2.2. Development of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

In the increasingly conscience-focused marketplaces of the 21st century, the demand for more ethical business processes and actions (known as ethicism) is increasing. Simultaneously, pressure is applied on industry to improve business ethics through new public initiatives and laws (e.g. higher UK road tax for higher-emission vehicles).

Business ethics can be both a normative and a descriptive discipline. As a corporate practice and a career specialization, the field is primarily normative. In academia, descriptive approaches are also taken. The range and quantity of business ethical issues reflects the degree to which business is perceived to be at odds with non-economic social values. Historically, interest in business ethics accelerated dramatically during the 1980s and 1990s, both within major corporations and within academia. For example, today most major corporate websites lay emphasis on commitment to promoting non-economic social values under a variety of headings (e.g. ethics codes, social responsibility charters). In some cases, corporations have re-branded their core values in the light of business ethical considerations (e.g. BP’s “beyond petroleum” environmental tilt).

The term CSR itself came in to common use in the early 1970s although it was seldom abbreviated. The term stakeholder, meaning those impacted by an organization’s activities, was used to describe corporate owners beyond shareholders from around 1989.

2.3. Social Accounting, Auditing and Reporting

Taking responsibility for its impact on society means in the first instance that a company accounts for its actions. Social accounting, a concept describing the communication of social and environmental effects of a company’s economic actions to particular interest groups within society and to society at large, is thus an important element of CSR.

A number of reporting guidelines or standards have been developed to serve as frameworks for social accounting, auditing and reporting:

- Account Ability’s AA1000 standard, based on John Elkington’s triple bottom line (3BL) reporting

- Accounting for Sustainability’s Connected Reporting Framework .

- Global Reporting Initiative’s Sustainability Reporting Guidelines

- Good Corporation’s Standard developed in association with the Institute of Business Ethics

- Green Globe Certification / Standard

- Social Accountability International’s SA8000 standard

- The ISO 14000 environmental management standard

- The United Nations Global Compact promotes companies reporting in the format of a Communication on Progress (COP). A COP report describes the company’s implementation of the Compact’s ten universal principles.

- The United Nations Intergovernmental Working Group of Experts on International Standards of Accounting and Reporting (ISAR) provides voluntary technical guidance on eco-efficiency indicators, corporate responsibility reporting and corporate governance disclosure.

- Verite’s Monitoring Guidelines

The FTSE Group publishes the FTSE4Good Index, an evaluation of CSR performance of companies.

In some nations legal requirements for social accounting, auditing and reporting exist (e.g. in the French bilan social), though agreement on meaningful measurements of social and environmental performance is difficult. Many companies now produce externally audited annual reports that cover Sustainable Development and CSR issues (“Triple Bottom Line Reports”), but the reports vary widely in format, style, and evaluation methodology (even within the same industry). Critics dismiss these reports as lip service, citing examples such as Enron’s yearly “Corporate Responsibility Annual Report” and tobacco corporations’ social reports.

2.4. Potential Business Benefits

The scale and nature of the benefits of CSR for an organization can vary depending on the nature of the enterprise, and are difficult to quantify, though there is a large body of literature exhorting business to adopt measures beyond financial ones (e.g., Deming’s Fourteen Points, balanced scorecards). Orlitzky, Schmidt, and Rynesfound a correlation between social/environmental performance and financial performance. However, businesses may not be looking at short-run financial returns when developing their CSR strategy.

The definition of CSR used within an organization can vary from the strict “stakeholder impacts” definition used by many CSR advocates and will often include charitable efforts and volunteering. CSR may be based within the human resources, business development or public relations departments of an organization, or may be given a separate unit reporting to the CEO or in some cases directly to the board. Some companies may implement CSR-type values without a clearly defined team or programme. A Business farm or bank should study deeply on CSR to enhance bank value to the customers.

The business case for CSR within a company will likely rest on one or more of these arguments:

2.4.1. Human resources

My study further shows that, a CSR programme can be seen as an aid to recruitment and retention, particularly within the competitive graduate student market. Potential recruits often ask about a firm’s CSR policy during an interview, and having a comprehensive policy can give an advantage. CSR can also help to improve the perception of a company among its staff, particularly when staff can become involved through payroll giving, fundraising activities or community volunteering.

