A new packaging tray developed by McMaster University researchers can alert consumers whether packages of raw or cooked chicken, for example, contain Salmonella or other potentially harmful bacteria.

The new technology will make it possible for producers, retailers, and consumers to determine in real-time whether the contents of a sealed food package are contaminated without having to open it. This will prevent consumers from being exposed to contamination while also streamlining labor-intensive and expensive lab-based detection processes, which currently add a lot of time and money to the food production process.

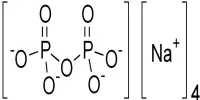

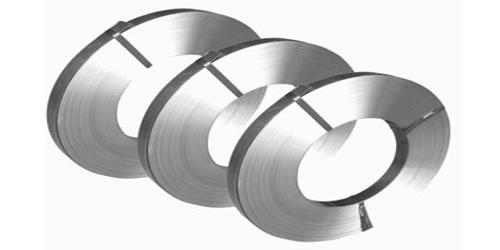

A food-safe reagent is used to line the shallow boat-shaped prototype tray, enabling an integrated sensor to detect and alert users to the presence of Salmonella. The technology can readily be adapted to test for other common food-borne contaminants, such as E. coli and Listeria.

“This is something that can benefit everyone,” says researcher Akansha Prasad, the co-lead author of a paper that describes the invention, published June 26 in the journal Advanced Materials. “We’re hoping this technology will save lives, money, and food waste.”

“There is so much at stake with food safety,” says researcher Shadman Khan, co-lead author on the paper. “We wanted to develop a system that was reliable, quick, affordable, and easy to use.”

Being able to combine packaging and Salmonella detection in one system is already very promising. It also shows that we can add sensing probes for other food-borne pathogens to the same system so the package will check for all of them at once. That’s the next step for us, and we’re already working on it.

Professor Yingfu Li

Juices are directed to a sensor that is implanted in a window at the bottom of the tray by its sloping sides. Users can scan the underside of the sealed package with a cell phone and determine whether the food is tainted without the need for any further lab testing.

In contrast to today’s frequently broad recalls that end up wasting unspoiled foods, having easy, immediate access to such information would allow public health authorities, producers, and retailers to trace and isolate contamination quickly, reducing the risk of potentially serious infections. This would also significantly reduce food waste by identifying precisely which lots of food need to be recalled and destroyed.

Additionally, the researchers claim that shielding customers from tainted foods will result in significant savings on medical expenses. Every year, there are over 600 million cases of food-borne disease worldwide, which is primarily caused by eating food products that have pathogen contamination.

The McMaster researchers and their associates have been working on analogous technologies for a number of years with the goal of developing straightforward, low-cost methods to stop and identify food poisoning.

Their work is part of McMaster’s broader Global Nexus School for Pandemic Prevention & Response.

Co-author Tohid Didar, an associate professor of mechanical and biomedical engineering who holds the Canada Research Chair in Nano-biomaterials, says package-based sensors that measure other conditions such as humidity are already becoming common in Japan and elsewhere.

He said the McMaster research team on the Lab-in-a-Package project featuring 11 colleagues from the fields of biomedical, mechanical and chemical engineering, medicine, and biochemistry has worked to make the new contamination sensor as adaptable and economical as possible, knowing food producers are under pressure to keep costs low.

“It’s really just a matter of time before technology like this becomes common all over the world,” Didar says. “Now that we’ve shown that one kind of food package can reveal contamination without even being opened, we can adapt it to other forms of packaging for other types of foods.”

Didar and his colleagues Yingfu Li, a professor of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences, and Carlos Filipe, McMaster’s Chair of Chemical Engineering, supervised the research.

“Being able to combine packaging and Salmonella detection in one system is already very promising,” says Li. “It also shows that we can add sensing probes for other food-borne pathogens to the same system so the package will check for all of them at once. That’s the next step for us, and we’re already working on it.”