A new study by economists found that aging populations lead to increased use of robots in the workplace. You might believe that robots and other forms of workplace automation gain traction as a result of inherent technological advances – that innovations naturally find their way into the economy. A study co-authored by an MIT professor, on the other hand, tells a different story: Robots are more widely used in areas where the population is getting older, filling gaps in an aging industrial workforce.

“One of the most important factors leading to the adoption of robotics and other automation technologies is demographic change,” says Daron Acemoglu, an MIT economist and co-author of a new paper detailing the study’s findings.

According to the study, aging alone accounts for 35% of the variation in robot adoption across countries. The research shows the same pattern within the United States: metro areas where the population is aging at a faster rate are the places where industry invests the most in robots.

“We provide a lot of evidence to support the case that this is a causal relationship, and it is driven by exactly the industries that are most affected by aging and have opportunities for automation,” Acemoglu adds.

One of the most important factors leading to the adoption of robotics and other automation technologies is demographic change. The research shows the same pattern within the United States: metro areas where the population is aging at a faster rate are the places where industry invests the most in robots.

Daron Acemoglu

The paper, “Demographics and Automation,” was published online by The Review of Economic Studies and will be printed in the journal’s next print edition. Acemoglu, an Institute Professor at MIT, and Pascual Restrepo, an assistant professor of economics at Boston University, are the authors.

An “amazing frontier,” but driven by labor shortages

The current study is the latest in a series of papers published by Acemoglu and Restrepo on automation, robots, and the workforce. They previously quantified job displacement in the United States as a result of robots, examined the firm-level effects of robot use, and identified the late 1980s as a watershed moment when automation began replacing more jobs than it created.

This research includes multiple layers of demographic, technological, and industry-level data spanning the early 1990s to the mid-2010s. First, Acemoglu and Restrepo discovered a strong relationship between an aging labor force – defined as workers aged 56 and older to those aged 21 to 55 – and robot deployment in 60 countries. According to the researchers, aging alone accounted for not only 35% of the variation in robot use across countries, but also 20% of the variation in robot imports.

Other data points involving specific countries stand out as well. South Korea has been the country with the fastest aging population as well as the most extensive use of robotics. Furthermore, Germany’s relatively older population accounts for 80% of the difference in robot implementation between that country and the United States.

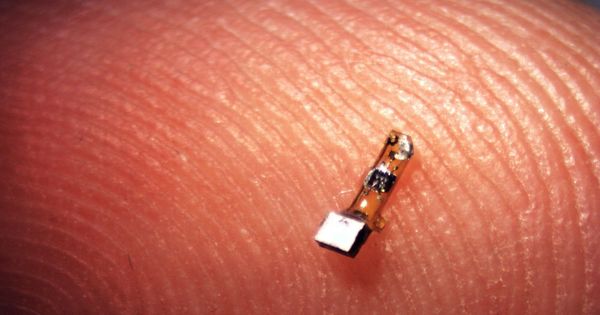

“Our findings suggest that quite a bit of investment in robotics is not driven by the fact that this is the next ‘amazing frontier,’ but because some countries have labor shortages, particularly middle-aged labor that would be required for blue-collar work,” says Acemoglu. Digging into a wide variety of industry-level data across 129 countries, Acemoglu and Restrepo concluded that what holds for robots also applies to other, nonrobotic types of automation.

“When we look at other automation technologies, such as numerically controlled machinery or automated machine tools, we find the same thing,” Acemoglu says. At the same time, he observes, “We do not find similar relationships when we look at nonautomated machineries, such as nonautomated machine tools or things like computers.”

The study will most likely shed light on larger-scale trends as well. Workers in Germany have fared better economically in recent decades than in the United States. According to the current research, there is a distinction between adopting automation in response to labor shortages and adopting automation as a cost-cutting, worker-replacing strategy. Robots have entered the workplace more in Germany to compensate for worker absences; in the United States, relatively more robot adoption has displaced a slightly younger workforce.

“This could explain why South Korea, Japan, and Germany – the world leaders in robot investment and the fastest aging countries – have not seen labor market outcomes [as bad] as those in the United States,” Acemoglu writes.

Back in the U.S.

Acemoglu and Restrepo used the same techniques they used to study demographics and robot usage globally to study automation in the roughly 700 “commuting zones” (essentially, metro areas) in the United States from 1990 to 2015, while controlling for factors such as the industrial composition of the local economy and labor trends.

Overall, the same global trend was observed in the United States: older workforce populations were more likely to adopt robots after 1990. The study discovered that a 10% increase in local population aging resulted in a 6.45% increase in the presence of robot “integrators” in the area – firms that specialize in installing and maintaining industrial robots.

Population and economic statistics from multiple United Nations sources, including UN Comtrade data on international economic activity; technology and industry data from the International Federation of Robotics; and U.S. demographic and economic statistics from multiple government sources were used in the study. Acemoglu and Restrepo studied patent data in addition to their other layers of analysis and discovered a “strong association” between aging and patents in automation, as Acemoglu puts it. “Which makes sense,” he continues.

Acemoglu and Restrepo, for their part, are continuing to investigate the effects of artificial intelligence on the workforce, as well as the relationship between workplace automation and economic inequality. Google, Microsoft, the National Science Foundation, the Sloan Foundation, the Smith Richardson Foundation, and the Toulouse Network on Information Technology all contributed to the study.