2.4.2. Risk management

Managing risk is a central part of many corporate strategies. Reputations that take decades to build up can be ruined in hours through incidents such as corruption scandals or environmental accidents. These events can also draw unwanted attention from regulators, courts, governments and media. Building a genuine culture of ‘doing the right thing’ within a corporation can offset these risks.

2.4.3. Brand differentiation

In crowded marketplaces, companies strive for a unique selling proposition which can separate them from the competition in the minds of consumers.Deep study on CSR can play a role in building customer loyalty based on distinctive ethical values. Several major brands, such as The Co-operative Group and The Body Shop are built on ethical values. Business service organizations can benefit too from building a reputation for integrity and best practice.

2.4.4. License to operate

Corporations are keen to avoid interference in their business through taxation or regulations. By taking substantive voluntary steps, they can persuade governments and the wider public that they are taking issues such as health and safety, diversity or the environment seriously, and so avoid intervention. This also applies to firms seeking to justify eye-catching profits and high levels of boardroom pay. Those operating away from their home country can make sure they stay welcome by being good corporate citizens with respect to labor standards and impacts on the environment.

2.4.5. Criticisms and concerns

Critics of CSR as well as proponents debate a number of concerns related to it. These include CSR’s relationship to the fundamental purpose and nature of business and questionable motives for engaging in CSR, including concerns about insincerity and hypocrisy.

2.5. CSR and the Nature of Business

Corporations exist to provide products and/or services that produce profits for their shareholders. Milton Friedman and others take this a step further, arguing that a corporation’s purpose is to maximize returns to its shareholders, and that since (in their view), only people can have social responsibilities, corporations are only responsible to their shareholders and not to society as a whole. Although they accept that corporations should obey the laws of the countries within which they work, they assert that corporations have no other obligation to society. Some people perceive CSR as incongruent with the very nature and purpose of business, and indeed a hindrance to free trade. Those who assert that CSR is incongruent with capitalism and are in favor of neo liberalism argue that improvements in health, longevity and/or infant mortality have been created by economic growth attributed to free enterprise.

Critics of this argument perceive neo liberalism as opposed to the well-being of society and a hindrance to human freedom. They claim that the type of capitalism practiced in many developing countries is a form of economic and cultural imperialism, noting that these countries usually have fewer labor protections, and thus their citizens are at a higher risk of exploitation by multinational corporations.

A wide variety of individuals and organizations operate in between these poles. For example, the Leadership Alliance asserts that the business of leadership (be it corporate or otherwise) is to change the world for the better. Many religious and cultural traditions hold that the economy exists to serve human beings, so all economic entities have an obligation to society (e.g., cf. Economic Justice for All). Moreover, as discussed above, many CSR proponents point out that CSR can significantly improve long-term corporate profitability because it reduces risks and inefficiencies while offering a host of potential benefits such as enhanced brand reputation and employee engagement.

2.6. CSR and Questionable Motives

Some critics believe that CSR programs are undertaken by companies such as British American Tobacco (BAT), the petroleum giant BP (well-known for its high-profile advertising campaigns on environmental aspects of its operations), and McDonald’s (see below) to distract the public from ethical questions posed by their core operations. They argue that some corporations start CSR programs for the commercial benefit they enjoy through raising their reputation with the public or with government. They suggest that corporations which exist solely to maximize profits are unable to advance the interests of society as a whole.

Another concern is when companies claim to promote CSR and be committed to Sustainable Development whilst simultaneously engaging in harmful business practices. For example, since the 1970s, the McDonald’s Corporation’s association with Ronald McDonald House has been viewed as CSR and relationship marketing. More recently, as CSR has become main stream, the company has beefed up its CSR programs related to its labor, environmental and other practices. All the same, in McDonald’s Restaurants v Morris & Steel, Lord Justices Pill, May and Keane ruled that it was fair comment to say that McDonald’s employees worldwide ‘do badly in terms of pay and conditions and true that ‘if one eats enough McDonald’s food, one’s diet may well become high in fat etc., with the very real risk of heart disease.

