According to studies conducted by the Future Sustainable Food Systems research group at the University of Helsinki in collaboration with the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, fungus-produced ovalbumin has the potential to reduce the environmental impact of chicken egg white powder.

This is especially true when low-carbon energy sources are used in the manufacturing process. Because of the high-quality protein it contains, chicken egg white powder is a widely utilized component in the culinary sector.

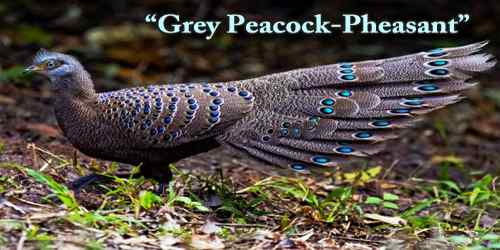

In 2020, the annual consumption of egg proteins was estimated to be over 1.6 million tons, with the market projected to grow in the coming years. The rising demand raises concerns about both sustainability and ethical behavior.

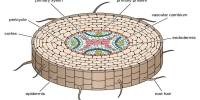

Parts of the egg white powder production chain, such as the breeding of birds for egg production, contribute to water scarcity, biodiversity loss, and deforestation.

Furthermore, industrial chicken raising has resulted in zoonotic disease epidemics by acting as a reservoir for human viruses. The food sector is increasingly interested in finding sustainable alternatives to animal-based proteins.

When utilized for recombinant ingredient synthesis, cellular agriculture, also known as precision fermentation, is a biotechnology-based method that uses a microbial production system to decouple the production of animal proteins from animal farming.

According to our research, this means that the fungus-produced ovalbumin reduced land use requirements by almost 90 percent and greenhouse gases by 31-55 percent compared to the production of its chicken-based counterpart. In the future, when production is based on low carbon energy, precision fermentation has the potential to reduce the impact even by up to 72 percent.

Natasha Järviö

“For example, more than half of the egg white powder protein content is ovalbumin. VTT has succeeded in producing ovalbumin with the help of the filamentous ascomycete fungus Trichoderma reesei. The gene carrying the blueprints for ovalbumin is inserted by modern biotechnological tools into the fungus which then produces and secretes the same protein that chickens produce. The ovalbumin protein is then separated from the cells, concentrated, and dried to create a final functional product,” says Dr. Emilia Nordlund from VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland.

Because cell-cultured products require more electricity than traditional agricultural products, the type of energy source employed has an impact on the level of environmental impact. The amount of agricultural inputs required for bacteria to produce ovalbumin, such as glucose, is often much smaller per kilogram of protein powder.

“According to our research, this means that the fungus-produced ovalbumin reduced land use requirements by almost 90 percent and greenhouse gases by 31-55 percent compared to the production of its chicken-based counterpart. In the future, when production is based on low carbon energy, precision fermentation has the potential to reduce the impact even by up to 72 percent,” says Doctoral Researcher Natasha Järviö from the University of Helsinki.

The results for the environmental impact of water use were less compelling, indicating a significant degree of reliance on the assumed location of the ovalbumin production facility.

In general, the study demonstrates that precision fermentation technology has the potential to improve protein production sustainability, which can be further enhanced by the use of low-carbon energy sources.