Introduction:

Over the past two decades Bangladesh has made impressive gain in key health indicators, which are important to achieve maternal and child health related MDGs 4 and 5 (NIPORT, Mitra and associate, 2009). From 1989 to 2007, maternal mortality ratio (MMR) declined from 650 to 290 per 100,000 live births and under-five child mortality rate (U5MR) dropped from 133 to 65 per 1000 live births. However MMR in Bangladesh is still remarkably high and Bangladesh is still far away from achieving the MDG target of reducing MMR to 143 per 100,000 by the year 2015. Encouragingly, Bangladesh is considered to be on track in reducing child mortality rate but sustaining this rate will demand cautious and continued effort (ICDDR,B 2007). This is also concerned to neonatal mortality rate, which has declined modestly from 52 to 37 per 1000 live births (NIPORT, Mitra and associates and Macro International 2008). Inequalities in terms of socio-economic status and geographic location are major challenges in achieving equitable development in maternal and child health (NIPORT, Mitra and associates and Macro International 2008).

Poor health and malnutrition is the outcome of many complex biological and social processes. The roots of malnutrition run deep into its social soil. One fourth of the non-pregnant mothers living in the slum suffer from severe malnutrition and about 70% of women in Bangladesh suffer from deficiency anaemia (Talukder, 1992; Haque, 1991; Ghani, 1987). The deprivation to women and children is a common picture of Bangladesh. The socio-economic, health and nutritional status of the most vulnerable groups: women and children depict a gloomy picture throughout their lives (Nessa, 1997; Gopalan, 1992).

Bangladesh advanced to a greater extent, in education specially in women education. In health sector, it achieved a great success in some components. Knowledge on ante natal care and routine practice of ante natal check up by the pregnant women has been increased to a greater extent. But still Bangladesh is awaiting routine post natal care. Now a day, maximum women after delivery seek post natal care when there is any complication or problem. To establish routine post natal care for every pregnant woman after delivery, knowledge regarding post natal complication and importance of post natal care of the women and other family members should be increased. The government of Bangladesh and international health agencies are very much concerned about this.

In this study an attempt has been made to explore the actual situation regarding knowledge and attitude towards seeking postpartum care and use of contraceptive by the pregnant women in Thakurgaon Metropolitan area.

Justification of the study Although there has been a tremendous achievement in primary health care (PHC) in Bangladesh, there has been marked failure in some activities, the most gloving being almost no achievement in improvement of nutritional status of the women of reproductive age specially in rural areas, post partum care, etc.. One of the main contributors to this situation is the miserable condition of the women in rural area and urban slum area. For example, 72% of the population is unable to meet the minimum daily requirements of 500 kilojoules and 48 gms. of protein, while 20% of the population has even lower levels energy intake of less than 380 kilojoules (Khan, 1996; WHO, 1995; Wali, 1993).

It is also found that although Bangladesh made an satisfactory gain in maternal health but still post partum care practice is very low and it differs from region to region and different socio-economic status. Only one fifth of the mothers sought post partum care against 50 percent ante natal care. It is also evident that post partum contraceptive method acceptance is very low and most of the mothers do not know about post partum methods.

Agarwal (2005) in his research showed that urban poor population constitutes nearly a third of India’s urban population and is growing at three times the national population growth rate. Health status and access of reproductive and child health services of slum dwellers are poor and comparable to rural people. Naturally similar situation is existing in the urban poor of Thakurgaon City area. So an effort to improve the conditions of mothers and children of Thakurgaon city is obviously necessary.

From the above discussion, it is clear that the research on pregnant mothers of Thakurgaon city, specially on post partum care is very much relevant and deserves in-depth studies. This could help explain many of the inter-related variables which come into play in explaining the prevailing situation in the urban slums.

The purpose of this study is to find out the knowledge and attitude towards seeking post partum care and use of contraceptive during post partum period by the pregnant women in Thakurgaon City area which might provide us and the concern people a comprehensive picture about the said situation and thus help to carry out further in depth study to increase the knowledge and attitude of the pregnant women of Thakurgaon City area towards seeking post natal care.

HypothesesKnowledge and attitude of the pregnant women of Thakurgaon City area towards seeking postpartum care is low.

ObjectivesGeneral objective

The study was done with a view to explore the knowledge and attitude towards seeking postpartum care and use of contraceptives by the pregnant mothers in Thakurgaon.

Specific objectives

(i) To find out knowledge about post partum care after delivery.

(ii) To find out the knowledge about postpartum contraceptive methods after delivery.

(iii) To explore the current attitude towards seeking postpartum care service.

(iv) To explore the knowledge on dangers of not seeking postpartum care by the pregnant women.

(v) To find out the relation between socio-demographic indicators and knowledge of postpartum care and use of contraceptive methods during postpartum period.

Variables used in this study

A. Dependent variable

Attitude towards postpartum care

B. Socio-demographic variables

1. Age of the respondents

2. Education

3. Occupation

4. Husband’s education

5. Husband’s occupation

6. Monthly family income in Taka

6. Total family members

7. Age of last child

8. Religion

9. Type of family

C. Outcome variables

1. Knowledge of postpartum care and service seeking attitude

2. Barriers to seek services from qualified providers

3. Receive quality services from the providers

4. Reasons for not seeking postpartum care from qualified providers

5. Visit urban clinic for receiving postpartum care information and service

6. Knowledge on sources of services

Operational definitions

Type of family

In this study families were classified as follows:

(a) Nuclear family: Parents or parent (either father or mother) with one or more unmarried child(ren).

(b) Extended (Non nuclear) family: Parents or parent with married or never married children with or without other relatives (e.g., father-in-law, mother-in-law, uncle, aunt, etc.) eating from the same kitchen.

Income

Material return in kind or cash in exchange of goods and services earned by the person (respondent) only is known as personal income and by the household members is known as household income. Household income or total family income consists of total income of all the members of the family living in the same household and taking food from the same cooking pot.

Knowledge on postpartum care

As the knowledge of postpartum care, this study includes the days of post partum period, period of seeking care, dangers of post partum period, postpartum contraceptive methods and attitude of the pregnant women.