Similarly Shell has a much-publicized CSR policy and was a pioneer in triple bottom line reporting, however, this did not prevent the 2004 scandal concerning its misreporting of oil reserves—an act which seriously damaged its reputation and led to charges of hypocrisy. Since then, the Shell Foundation has become involved in many projects across the world, including a partnership with Marks and Spencer (UK) in three flower and fruit growing communities across Africa.

Critics concerned with corporate hypocrisy and insincerity generally suggest that better governmental and international regulation and enforcement, rather than voluntary measures, are necessary to ensure that companies behave in a socially responsible manner.

2.7. Is CSR Too much of a good thing?

Since there is so much CSR about, you might think big companies would by now be getting rather good at it. A few are, but most are struggling.

CSR is now made up of three broad layers, one on top of the other. The most basic is traditional corporate philanthropy. Companies typically allocate about 1% of pre-tax profits to worthy causes because giving something back to the community seems “the right thing to do”. But many companies now feel that arm’s-length philanthropy—simply writing cheques to charities—is no longer enough. Shareholders want to know that their money is being put to good use, and employees want to be actively involved in good works.

Money alone is not the answer when companies come under attack for their behaviour. Hence the second layer of CSR, which is a branch of risk management. Starting in the 1980s, with environmental disasters such as the explosion at the Bhopal pesticide factory and the Exxon Valdez oil spill, industry after industry has suffered blows to its reputation. Big pharma was hit by its refusal to make antiretroviral drugs available cheaply for HIV/AIDS sufferers in developing countries. In the clothing industry, companies like Nike and Gap came under attack for use of child labour. Food companies face a backlash over growing obesity. And “Don’t be evil” as a corporate motto offers no immunity: Google was one of several American technology titans hauled before Congress to be grilled about their behaviour in China.

So, often belatedly, companies respond by trying to manage the risks. They talk to NGOs and to governments, create codes of conduct and commit themselves to more transparency in their operations. Increasingly, too, they get together with their competitors in the same industry in an effort to set common rules, spread the risk and shape opinion.

All this is largely defensive, but companies like to stress that there are also opportunities to be had for those that get ahead of the game. The emphasis on opportunity is the third and trendiest layer of CSR: the idea that it can help to create value. In December 2006 the Harvard Business Review published a paper by Michael Porter and Mark Kramer on how, if approached in a strategic way, CSR could become part of a company’s competitive advantage.

That is just the sort of thing chief executives like to hear. “Doing well by doing good” has become a fashionable mantra. Businesses have eagerly adopted the jargon of “embedding” CSR in the core of their operations, making it “part of the corporate DNA” so that it influences decisions across the company.

With a few interesting exceptions, the rhetoric falls well short of the reality. “It doesn’t go very deep yet,” says Bradley Googins, executive director of the Boston College Centre for Corporate Citizenship. His centre’s latest survey on the state of play in America is called “Time to Get Real”.

There is, to be fair, study shows some evidence that companies’ efforts are moving in a more strategic direction. The Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy, a New York-based business association, reports that the share of corporate giving with a “strategic” motivation jumped from 38% in 2004 to 48% in 2006. But too often corporate strategy is not properly joined up. In the car industry, Toyota has led the way in championing green, responsible motoring with its Prius hybrid model, but it has lobbied with others in the industry against a tough fuel-economy standard in America. Surveys point to a big gap between companies’ aspirations and their actions (see chart 2). And even corporate aspirations in the rich world lag far behind how much the public expects business to contribute to society.

According to Mr Porter, despite a surge of interest in CSR, in most cases it remains “too unfocused, too shotgun, too many supporting someone’s pet project with no real connection to the business”. Dutch Leonard, like Mr Porter at HarvardBusinessSchool, describes the value-building type of CSR as “an act of faith, almost a fantasy. There are very few examples.”

Perhaps that is not surprising. The business of trying to be good is confronting executives with difficult questions. Can you measure CSR performance? Should you be co-operating with NGOs, and with your competitors? Is there really competitive advantage to be had from a green strategy? How will the rise of companies from China, India and other emerging markets change the game?

