The length of a woman’s menstrual cycle frequently lengthens as she approaches menopause. According to a recent study headed by University of Pittsburgh researchers, the timing of these alterations might give hints about a person’s risk of developing heart disease.

The length of a woman’s menstrual cycle varies, but on average, she has a period every 28 days. It’s typical to have cycles that are longer or shorter than this, ranging from 21 to 40 days. A woman will have roughly 480 periods between the ages of 12 and 52, or less if she has had any pregnancies.

The study, which was published today (October 13, 2021) in Menopause, characterizes cycle length changes during the menopause transition and finds that women whose cycle length increased two years before their final menstrual period had better vascular health than those whose cycle length remained stable during this transition.

Changes in cycle length, when combined with other menopause-related features and health measurements, may help physicians identify which individuals are at higher or lower risk of cardiovascular disease and propose preventative treatments. Women’s cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the main cause of mortality, with a significant increase in risk after menopause with coronary heart disease developing several years later than males.

Cardiovascular disease is the No. 1 killer of women, and the risk significantly increases after midlife, which is why we think that menopause could contribute to this disease.

Samar El Khoudary

“Cardiovascular disease is the No. 1 killer of women, and the risk significantly increases after midlife, which is why we think that menopause could contribute to this disease,” said lead author Samar El Khoudary, Ph.D., associate professor of epidemiology at Pitt’s Graduate School of Public Health.

“Menopause isn’t a simple matter of pressing a button. It’s a multi-stage transition during which women go through a variety of changes that may put them at risk for cardiovascular disease. Changes in cycle length, which are connected to hormone levels, are a simple indicator that can help us determine who is more vulnerable.”

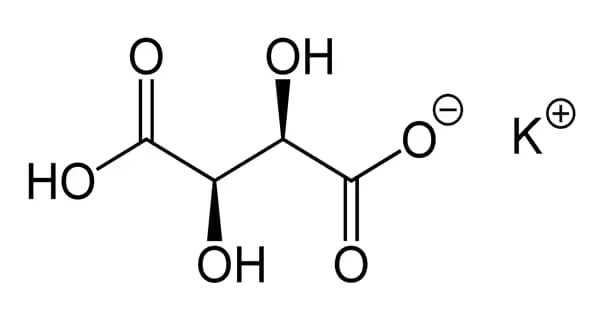

A menstrual cycle lasts roughly 28 days on average, however, this varies greatly across people. Long and irregular cycles during reproductive years have been linked to cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, osteoporosis, and other conditions, and those with frequent short cycles spend more time with high estrogen levels than those with fewer long cycles.

Hormones are in charge of the menstrual cycle. Oestrogen levels rise throughout each cycle, causing the ovary to grow and produce an egg (ovulation). During the menstrual cycle, vaginal secretions (also known as vaginal discharge) alter.

El Khoudary and her colleagues questioned if variations in menopausal cycle duration may also predict future cardiovascular health. The researchers used data from 428 individuals in the continuing Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation to address this issue.

The women in the research were 45 to 52 years old at the time of recruitment and were followed for up to ten years or until they were postmenopausal. The researchers gathered menstrual cycle data during the menopausal transition and used arterial stiffness or artery thickness to determine cardiovascular risk after menopause.

Women acquire coronary heart disease (CHD) many years later than males, with a significant rise in CHD risk throughout midlife, which occurs around the time of menopause. This finding led to the notion that the MT has a role in the increased risk.

During the menopausal transition, the researchers discovered three unique paths in menstrual cycle duration. Roughly 62 percent of individuals had stable periods that didn’t alter much before menopause, whereas about 16 percent and 22 percent had an early or late rise, defined as a five-year or two-year increase in cycle duration before menopause, respectively.

The available information on the impact of lifestyle measures, as well as the use of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) and lipid-lowering treatment alternatives, on CVD risk, is also examined, with a special focus on the timing of these interventions as they relate to menopause transition (MT).

Women in the late rise group had considerably better assessments of arterial hardness and thickness than women with stable cycles, indicating a lower risk of cardiovascular disease. The arterial health of women in the early increase group was the worst.

“These findings are important because they show that we cannot treat women as one group: Women have different menstrual cycle trajectories over the menopause transition, and this trajectory seems to be a marker of vascular health,” said El Khoudary.

“This information adds to the toolkit that we are developing for clinicians who care for women in midlife to assess cardiovascular disease risk and brings us closer to personalizing prevention strategies.”

The researchers believe that during menopause, menstrual cycle trajectories reflect hormone levels, which in turn affect cardiovascular health. They want to study hormone changes in the future to test this theory.

According to El Khoudary, it’s unclear why people with stable cycles had a higher risk of cardiovascular disease than those with late increases. Although studies show that elevated estrogen protects the heart in young women with short periods, this hormone may be less beneficial as people become older.

El Khoudary also wants to see if menstrual cycle patterns are connected to other cardiovascular risk factors including abdominal obesity, which she discovered to be linked to heart disease risk in menopausal women earlier.