LITERATURE REVIEW

More than one-quarter of maternal deaths in Egypt occur during the postpartum period—the period following the delivery of the placenta until the forty-second day post delivery. One-third of these postpartum deaths are due to postpartum hemorrhage.1 The Prevention of Maternal Mortality Network developed the “3 Delays Model,” which identifies three delays that can occur in obtaining emergency obstetric care: (1) a delay in deciding to seek care; (2) a delay in reaching a first referral level facility; and (3) a delay in actually receiving care. Best practices in safe motherhood programming have demonstrated the importance of minimizing these three delays. Although major improvements in maternal health have been achieved in Egypt, 30% of all maternal deaths are still attributed to delays in seeking care, while 54% are attributed to substandard care (Tahseen, 2003).

Research conducted by TAHSEEN concluded that lack of postpartum training for physicians and nurses at primary health centers, shortage of nurses (to conduct home visits), women’s lack of knowledge about clinics’ postpartum services including the recommended 40th day clinic visit, and misconceptions (women waiting for return of menses before seeking FP services) and taboos (meeting a woman who menstruates interferes with breastfeeding) were among the major obstacles to providing appropriate PPC. TAHSEEN research also found that few providers offer their postpartum clients family planning counseling or methods. 3 Furthermore, only 3% of women in rural Upper Egypt practice prolonged breastfeeding (Tahseen, 2003).

Most deaths of mothers and newborns occur very soon after delivery – over 60 percent of maternal deaths occur in the first 48 hours after childbirth (WHO 2005). For many women in eastern and southern Africa the postnatal period is a time of increased susceptibility to HIV and STIs (McIntyre 2005; Dept of Health, South Africa 2003). There is also increasing evidence that maternal deaths related to HIV are rising (Gray and McIntyre 2005; Lewis 2004). Three quarters of newborn deaths occur in the first week and of those, two thirds occur in the first 24 hours (Lawn et al 2005). Although HIV infection in the mother will influence the baby‟s survival, practically all neonatal deaths in the first month of life are due to non-HIV causes (e.g. asphyxia, sepsis and prematurity), highlighting the need to address the quality of basic maternal and newborn care. It has been estimated that if 90 percent of babies and mothers received routine postnatal care (PNC) 10 to 27 percent of newborn deaths could be averted (Warren, Daly, Touré and Mongi 2006). Inter-pregnancy intervals of less than 18 months and more than 59 months are significantly associated with increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes (Conde-Agudelo et al 2006). The WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing (WHO, 2005) reported that for the healthiest outcome for mother and baby, couples should wait at least two years after the birth of their last infant before they try to conceive again to reduce risks of adverse maternal, perinatal and infant outcomes (Mwangi, 2008).

The study was conducted in Embu district, Eastern Province, between 2006 and 2008. The study used a pre-post intervention design for assessing quality of care received within the facilities and compared stratified samples of postpartum women recruited and interviewed following childbirth and again six months later before and after introduction of the intervention. For the quality of care assessment, data were collected through interviews with health care providers, structured observations of client – provider interactions during the postnatal consultations and a facility inventory for assessing availability of equipment, drugs, family planning commodities and supplies. Postpartum women were recruited and interviewed following childbirth on the postnatal ward in Embu Provincial General Hospital and interviewed again in their community after six months. A postnatal care – family planning (PNC-FP) orientation package for providers was developed by ACCESS-FP, DRH and FRONTIERS. This incorporated relevant maternal and newborn health care services in the postnatal period with a specific focus on postpartum family planning. Job aids were also produced. The three day orientation training included staff from the maternity and MCH- FP units from the four health facilities, as well as provincial and district RH trainers/supervisors. In total, 73 health care providers were oriented in the PNC – FP package, as well as in the use of a new postnatal register recently released by the MOH. Regular supportive supervision visits were made during the intervention period to reinforce application of the package. The key findings were as follows:

Facilities were prepared or needed minimal adjustments to provide strengthened PNC and postpartum family planning services.

Provider knowledge improved in maternal and newborn care. Providers were more likely to report discussing FP with postpartum women at 48 hours and at six weeks. It is important to note that provider knowledge in several components was weaker than anticipated before the intervention and that although there were significant improvements, gaps remained at end line in that need further attention.

Overall quality of care improved, especially in counseling for family planning and in ensuring the mother had a physical checkup during the 48 hour, two week and six week consultations.

Substantial improvements in uptake of family planning postpartum were noted. Significantly more women were observed accepting an FP method during the six week consultation after the intervention; specifically the IUD and LAM, indictable and female sterilization rates were also higher among the intervention group (although these differences were not statistically significant). Providers are both satisfied and confident with the care they give to postpartum women. Health system gaps and insufficient numbers of health providers that are commonly found throughout Kenya inhibited full implementation of the intervention and were not inherent to the approach itself. Postpartum women are willing to come for the increased number of postnatal checkups and to bring their infants; they were also significantly more likely to recommend the services to a friend. Significantly more women and their infants made their first visit to the PNC within 14 days of delivery after the intervention. Infants are still seen by health providers twice as often as their mothers during the six months postpartum period, suggesting that mothers and providers still perceive PNC as being more important for the infant than the mother. Postpartum women now start using FP methods much earlier (i.e. within two months) after the intervention. This may be attributable to women being more likely to report having been informed about a choice of family planning methods at several times during ANC and through to six months postpartum. After the intervention, there was an increase in the use of FP methods by six months and a decrease in women with an unmet need for family planning, although neither was statistically significant (Mwangi, 2008).

The influence of social support on maternal attitudes and behaviors was assessed in 57 third-trimester adolescent women attending an urban prenatal clinic. Sociodemographic characteristics, social support, self-esteem, and feelings about pregnancy were measured by questionnaire. The support and influence of the adolescent father was emphasized. Social support was measured as a multidimensional construct derived by a priori and empirical procedures. The outcomes measured were the amount of prenatal care, attendance at scheduled postpartum appointments, and pleasure with the pregnancy. Stepwise multiple-regression analyses were used to assess the contributions of the predictor to criterion variables. Pleasure with pregnancy was positively associated with the receipt of assistance from the adolescent’s mother, favorable opinions of friends, and satisfaction with living arrangements. Attendance at postpartum visits was associated with high self-esteem. Notably absent as significant contributors were sociodemographic characteristics, receipt of emotional and tangible support from the adolescent father, and expectation of aid from social-assistance programs (Giblim, 2005).

Observational studies suggest that including men in reproductivehealth interventions can enhance positive health outcomes. Arandomized controlled trial was designed to test the impactof involving male partners in antenatal health education onmaternal health care utilization and birth preparedness in urbanNepal. In total, 442 women seeking antenatal services duringsecond trimester of pregnancy were randomized into three groups:women who received education with their husbands, women whoreceived education alone and women who received no education.The education intervention consisted of two 35-min health educationsessions. Women were followed until after delivery. Women whoreceived education with husbands were more likely to attenda post-partum visit than women who received education alone[RR = 1.25, 95% CI = (1.01, 1.54)] or no education [RR = 1.29,95% CI = (1.04, 1.60)]. Women who received education with theirhusbands were also nearly twice as likely as control group womento report making >3 birth preparations [RR = 1.99, 95% CI= (1.10, 3.59)]. Study groups were similar with respect to attendingthe recommended number of antenatal care checkups, deliveringin a health institution or having a skilled provider at birth.These data provide evidence that educating pregnant women andtheir male partners yields a greater net impact on maternalhealth behaviors compared with educating women alone (Mullany, 2007).

METHODOLOGY

Where:

n = Sample size estimate

Z = Z for level of significance alpha (at 0.05 level of significance value of Z is 1.96)

p= 50%

q= 1-p

d= acceptable margin of error (0.10)

Actual sample size was= 1.96 x 1.96x 0.5×0.5/0.1×0.10

= 96.04 @ 100

Sampling technique: Purposive sampling technique was followed.

Data collection instruments: A partially structured questionnaire which was duly pre-tested, was used to collect data from the respondents.

Data collection procedure: The researcher targeted those pregnant ladies who attended clinics and Gynae OPD of Thakurgaon Medical College Hospital for data collection. Data were collected through a partially structured questionnaire. Baseline information on socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitude and practice with respect to postpartum care was collected from study participants through interviewer administered questionnaire by face to face interview. All efforts were made to collect data accurately. For open questions, the respondents were asked in such a manner so that they could speak freely and explain their opinion in a normal and neutral way. No leading questions were asked.

Inclusion criteria of the respondents:

Pregnant women any health clinic or Gynae & Obs OPD of Thakurgaon Medical College Hospital for health information and services for ANC.

Living in Thakurgaon City

Exclusion criteria:

- Unwilling to participate in the study.

Data analysis: After proper verification, data were coded and entered into the computer by using SPSS/PC programme. Data were analyzed according to the objectives of the study by using SPSS/PC+ software computer programme. Descriptive variables were explained with mean and standard deviation. Statistical significance was found by applying relevant statistical tests at appropriate probability level (p ═ 0.05 or p=0.01).

Ethical consideration: Prior to the commencement of the study, the research protocol will be approved by the research committee (Local ethical committee). The aim and objectives of the study along with its procedure, risks and benefits of the study will be explained to the respondents in easily understandable language and then informed consent will be taken from each participant. Then it was assured that all information and records will be kept confidential and the procedure will be used only for research purpose and the findings will be helpful for developing awareness package to increase awareness and to improve service seeking behaviour of the women in Bangladesh.

RESULTS

Table 1: Distribution of the respondents by their age (n=100)

Age group in years | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| 15 – 19 years20 – 24 years25 – 29 years 30 – 34 years 35 years & above | 02 27 30 18 23 | 02 27 30 18 23 |

X ± SD = 28.6 ± 6.3 years

Table 1 showed that the maximum respondents (30%) were in the age group of 25 to 29 years followed by 27%, 23%, 18% and 02% in the age groups of 20 to 24 years, 35 years and above, 30 to 34 years and 15 to 19 years respectively. The mean age of the respondents was 28.6 (± 6.3) years.

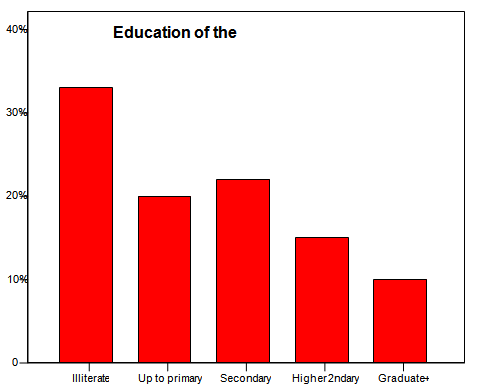

Figure : Distribution of the respondents by educational status

Figure 1 showed that majority of the respondents (33%) were illiterate. Twenty percent of them had primary education, 22% had education up to secondary level and 15% had higher secondary level education. Only 10% of them were graduates or masters.

Table 2: Distribution of the respondents by their occupation (n=100)

Occupation of the respondents | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| House wifeService holders / TeachersDay labour Others | 53 29 06 12 | 53 29 06 12 |

A larger proportion of the respondents (53%) were house wives. Among other occupations, 29% of them were service holders, 6% were day labours i.e.; who lead their lives by daily earning and 12% had miscellaneous occupations.

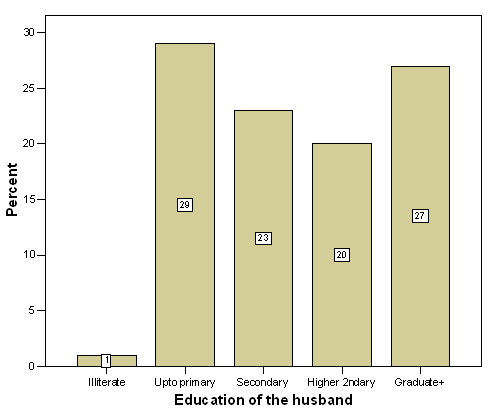

Figure : Distribution of the respondents by their husbands’ education

About 27% of the respondents’ husbands were graduates or master degree holders. Twenty percent of them had higher secondary level education, 23% had secondary level and 29% had primary level education. Very negligible number (!%) was illiterate.

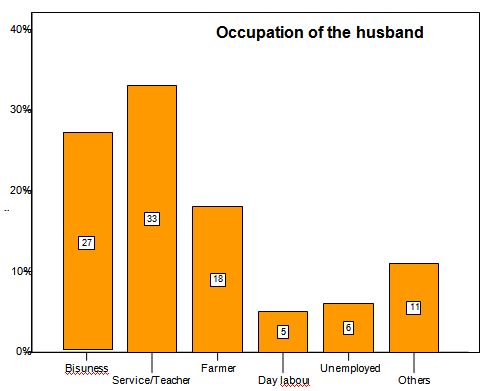

Figure : Distribution of the respondents by their husbands’ occupation.

Figure 3 showed that majority of the respondents’ husbands (33%) were service holders, followed by businessmen (27%), farmers (18%), unemployed (6%), day labourers (5%) and others (11%).

Table 3: Distribution of the respondents by monthly family income (n=100)

Monthly income of the family | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Taka up to 6000 | ||

Taka 6001 – 12000

Taka 12001 – 18000

Taka > 18000

45

33

18

04

45

33

18

04

X ± SD = Taka 9480.00 ± 5774.00

Majority (45%) of the respondents’ monthly family income was Taka 6000 or less than that, 33% of them had monthly family income of Taka 6001 to 12000, 18% had Taka 12001 to 18000 and only 4% had monthly family income of Taka more than 18000. The mean monthly family income was Taka 9480.00 (± 5774).

Table 4: Distribution of the respondents by family type (n=100)

Type of family | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Nuclear | ||

Non-nuclear

60

40

60

40

Sixty percent of the respondents was from nuclear family and rest (40%) was from non-nuclear family.

Table 5: Distribution of the respondents by religion (n=100)

Religion of the respondents | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Islam | ||

Hindu

80

20

80

20

Table 5 showed that 80% of the respondents were from Muslim family and 20% was from Hindu family.

Table 6: Distribution of the respondents by the number of their children (n=100)

No. of children | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| No child | ||

Single child

2 children

3 children

5 children

38

35

21

05

01

38

35

21

05

01

X ± SD = 0.97 ± 0.97

Thirty eight percent of the respondents had no child at all at the time of survey, 35% of them had single child, 21% had two children, 5% had three children and only one (1%) had five children.

Table 7: Distribution of the respondents by the age of last child (n=100)

Age of last child | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| No child | ||

0 – 1 year

1 – 5 years

>5 years

38

00

50

12

38

00

50

12

X ± SD = 2.8 ± 3.8 years

Only 62% of the respondents had child and among those who had child, none of them had infant, 50% of the respondents had last child whose age was between 1 to 5 years and age of the last child was more than 5 years of 12% responding mothers. The mean age of the last child was 2.8 (± 3.8) years.

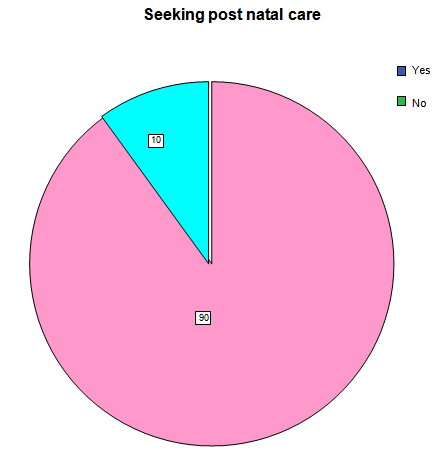

Figure 4: Distribution of the respondents by the concept of seeking post natal care from doctors.

Figure 4 showed that most of the respondents (90%) thought that women should seek advice from doctors during postpartum period and only 20% of the respondents did not think so.

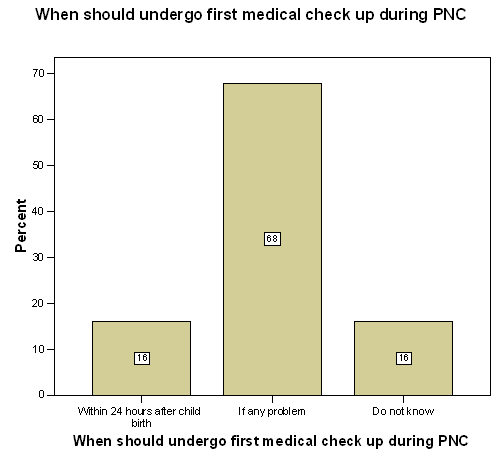

Figure : Knowledge on first medical check up during post partum period

The above figure showed that majority of the respondents (68%) proposed that a woman should undergo first medical check up only then when she had any problem or faced any complication, 16% of them thought that a woman should undergo first medical check up within 24 hours after child birth whether she had any problem or not and 16% confessed that they had no idea about the matter.

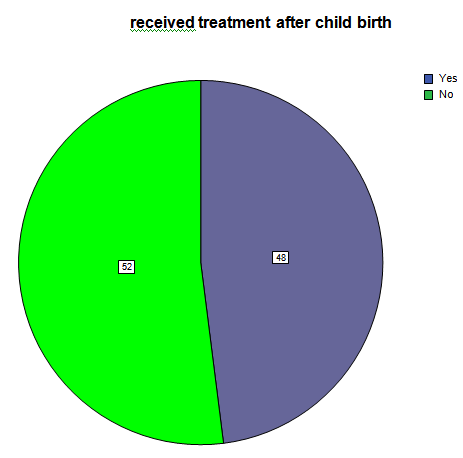

Figure : Treatment received after last child birth

In reply to a question whether she received treatment after last child birth, 48% of the respondents told that they received treatment and 52% told that they did not receive treatment after last child birth.

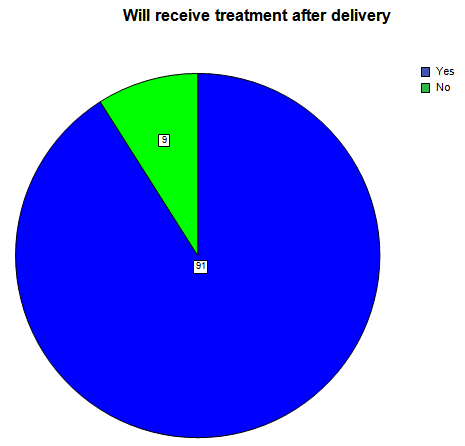

Figure : Concept regarding post natal care after next delivery

From the above figure it is clear that 91% of the respondents possessed desire to receive treatment after next delivery and only 9% of them did not possess desire to receive treatment after next delivery.

Table 8: Distribution of the respondents by their concept regarding time of treatment after delivery (n=100)

Time of treatment after delivery | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Within 24 hours | ||

If any problem

Do not know

15

67

18

15

67

18

Most of the respondents (67%) were in favour of treatment after delivery when there was any problem or complication, 15% of the respondents were in favour of treatment within 24 hours of delivery without concerning any problem and 18% told that they had no idea about this matter.

Table 9: Distribution of the respondents by the type of conducting physician (n=100)

Type of conducting physician | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| MBBS doctor | ||

Specialist

Homeopathy

Kabiraj

No treatment

Others

50

25

11

04

05

05

50

25

11

04

05

05

A half of the respondents (50%) opined that they will conduct MBBS doctor during post natal period, 25% will conduct specialist, 11% homeopathy and 5% of them will not conduct any physician.

Table 10: Distribution of the respondents by place of PNC (n=100)

Place of PNC | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Doctor’s chamber | ||

Hospital

Govt. health centre

Private clinic

No treatment

Others

13

55

04

05

07

16

13

55

04

05

07

16

Maximum respondents (55%) wished to receive treatment during post partum period from hospitals, 13% liked to receive post natal care from doctors’ chambers, 4% from government health centre and 5% from private clinics.

Table 11: Distribution of the respondents by taking initiative for PNC (n=100)

Person taking initiative for PNC | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Self | ||

Husband

Parents-in-law

No treatment

Relative

18

57

02

11

12

18

57

02

11

12

Table 11 showed that the husbands of the maximum respondents (57%) took initiative for post natal care (PNC) during last post partum period, 18% of the respondents themselves took initiative for PNC, which indicates the consciousness of the respondents about health of themselves and their offspring.

Table 12: Distribution of the respondents by the accompanying persons to health centre (n=100)

Accompanying persons | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Alone | ||

Husband

Children

Relatives

No need

Others

12

59

00

17

07

05

12

59

00

17

07

05

Maximum respondents (59%) went to doctor’s chamber or any health centre along with their husbands, some of them (12%) went alone to doctor’s chamber or health centre. A remarkable number of respondents (17%) went to health centre or doctor’s chamber accompanied by their relatives.

Table 13: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge on potential risks to women after delivery (n=100)

Potential risks after delivery | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Bleeding | ||

Infection

Breast abscess

Multiple

Others

53

05

01

06

35

53

05

01

06

35

Maximum respondents had partial knowledge on potential risks to women after delivery. Post partum haemorrhage (PPH) is one of the common complication after delivery, which is told by 53% of the respondents but none of them told about another common complication i.e.; infection (puerperal sepsis).

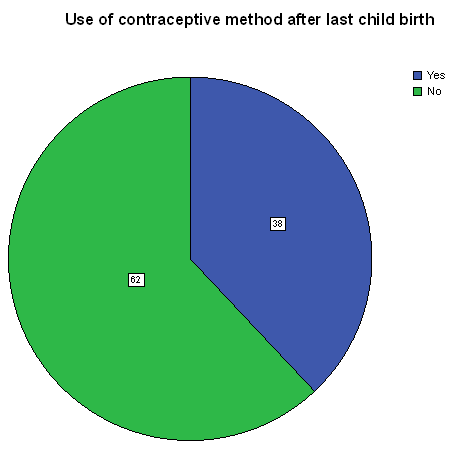

Figure 8: Distribution of the respondents by use of contraceptive methods after last child birth

This figure showed that 38% of the respondents used contraceptive after last child birth and 62% of them did not use any contraceptive after last child birth.

Table 14: Distribution of the respondents by use of contraceptive in future (n=100)

Willingness of use of Contraceptive in future | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Yes | ||

No

82

18

82

18

Eighty two percent of the respondents desired to use contraceptive in future and only 18% of them did not desire to use of contraceptive in future.

Table 15: Distribution of the respondents by the choice of contraceptive method for use in future (n=100)

Contraceptive methods | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Oral pill | ||

IUCD

Injection

Condom

Permanent method

No method

41

00

13

04

18

24

41

00

13

04

18

24

Maximum respondents (41%) expressed their willingness to use oral pill as contraceptive in future, 18% for permanent methods, 13% for injection and 4% for condom but none of them expressed desire for Cu-T (IUCD).

Table 16: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge about place of getting contraceptive (n=100)

Knowledge about place of getting contraceptive | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| Yes | ||

No

74

26

74

26

Maximum respondents (74%) knew the place from where she would collect contraceptive method and 26% of them did not know that.

Table 17: Distribution of the respondents by contraceptive collection pattern, n=100

Collection of contraceptive method from | Respondents | |

No. | % | |

| FWA | ||

FWV

Shop

Hospital

UHC

Do not know

Others

05

07

03

20

28

18

19

05

07

03

20

28

18

19

Many of the respondents collect contraceptive methods from different health institutes or health centres (20% from hospitals & 28% from Upazilla Health Complex). Some of them (5%) collect from FWA, 7% from FWV, 18% do not know & 19% from others.

Table 18: Relationship between educational status of the respondents and seeking behaviour of post natal care (n=100)

Educational status of the respondents | Seeking post natal care | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Illiterate | |||

Up to primary

Secondary

Higher secondary

Graduate+28 (84.8)

16 (80)

22 (100)

14 (93.3)

10 (100)05 (15.2)

04 (20)

00 (00)

01 (6.7)

00 (00)33 (33)

20 (20)

22 (22)

15 (15)

10 (10)Total90 (90)10 (10)100 (100)

χ2 = 6.93, df = 4, p > .05

From the above table it was found that the educated respondents were a little bit more conscious about seeking post natal care than illiterate or less educated respondents. But the difference was not statistically significant (p>.05).

Table 19: Relationship between educational status of the respondents’ husbands and seeking behaviour of post natal care of the respondents (n=100)

Educational status of the respondents’ husbands | Seeking post natal care | Total | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Illiterate | |||

Up to primary

Secondary

Higher secondary

Graduate+01 (100)

22 (75.9)

21 (91.3)

19 (95.0)

27 (100)00 (00)

07 (24.1)

02 (8.7)

01 (5)

00 (00)01 (01)

29 (29)

23 (23)

20 (20)

27 (27)Total90 (90)10 (10)100 (100)

χ2 = 10.15, df = 4, p < .05

Only one respondent’s husband was illiterate. If he was excluded from count, it was found that post partum care seeking behaviour of the respondents was gradually more with the increase of their husbands’ educational status and the association was statistically significant (p<.05).