Based on my study this special report will look in detail at how companies are implementing CSR. It will conclude that, done badly, it is often just a fig leaf and can be positively harmful. Done well, though, it is not some separate activity that companies do on the side, a corner of corporate life reserved for virtue: it is just good business.

2.8. CSR Expenditures by Banks

The banking sector of Bangladesh has a long history of involvement in benevolent activities like donations to different charitable organizations, to poor people and religious institutions, city beautification and patronizing art & culture, etc. Recent trends of these engagement indicates that banks are gradually organizing these involvements in more structured CSR initiative format, in line with BB Guidance in DOS circular no. 01 of 2009.

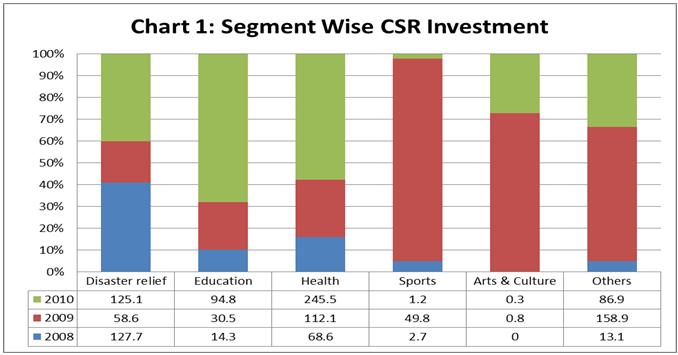

The June 2009 BB Guidance circular suggested that banks could begin reporting their CSR initiatives in a modest way as supplements to usual annual financial reports, eventually to develop into full blown comprehensive reports in GRI format. Information on CSR expenditure available from annual reports of banks, compiled together, bring up the following picture of sectorial patterns:

Table-2.1: Sectorial pattern of CSR expenditure reported by banks

(Taka in million)

| Segments | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

| Disaster relief | 127.7 | 58.6 | 125.1 |

| Education | 14.3 | 30.5 | 94.8 |

| Health | 68.6 | 112.1 | 245.5 |

| Sports | 02.7 | 49.8 | 1.2 |

| Arts & Culture | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Others | 13.1 | 158.9 | 86.9 |

| Total | 226.4 | 410.7 | 553.8 |

In the year 2008, large concentration in the field of disaster relief, both in participation and expenditure wise, was observed mainly because of the cyclone ‘Sidr’. Whereas, in the year 2009 & 2010, the ‘Education’ and ‘Health’ sectors were getting more attention and appeared to be the most popular area for CSR activities as huge investments are being made by several banks in these segments. These shifts point to the responsiveness of the banking community to the changing need of the society.

Following are some notable features observed from the CSR activities carried out by the banks:

- In a natural calamity-prone area like Bangladesh, there remains an existing and distinctive CSR agenda focused on the business contribution to tackling social crises in the affected area. Disaster relief and rehabilitation became the segment where the highest number of banks participated to help ease the sufferings of the affected people. In the

- current context, a desired move from the traditionally popular fields of education or health.

- In the education segment, more and more banks have taken long-term or renewable scholarship programs for under-privileged but meritorious students for the persuasion of their studies instead of providing one time recognition awards to good performers.

- Some banks choose to provide continued financial support for maintaining operating costs of health care organizations. A bank undertook a continuous program called ‘Smile Brighter Program’ to perform as many operations possible per year on cleft-lipped boys and girls to bring back smile on their face.

- Several banks have taken steps and introduced investment schemes to cater the needs of

Self employment and poverty alleviation under which micro-finance is channeled to the

- Target groups, such as poor farmers, landless peasants, women entrepreneurs, rootless

slum people, handicapped people, etc.

- A few banks have taken steps to introduce Interest-free Education Loan to poor and meritorious students to help bear monthly educational expenditure including food, accommodation etc. The loan is distributed to the selected students in monthly installments till their completion of studies up to the Masters Degree level.

