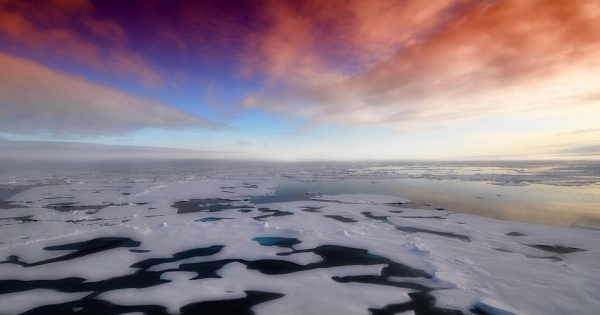

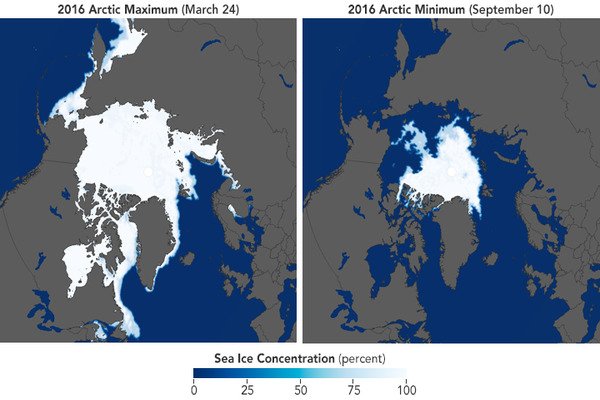

The timing of seasonal cycles isn’t the only difference between Antarctic and Arctic sea ice. The larger range between austral winter maximum extent and summer minimum extent is one significant difference. Antarctic sea ice covers approximately 7 million square miles in winter, compared to 6 million square miles in the Arctic; the Antarctic summer minimum is approximately 1 million square miles, compared to 2.5 million square miles in the Arctic.

There is currently less sea ice in the Antarctic than at any time in the forty years since satellite observation began: only 2.20 million square kilometers of the Southern Ocean were covered with sea ice in early February 2023. For the Sea Ice Portal, researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute and the University of Bremen examine the situation. Even though the melting phase in the Southern Hemisphere continues until the end of February, January 2023 had already set a new record for its monthly mean extent (3.22 million square kilometers). The current expedition team on board the RV Polarstern has just reported virtually ice-free conditions in the Bellingshausen Sea, where they are currently conducting research.

“On 8 February 2023, at 2.20 million square kilometres, the Antarctic sea ice extent had already dropped below the previous record minimum from 2022 (2.27 million square kilometres on 24 February 2022). Since the sea ice melting in the Antarctic will most likely continue in the second half of the month, we can’t say yet when the record low will be reached or how much more sea ice will melt between now and then,” says Prof Christian Haas, Head of the Sea Ice Physics Section at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), with regard to the current developments in the Antarctic.

I’ve never seen such an extreme, ice-free situation here before. The continental shelf, the size of Germany, is now completely ice-free. Though these conditions are favorable for our vessel-based fieldwork, it is troubling to consider how quickly this change has occurred.

Prof Karsten Gohl

“The rapid decline in sea ice over the past six years is quite remarkable since the ice cover hardly changed at all in the thirty-five years before. It is still unclear whether what we are seeing is the beginning of a rapid end to summer sea ice in the Antarctic, or if it is merely the beginning of a new phase characterized by low but still stable sea ice cover in the summer.”

Melting has accelerated since December 2022, particularly in the West Antarctic Bellingshausen and Amundsen Seas; the former is nearly ice-free. That is also where the research vessel Polarstern is currently exploring the evidence of past glacials and interglacials. According to expedition leader and AWI geophysicist Prof Karsten Gohl, who is now in the region for the seventh time after first visiting in 1994: “I’ve never seen such an extreme, ice-free situation here before. The continental shelf, the size of Germany, is now completely ice-free. Though these conditions are favorable for our vessel-based fieldwork, it is troubling to consider how quickly this change has occurred.”

In the course of the year, the Antarctic sea ice generally reaches its maximum extent in September or October and its minimum extent in February. In some regions, the sea ice melts completely in summer. In winter, the cold climate throughout the Antarctic promotes the rapid formation of new sea ice. At its maximum, the sea ice cover in the Antarctic is generally between 18 and 20 million square kilometers. In summer, it dwindles to roughly 3 million square kilometers, displaying far more natural annual variability than ice in the Arctic.

Further, Antarctic sea ice is much thinner than its Arctic counterpart and appears only seasonally — which explains why, for a very long time, its development was considered impossible to predict beyond a matter of days. In recent years, however, science has uncovered several mechanisms for predicting the development of sea ice on seasonal time scales. Knowing the sea ice presence weeks to months in advance is of great interest to Antarctic shipping.

Analyses of the current sea ice extent conducted by the Sea Ice Portal team show that the ice was at its lowest-ever extent recorded for the time of year since record-keeping began in 1979 for the entire month of January 2023. The monthly mean value was 3.22 million square kilometers, or about 478,000 square kilometers (roughly the size of Sweden) less than the previous low in 2017. In terms of long-term development, Antarctic sea ice is declining at a rate of 2.6 percent per decade. This is the eighth year in a row that the mean sea-ice extent in January has been lower than the long-term trend.

This intense melting could be attributed to unusually high air temperatures to the west and east of the Antarctic Peninsula, which were approximately 1.5 degrees Celsius higher than the long-term average. Furthermore, the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) is strongly positive, influencing the prevailing wind circulation in Antarctica. A low-pressure anomaly forms over Antarctica during a positive SAM phase (like today), while a high-pressure anomaly forms over the middle latitudes. This increases the strength of the westerly winds and causes them to contract toward Antarctica. As a result, upwelling of circumpolar deep water on the Antarctic continental shelf intensifies, promoting sea-ice retreat. More importantly, it accelerates the melting of ice shelves, which is critical for future global sea-level rise.

The current Polarstern expedition’s stated goal is to unravel the geological evolution of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, or the massive glaciers that cover the Antarctic continent and feed the ice shelves. It is hoped that doing so will allow us to make more accurate predictions about the ice sheet’s future development, and thus about sea-level rise in the face of constant climate change. The last interglacial, 120,000 years ago, and a prolonged warm period in the Pliocene about 3.5 million years ago, for example, are thought to be analogous to today.

Warming was solely caused by gradual changes in Earth’s orbit in both previous periods; today, these are supplemented by carbon dioxide emissions, which are produced by the use of fossil fuels and accumulate in the atmosphere. The knowledge gained from the history of the ice sheets is intended to aid in estimating how quickly and extensively they will melt when certain tipping points of today’s rapid anthropogenic climate change are exceeded. In this regard, researchers use geophysical and geological methods to investigate marine sediments at the sea floor, which contain valuable information as archives of past ice-sheet movements.

The enormous changes are also reflected in historical records. For example, during the Antarctic summer 125 years ago, the Belgian research vessel Belgica was trapped in massive pack ice for more than a year – precisely in the region where the Polarstern can now operate in completely ice-free waters. The Belgica’s crew’s photographs and diaries provide a unique chronicle of the ice conditions in the Bellingshausen Sea at the dawn of the industrial age, which climate researchers frequently use as a baseline for comparison with today’s climate change.