Table 20: Relationship between monthly family income of the respondents and seeking behaviour of post natal care (n=100)

Monthly family income | Seeking post natal care | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Taka up to 6000 | |||

Taka 6001 – 12000

Taka 12001 – 18000

Taka >1800037 (82.2)

31 (93.9)

18 (100)

04 (100)08 (17.8)

02 (6.1)

00 (00)

00 (00)45 (45)

33 (33)

18 (18)

04 (04)Total90 (90)10 (10)100 (100)

χ2 = 6.03, df = 3, p > .05

From the above table, it was found that cent percent respondents in the rich and upper middle class group seek post natal care, whereas it was 93.9% in the lower middle class and 82.2% in the poor class. But statistically the difference was not significant (p>.05).

Table 21: Relationship between educational status of the respondents’ husbands and treatment after child birth (n=100)

Educational status of the respondents’ husbands | Treatment after child birth | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Illiterate | |||

Up to primary

Secondary

Higher secondary

Graduate+00 (00)

06 (20.7)

06 (26.1)

15 (75)

21 (77.8)01 (100)

23 (79.3)

17 (73.9)

05(25)

06 (22.2)01 (01)

29 (29)

23 (23)

20 (20)

27 (27)Total48 (48)52 (52)100 (100)

χ2 = 29.44, df = 4, p < .001

About 78% of the respondents received treatment whose husbands were graduates, 75% got treatment whose husbands had higher secondary education, 26% whose husbands had secondary education and only 20.7% whose husbands had primary education. Treatment of the respondents after child birth was directly related to the educational status of the respondents’ husbands and that was statistically significant (p<.001).

Table 22: Relationship between educational status of the respondents and treatment after child birth (n=100)

Educational status of the respondents | Treatment after child birth | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Illiterate | |||

Up to primary

Secondary

Higher secondary

Graduate+10 (30.3)

04 (20)

16 (72.7)

11 (73.3)

07 (70)23 (69.7)

16 (80)

06 (27.3)

04(26.7)

03 (30)33 (33)

20 (20)

22 (22)

15 (15)

10 (10)Total48 (48)52 (52)100 (100)

χ2 = 21.60, df = 4, p < .001

The educational status of the respondents was inversely related to their treatment after child birth. The percentage of the respondents receiving treatment was more among those who were highly educated whereas that percentage was very low among illiterate respondents and the difference was statistically significant (p<.001).

Table 23: Relationship between monthly family income of the respondents and treatment after child birth (n=100)

Monthly family income | Treatment after child birth | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Taka up to 6000 | |||

Taka 6001 – 12000

Taka 12001 – 18000

Taka > 1800009 (20)

23 (69.7)

12 (66.7)

04 (100)36 (80)

10 (30.3)

06 (33.3)

00(00)45 (45)

33 (33)

18 (18)

04 (04)Total48 (48)52 (52)100 (100)

χ2 = 27.20, df = 3, p < .001

Cent percent of the respondents who were rich, received treatment after child birth, 66.7% took treatment who was upper middle class, 69.7% were lower middle class and 20% were poor who received treatment. So treatment of the respondents after child birth was inversely related to monthly family income which was statistically significant (p<.001).

Table 24: Relationship between educational status of the respondents and knowledge on availability of contraceptive methods (n=100)

Educational status of the respondents | Knowledge on availability of contraceptive method | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Illiterate | |||

Up to primary

Secondary

Higher secondary

Graduate+17 (51.5)

12 (60)

20 (90.9)

15 (100)

10 (100)16 (48.5)

08 (400)

02 (09.1)

00(00)

00 (00)33 (33)

20 (20)

22 (22)

15 (15)

10 (10)Total48 (48)52 (52)100 (100)

χ2 = 22.76, df = 4, p < .001

The table 24 showed that knowledge of the respondents on availability of contraceptive methods was directly related to their educational status which was statistically significant (p<.001).

Table 25: Relationship between occupation of the respondents and knowledge on availability of contraceptive methods (n=100)

Occupation of the respondents | Knowledge on availability of contraceptive methods | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| House wife | |||

Service / Teacher

Day labourer

Others35 (66)

28 (96.6)

03 (50)

08 (66.7)18 (34)

01 (3.4)

03 (50)

04(33.3)53 (53)

29 (29)

06 (06)

12 (12)Total74 (74)26 (26)100 (100)

χ2 = 11.54, df = 3, p < .01

The knowledge on availability of contraceptive methods was more among the service holders or teachers (96.7%) then among the house wives (66%) and lowest among day labourers (50%) and the difference was statistically significant (p<.01).

Table 26: Relationship between monthly family income of the respondents and knowledge on availability of contraceptive methods (n=100)

Monthly family income of the respondents | Knowledge on availability of contraceptive methods | Total No. (%) | |

Yes No. (%) | No No. (%) | ||

| Taka up to 6000 | |||

Taka 6001 – 12000

Taka 12001 – 18000

Taka >1800023 (51.1)

29 (87.9)

18 (100)

04 (100)22 (48.9)

04 (12.1)

00 (00)

00(00)45 (45)

33 (33)

18 (18)

04 (04)Total74 (74)26 (26)100 (100)

χ2 = 23.28, df = 3, p < .001

Cent percent respondents who were rich (monthly income more than Taka 18000) and upper middle class (income Taka 12001 to 18000) knew from where they would get contraceptive methods, 87.9% of lower middle class knew and 51.1% of poor knew from where they would get contraceptive methods and that was statistically significant (p<.001).

DISCUSSION

This cross sectional study provided vivid a clear information about knowledge and attitude of the pregnant women regarding seeking post partum care. This study was carried out among the pregnant women of Thakurgaon City area who attended a clinic or gynae and obs out patient department of Thakurgaon Medical College Hospital for information or service.

In this study the mean age of the respondents was 28.6 years and maximum (30%) of them were in the age group of 25 to 29 years. Majority of the respondents were illiterate but their husbands were literate and 27% of their husbands were highly educated. Maximum respondents (53%) were house wives but a countable number of them (29%) were service holders. Mean monthly family income of the respondents was Taka 9480 and majority (33%) were from lower middle class i.e.; whose income was Taka from 6001 to 12000 only. Most of the respondents (80%) were Muslims and majority (60%) came from nuclear families.

Ninety percent of the respondents seek post natal care after child birth but majority of them (68%) were in favour of visit to doctors if any problem arise during post partum period. Among the respondents, only 52% received treatment after last child birth but when they were asked for post natal care after next delivery, 91% of them gave positive answer. But majority of them (67%) were in favour of treatment if there was any problem. A large proportion of the respondents (55%) wanted post natal care from govt. hospitals. There was good information that 57% of the respondents’ husbands took initiative for post natal care. Similarly 59% of the respondents’ husbands accompanied their wives to health centre for post natal care. Most of the respondents had poor knowledge regarding potential risks to women after delivery. Only 38% of the respondents used contraceptive methods after last child birth but they were asked regarding use of contraceptive method in future, 82% respondents gave positive answer and majority (41%) choose oral pill as contraceptive.

In a study (Hasan, 2002) it was found that on average the respondents were married for 11 years and had four living children. Almost half of them had no antenatal care in their last pregnancy and 75% delivered at home. The findings indicate a poor knowledge of common and serious pregnancy related complications based on their perception related to danger signs. Five percent of the women perceived absent/decreased fetal movement as a danger sign of pregnancy. Other reported danger signs included premature uterine contraction by 3%, premature rupture of membranes by 3%, convulsions by 13%, obstructed labor by 23% and bleeding by 39%. Moreover, the women’s perception regarding obstetric care suggests that unsafe practices prevail: 86% of women thought that a case of ante-partum hemorrhage should be examined internally and 50% thought that no precaution is required to sterilize the instrument for cuffing the cord.

Seeking behaviour of post natal care was not found significantly associated with educational status of the respondents (p>.05) but it was found significantly associated with educational status respondents’ husbands (p<.05) which may be due to husband’s dominancy in decision making process. Educational status of the respondents, that of their husbands and monthly family income were found associated with receiving treatment after last child birth which were statistically highly significant (p<.001). Similarly knowledge of the respondents on availability of contraceptive methods was found positively associated with education, occupation and monthly family income of the respondents and all these were statistically significant (p<.05, p<.01, p<.001).

In a study it was found that 75.8% of the respondents visited an MBBS doctor during their illness (Haque, 2008). In this study it was also found that 75% of the respondents, who received post natal care visited qualified doctors.

In another study (BMMS, 2007), the author observed the knowledge of the pregnant women regarding post natal complications. Overall, women’s awareness of life-threatening complications during pregnancy, delivery and the postpartum period was quite low. Fifty-six percent of women cited tetanus and 49% cited prolonged or obstructed labour as potentially life-threatening conditions, while smaller proportions mentioned retained placenta (38%) or malpresentation of the foetus (25%). Although convulsions and excessive bleeding account for more than half of all maternal deaths in Bangladesh, only 26% and 18% of women, respectively, cited these complications. In all, 89% of surveyed women were able to name at least one obstetric complication, and 42% could name three or more.

The occurrence of at least one complication was reported in six of 10 live births and stillbirths. In 46% of these pregnancy outcomes, one or more complications occurred during gestation; in 35%, during delivery; and in 24%, after delivery. Convulsions and excessive bleeding, the two most important causes of maternal death, were reported in 5% and 13% of cases, respectively. As would be expected, the prevalence of specific complications varied by stage of pregnancy. For the period immediately following delivery, excessive bleeding (10%) and preeclampsia (8%) were the complications cited by the respondents.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion:

This study provided a wide range of information on the knowledge and attitude towards seeking postpartum care by the pregnant women in Thakurgaon. Though this was a cross-sectional study, yet this work strived to depict a comprehensive picture on seeking behaviour of postpartum care which is very much important to improve the health of the women. A total of 100 pregnant women were interviewed. Majority of them were illiterate and house wives. The average monthly income of the family was Taka 9480. Most of the respondents (60%) possessed nuclear family and were Muslims (80%). Maximum respondents (68%) were in favour of seeking care during post natal period if there was any problem and a few of them were in favour of routine visit for care. Seeking behaviour of post natal care was found associated with education, occupation, husbands’ education, monthly family income of the respondents and most of these were found statistically significant. Post partum contraception is an important factor in MCH care. In this study the responding women have poor and partial knowledge regarding potential risk to women after delivery.

From the information we gathered, we come to a conclusion that the existence situation of the post partum care and the knowledge and attitude of the pregnant women towards seeking postpartum care was not satisfactory. But the situation can be improved by providing health education programme specially on postpartum care and postpartum complications in the out patient departments of clinics and hospitals to the mothers who come for information and services. The govt. of Bangladesh can invite NGOs in this sector to gear up the programme.

Recommendations:

The following recommendations might be made on the basis of the study findings:

- At the grass root level all the pregnant mothers should be informed about prevailing care facilities in their locality by the health workers.

- The pregnant mothers should be motivated for maximum utilization of health care facilities by improving their health care seeking bahaviour.

- Post natal complications could be minimized to a greater extent by providing health education to the pregnant mothers regarding personal hygiene and sanitation and by improving their seeking behaviour of post natal care.

- In this regard the government should involve non government organizations who are working in the sectors to make the programme successful.

REFERENCES:

Agarwal, S and Sankar, K 2005, ‘Need for dedicated focus on urban health within National Rural Health mission’, Indian J of Public Health, vol.49, no.3, pp.141-151.

BBS, Bangaldesh Bureau of Statistics 2007. Population census 2001, National Report. Dhaka, Bangladesh.

BMMS, 2007, ‘Maternal health and care seeking behaviour in Bangladesh: findings from a national survey’, International Family Planning Perspective, vol.33, no.2, pp.75-82.

Ghani, AKMA Chowdhury, MMH 1987, ‘Nutrition and fertility’, Bangladesh Journal of Nutrition, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 81-89.

