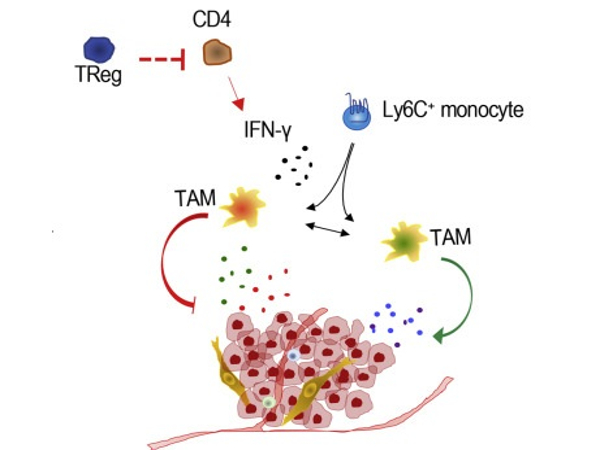

Macrophages, a type of immune cell, are used by metastatic breast cancer cells to support the spread of cancer metastases in the lungs. The reprogrammed macrophages cause blood vessel cells to secrete a cocktail of metastasis-promoting proteins, which are found in the so-called metastatic niche. This was demonstrated in mice transplanted with human breast cancer cells by scientists from the German Cancer Research Center and the Stem Cell Institute HI-STEM*. The work enabled the scientists to identify new targets and develop initial concepts to better restrain the metastatic spread of breast cancer.

Breast cancer develops as aberrant cells infect healthy tissues around it. In most cases, breast cancer spreads to other regions of the afflicted breast before spreading to surrounding lymph nodes. If malignant cells make their way into the lymphatic system, they can spread to other regions of the body. Cancer spreads within the body as individual cells detach from the original tumor and move to other bodily regions via the bloodstream or lymphatic system. They must communicate with their new surroundings via a multitude of molecular interactions before they may grow into a metastasis at a secondary site.

In order to settle in this new, hostile milieu, the cancer cells corrupt the microenvironment to support their growth. Researchers refer to this as the tumor cells creating a “metastatic niche.”

Thordur Oskarsson

“In order to settle in this new, hostile milieu, the cancer cells corrupt the microenvironment to support their growth,” says Thordur Oskarsson of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the stem cell institute HI-STEM. Researchers refer to this as the tumor cells creating a “metastatic niche.”

In metastasis, blood vessels play a unique role. Tumor cells that have become detached prefer to remain in their nearby surroundings. Many studies have already established that interactions between cancer cells and endothelial cells lining the inside of arteries are critical for metastasis. The specifics of this molecular exchange, on the other hand, remain mostly unclear.

A team led by Oskarsson has now investigated these interactions during metastatic colonization of the lung by breast cancer cells in mice. The researchers first observed that four genes in the lung endothelial cells showed a particularly strong increase in activity three weeks after the onset of metastasis. They encode four proteins that are secreted into the microenvironment (Inhbb, Lama1, Scgb3a1, and Opg**), which both individually and in combination promote the development of lung metastases.

Inhbb and Scgb3a1 confer stem cell properties to cancer cells, Opg prevents programmed cell death — apoptosis — and Lama1 supports adhesion-mediated cell survival. Importantly, high expression of these four newly identified niche factors correlates with both shortened relapse-free survival and shortened overall survival of breast cancer patients.

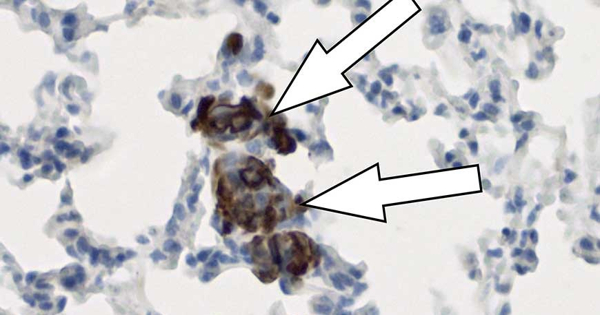

But how can cancer cells access the pulmonary endothelium to release the metastasis-promoting protein cocktail? To the amazement of the investigators, cancer cells do not perform this function directly, but rather rely on a type of innate immune system cell called macrophages.

“These macrophages, which frequently live near lung blood arteries, are activated by tenascin, an extracellular matrix protein generated by breast cancer cells,” explains Tsunaki Hongu, the study’s first author. Tenascin is implicated in the progression of various malignancies. After being activated by tenascin, macrophages generate a variety of molecules that stimulate the creation of the cancer-promoting protein cocktail in endothelial cells. By eliminating macrophages or their activity, using specific molecular agents, the investigators could show that these cells are crucial for the production of the metastasis-promoting protein cocktail.

Oskarsson, who currently works at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida, sums it up as follows: “The interplay between cancer cells, macrophages, and endothelial cells is astounding in its complexity. We were able to find a range of beginning places for new therapies against breast cancer metastasis by better understanding the various proteins and other components involved in these metastatic relationships. We have already established preliminary therapy thoughts for this, which we must now validate in additional research.”