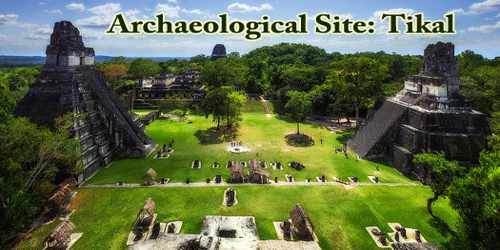

Tikal (/tiˈkɑːl/) (Tik’al in modern Mayan orthography) city and ceremonial centre of the ancient Maya civilization, which was likely to have been called Yax Mutal (meaning “First Mutal”), found in a rainforest in Guatemala. It is one of the largest archaeological sites and urban centers of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is located in the archaeological region of the Petén Basin in what is now northern Guatemala. Situated in the department of El Petén, the site is part of Guatemala’s Tikal National Park and in 1979 it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Historians believe the more than 3,000 structures on the site are the remains of a Mayan city called Yax Mutal, which was the capital of one of the most powerful kingdoms of the ancient empire. Some of the buildings at Tikal date to the fourth century B.C.

The largest urban centre in the southern Maya lowlands, it stood 19 miles (30 km) north of Lake Petén Itzá in what is now the northern part of the region of Petén, Guatemala, in a tropical rainforest. Uaxactún, a smaller Maya city, was located about 12 miles (20 km) to the north.

The name Tikal may be derived from ti ak’al in the Yucatec Maya language; it is said to be a relatively modern name meaning “at the waterhole”. The name was apparently applied to one of the site’s ancient reservoirs by hunters and travelers in the region. It has alternatively been interpreted as meaning “the place of the voices” in the Itza Maya language.

Tikal was the capital of a conquest state that became one of the most powerful kingdoms of the ancient Maya. Though monumental architecture at the site dates back as far as the 4th century BCE, Tikal reached its apogee during the Classic Period, c. 200 to 900 CE. During this time, the city dominated much of the Maya region politically, economically, and militarily, while interacting with areas throughout Mesoamerica such as the great metropolis of Teotihuacan in the distant Valley of Mexico. There is evidence that Tikal was conquered by Teotihuacan in the 4th century CE. Following the end of the Late Classic Period, no new major monuments were built at Tikal and there is evidence that elite palaces were burned. These events were coupled with a gradual population decline, culminating with the site’s abandonment by the end of the 10th century.

Historians believe that people lived at Tikal as far back as 1000 B.C. Archeologists have found evidence of agricultural activity at the site dating to that time, as well as remnants of ceramics dating to 700 B.C.

By 300 B.C., major construction of the city of Yax Mutal had already been completed, including several large Mayan pyramid-style temples.

Starting in the first century A.D., the city began to flourish culturally and politically, overtaking the city of El Mirador to the north in terms of power and influence within the Mayan empire, which stretched as far north as the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. Archeologists have discovered evidence of burials of notable Mayan leaders dating to this time at Tikal.

However, came in the Late Classic Period (600-900 CE), with the planning and construction of its great plazas, pyramids, and palaces, the appearance of Maya hieroglyphic writing and complex systems of time-counting, and the flowering of Maya art as seen in monumental sculpture and vase painting. The numerous dedicatory stelae at the site date from the 3rd century CE until the close of the 9th century. Such stelae, usually bearing the carved features of a priest or other important person, are inscribed with hieroglyphs and dates.

Dynastic rulership among the lowland Maya is most deeply rooted at Tikal. According to later hieroglyphic records, the dynasty was founded by Yax Ehb Xook, perhaps in the 1st century AD. At the beginning of the Early Classic, power in the Maya region was concentrated at Tikal and Calakmul, in the core of the Maya heartland.

Tikal may have benefited from the collapse of the large Preclassic states such as El Mirador. In the Early Classic Tikal rapidly developed into the most dynamic city in the Maya region, stimulating the development of other nearby Maya cities.

The site, however, was often at war and inscriptions tell of alliances and conflict with other Maya states, including Uaxactun, Caracol, Naranjo and Calakmul. The site was defeated at the end of the Early Classic by Caracol, which rose to take Tikal’s place as the paramount center in the southern Maya lowlands. The earlier part of the Early Classic saw hostilities between Tikal and its neighbor Uaxactun, with Uaxactun recording the capture of prisoners from Tikal.