Giblim PT, Poland ML, Sachs BA 2005, ‘Effect of Social Support in Attitudes and Behaviours of Pregnant Adolescent’, Journal of Adolescent Health Care, vol.8, no.3, pp.273-279.

Haque, MJ 2008, ‘Food Habit, Nutritional Status and Disease Pattern of the Dwellers in Slum Environment’, Institute of Environmental Science (IES), Thakurgaon University. PhD Thesis. pp. 135.

Haque, M ed. 1991, Near Miracle in Bangladesh. UNICEF. Dhaka.

Hasan, IJ Nisar, N 2002, ‘Womens’ Perceptions regarding Obstetric Complications and Care in a Poor Fishing Community in Karachi’, Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, vol. 52, pp. 147-149.

Khan, AU and Uddin, KMF 1996, Urban poor in Bangladesh. Centre for urban studies. Dhaka University, Dhaka.

Mullany BC, Becker S and Hindin MJ 2007, ‘The Impact of Including Husbands in Antenatal Health Education Services on Maternal Health practices in Urban Nepal: Results from a RCT’, Health Education Research, vol.22, no.2, pp.166-176.

Mwangi A and Warren C 2008, Strengthening Postnatal Care Services Including Postnatal Family Planning in Kenya’, Frontiers in Reproductive Health & Population Council, June 2008, pp.1-48.

Nessa, N and Mannan, MA 1997, ‘Situation of Women in Bangladesh: their health and nutritional status and support to breast feeding’ (abs.), Nutrition Society of Bangladesh. 7th Bangladesh Nutrition Conference (special publication), p.89.

NIPORT, National Institute of Population and Training, Mitra and Associates and ORC Macro 2009, ‘Bangladesh Demographic and Health survey 2007. Dhaka, Bangladesh’, NIPORT, Mitra and Associates and Calverton, Maryland, USA: ORC Macro.

Tahseen 2003, ‘Best Practices in Egypt: Integrated Community Based Postpartum Care’, Situation Analysis of Postpartum Health Services in Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population Facilities in 2003, Egypt, pp.3-9.

Talukder, MQK and Hasan MQ 1992, ‘Maternal nutrition and Breast feeding’, Bangladesh Journal of Child Health, vol. 16, no. ¾, pp. 95-98.

Wali, A 1993, ‘ The Nutritional Status of Couples of Reproductive Age in Slum of Dhaka’, In Touch, vol.12, no.117, pp.5-6.

WHO, 1995, ‘Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry’, WHO Tech Rep, Series 854, WHO, Geneva.

ANNEXURE

I. Questionnaire

II. Informed Consent Form

III. Thakurgaon City Corporation (RCC) Map

Questionnaire

Title: Attitude Towards Seeking Postpartum Care and Contraceptive by the Pregnant women: An Exploratory Study in Thakurgaon.

Socio-demographic variables:

1. Name : ___________________________________________

2. Age : _________________________________ years

3.Address : Vill/Moholla: _________________, Union: ____________________,

Thana: ___________________, Dist.: __________________________

4. Educational status:

| 1. Illiterate | 2. Upto primary | 3. Secondary | 4. Higher 2ndary | 5. Graduate+ |

5. Occupation :

| 1. House wife | 2. Service/Teacher | 3. Business | 4. Day labour | 5. Others —- |

6. Educational status of husband:

| 1. Illiterate | 2. Upto primary | 3. Secondary | 4. Higher 2ndary | 5. Graduate+ |

7. Occupation of your husband :

| 1. Business | 2. Service/Teacher | 3. Farmer | 4. Day labour | 5. Unemployed | 6. others — |

8. Monthly family income in Taka:

| 1. ≤ 6000 (poor) | 2. 6001-12000 |

(Lower middle class)3. 12001 – 18000

(Upper middle class)4. > 18000 (upper)

9. Type of family :

| 1. Nuclear | 2. Non-nuclear |

10. Religion:

| 1. Islam | 2. Hindu | 3. Christian | 4. Others ———- |

11. How many children do you have at present:

| 1. No child | 2. Total ———–, son ————, daughter ———– |

12. Age of last child, if any:

| 1. No child | 2. ————- years |

13. Do you think that a woman should seek advice from a doctor during postpartum period :

| 1. Yes | 2. No |

14. When she should undergo first medical check up :

| 1. Within 24 hours after child birth | 2. If any problem / complication arises | 3. Do not know |

15. Did you receive treatment after your child birth:

| 1. Yes | 2. No |

16. Will you receive PNC after delivery :

| 1. Yes | 2. No |

17. When will you receive treatment after delivery :

| 1. Within 24 hours after delivery | 2. If any problem arises | 3. Do not know |

18. Who will be your physician after child birth:

1. MBBS doctor 2. Consultant / Specialist

3. Homeo 4. Kabiraj

5. No treatment 6. Others —————————————-

19. From where will you receive treatment:

| 1. Doctor’s chamber | 2. Hospital | 3. Govt. health centre |

| 4. Private clinic | 5. No treatment | 6. Others ——————- |

20. Who took initiative for such treatment during last PNC:

| 1. Myself | 2. Husband | 3. Parents in low | 4. No treatment | 5. Relatives |

21. Who accompanied you to health centre / doctor’s chember:

| 1. Alone | 2. Husband | 3. Children |

| 4. relatives | 5. None | 6. Others ——————- |

22. What are the potential risks to women after delivery:

1. Bleeding 2. Infection 3. Life in danger 4. Breast pain / abscess 5. UTI 6. Convulsion 7. Others ———————————–

23. Did you receive any contraceptive method after your last child birth:

| 1. Yes | 2. No |

24. Will you receive any contraceptive method after delivery):

| 1. Yes | 2. No |

25. What type of contraceptive method will you receive :

| 1.Oral pill | 2. IUCD | 3. Injection |

| 4. Condom | 5. Permanent method | 6. No method |

26. Whose opinion regarding contraceptive method will be preferred:

| 1. Doctor | 2. Husband | 3. Myself | 4. Do not know |

27. Do you know from where you will get contraceptive method :

| 1. Yes | 2. No |

28. From where you will get contraceptive method :

| 1. FWA | 2. FWV | 3. Shop | 4. Hospital |

| 5. UHC | 6. NGO clinic | 7. Do not know | 8. Others ———- |