- A good number of banks have created separate Foundation/Trusts as non-profitable, nongovernmental organization, solely devoted to the cause of charity, social welfare and other benevolent activities towards the promotion CSR objectives. These banks are providing a certain percentage of the pre-tax pro_it/net pro_it each year towards its CSR activities.

2.9. Institutionalizing CSR at Corporate Level

The BB guidance circular suggested embracing of CSR with decisions taken at the highest corporate level (board of directors of the bank), and to choose action programs and performance targets through a consultative processes involving the internal and external stakeholders concerned. As seen in the following table, 12 PCBs and 3 FCBs reported to have embraced CSR with decision at the highest corporate level, none of the SCBs and DFIs reported to have done anything in this regard. A total of 16 out of 30 PCBs and 1 out of 9 FCBs have formed separate Foundations or Trusts as non-profitable, non-governmental organization, solely devoted to the cause of charity, social welfare and other benevolent activities towards the promotion CSR objectives. These banks have also resolved to provide a certain percentage of the pre-tax profit/net profit each year towards its CSR activities. However, none of the banks reported to have adopted action programs and performance targets through consultative processes involving the internal and external stakeholders concerned as suggested in the guideline of June 1, 2008.

Compliance issue | SCBs (Nns. 4) | DFIs (Nos. 5) | PCBs (Nos. 30) | FCBs (Nos. 9) |

| Embraced CSR with decision at the highest corporate level | 0 | 0 | 12 | 3 |

| Set up separate body/division/unit in order to mainstreaming CSR activities | 0 | 0 | 16 | 1 |

| Adopted action programs & targets through consultative process involving internal and external stakeholders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table-2.2: Institutionalizing CSR at corporate level

2.9.1. Ingraining CSR practices within the organization & client businesses

Against the suggestion in the BB guidance circular for ingraining environmentally and socially responsible practices within the organization, only four banks (1 DFI and 3 PCBs) reported having taken steps for adoption of socially and environmentally responsible practices in their own internal operations. The DFI mentioned that they have taken actions towards providing a modern, healthy and safe workplace and creating an environment conducive to learning and development. Regarding reducing the environmental impact as a result of their operation and business activity 1 DFI and 3 PCBs reported to have taken positive actions towards it.

Compliance issue | SCBs (Nns. 4) | DFIs (Nos. 5) | PCBs (Nos. 30) | FCBs (Nos. 9) |

| Adopted socially and environmentally responsible practices in own internal operations | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Providing a modern, healthy and safe workplace and creating a learning and development environment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Reduce the bank’s environmental impact as a result of its operation and business activity | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Foster CSR in their client businesses assessing the social and environmental impacts of the projects seeking finance | 1 | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Ensuring compliance of regulatory environmental and social requirements | 1 | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Engaging with clients in assessing project’s social and environmental impacts beyond the regulatory requirements | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Table-2.3: Ingraining CSR practices in the banks and their client businesses

As shown in the above table, 1 SCB, 2 DFIs and 8 PCBs have taken steps to foster CSR in their

client businesses in various economic sectors, assessing the social and environmental impacts of the enterprises/projects seeking finance. These banks reported that they try to ensure compliance with environmental standards while financing industrial projects, and that they have formulated environment policies in accordance with guidelines issued by the Government, in terms of which the environmental impacts are considered at the time of conducting Credit and Lending Risks Analysis. Projects likely to have adverse impact on environment are strongly discouraged by them. Some banks have also introduced guidelines requiring assessment of environmental and social impacts of the projects to ensure that operations of the projects would be eco-friendly. It is understood that, banks in Bangladesh in general try to ensure that enterprises projects seeking finance comply with the environmental and social requirements that are compulsorily mandated by laws and regulations. However, most of the banks did not report this in their annual reports.

For more parts of this post-

An Empirical Study On Southeast Bank Limited.(Part-1)

An Empirical Study On Southeast Bank Limited.(Part-2)

An Empirical Study On Southeast Bank Limited.(Part-3)

An Empirical Study On Southeast Bank Limited.(Part-4)

An Empirical Study On Southeast Bank Limited.(Part-5)