There appears to have been a breakdown in the male succession by AD 317, when Lady Unen Bahlam conducted a katun-ending ceremony, apparently as queen of the city.

Between 600 and 800, Tikal reached its architectural and artistic peak, after which a decline set in, with depopulation and a general artistic deterioration. The last dated stela at the site is placed at 889. Small groups continued to live at the site for another century or so, but Tikal, along with the other Maya centres of the southern lowlands, was abandoned by the 10th century.

By 900 A.D., the city, like much of the Mayan empire, was in sharp decline. Decades of constant warfare started to take their toll. In addition, at around this time, historians believe the region fell victim to a series of droughts and outbreaks of epidemic diseases. This period is known as the collapse of Classic Maya.

The main structures of Tikal cover approximately 1 square mile (2.5 square km). Surveys in a larger area, encompassing at least 6 square miles (15.5 square km), have revealed outlying smaller structures that were residences. These, however, were not arranged in streets or in close-packed formation, as in the case of Teotihuacán, but were rather widely separated. It is estimated that at its height (c. 700) the core of Tikal had a population of about 10,000 persons but that the centre drew upon an outlying population of approximately 50,000.

Tikal had no water other than what was collected from rainwater and stored in ten reservoirs. Archaeologists working in Tikal during the 20th century refurbished one of these ancient reservoirs to store water for their own use. The average annual rainfall at Tikal is 1,945 millimetres (76.6 in). However, the arrival of rain was often unpredictable, and long period of drought could occur before the crops ripen, which severely threatened the inhabitants of the city.

The site’s major structures include five pyramidal temples and three large complexes, often called acropoles; these presumably were temples and palaces for the upper class. One such complex is composed of numerous buildings beneath which have been found richly prepared burial chambers. Pyramid I is topped by the Temple of the Jaguar and rises to 148 feet (45 metres). Just west of Pyramid I and facing it is Pyramid II, standing 138 feet (42 metres) above the jungle floor and supporting the Temple of the Masks. Pyramid III is 180 feet (55 metres) high. Near the Plaza of the Seven Temples stands Pyramid V is 187 feet (57 metres). The highest of the Tikal monuments is Pyramid IV is 213 feet (65 metres), which is the westernmost of the major ruins and also the site of the Temple of the Two-Headed Serpent. Pyramid IV is one of the tallest pre-Columbian structures in the Western Hemisphere.

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, with the support of Guatemalan government, have been credited with restoring many of the remaining structures at Tikal in the 1950s and 1960s. Most of the cities buildings were made of durable limestone, and thus many have endured.

Notable structures that are still in evidence include:

- The Great Plaza, or main square of the city

- The Central Acropolis, which is believed to have served as the main palace for the city’s rulers

- The North Acropolis

- The Mundo Perdido, or “lost world” temple, a large Mayan pyramid

- The Temple of Ah Cacao or Temple of the Great Jaguar, a Mayan pyramid that served as a burial site and stretches more than 150 feet high

- Temple I, an image of which adorns the 50 centavo note in modern Guatemalan currency

The residential area of Tikal covers an estimated 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi), much of which has not yet been cleared, mapped, or excavated. The 16 square kilometres (6.2 sq mi) area around the site core has been intensively mapped; it may have enclosed an area of some 125 square kilometres (48 sq mi). A huge set of earthworks discovered by Dennis E. Puleston and Donald Callender in the 1960s rings Tikal with a 6-metre (20 ft) wide trench behind a rampart. Recently, a project exploring the defensive earthworks has shown that the scale of the earthworks is highly variable and that in many places it is inconsequential as a defensive feature. In addition, some parts of the earthwork were integrated into a canal system. The earthwork of Tikal varies significantly in coverage from what was originally proposed and it is much more complex and multifaceted than originally thought.

Archeologists are still working at Tikal and hope to map and excavate the areas that are believed to have served as the residences for the majority of the population. From the mid-1950s through the early 1970s, excavation and restoration work was overseen under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania’s Tikal Park project. Researchers working for the Tikal Project identified the remains of more than 200 structures at Tikal.

Tikal is the best understood of any of the large lowland Maya cities, with a long dynastic ruler list, the discovery of the tombs of many of the rulers on this list and the investigation of their monuments, temples and palaces. However, tourism is the primary function of Tikal National Park today, and has been for more than 50 years. The park’s main gate opens at 6 am and officially closes at 6 pm.

Information Sources: