Recent research has discovered a new biomarker that indicates chronic stress resilience. This biomarker is generally absent in persons with severe depressive illness, and its absence is linked to pessimism in daily life, according to the study. Emory University researchers reported their findings in Nature Communications.

The researchers utilized brain imaging to look for variations in glutamate levels in the medial prefrontal cortex before and after study participants completed stressful activities. They then tracked the individuals for four weeks, using a survey methodology to determine how they rated their expected and experienced results for everyday activities on a regular basis.

“To our knowledge, this is the first work to show that glutamate in the human medial prefrontal cortex shows an adaptive habituation to a new stressful experience if someone has recently experienced a lot of stress,” says Michael Treadway, senior author of the study and professor in Emory’s Department of Psychology and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science.

“Importantly, this habituation is significantly altered in patients with depression. We believe this may be one of the first biological signals of its kind to be identified in relation to stress and people who are clinically depressed.”

The pandemic has created more isolation for many people, while also increasing the amount of severe stressors and existential threats they experience.

Michael Treadway

“Learning more about how acute stress and chronic stress affect the brain may help in the identification of treatment targets for depression,” adds Jessica Cooper, first author of the study and a post-doctoral fellow in Treadway’s Translational Research in Affective Disorders Laboratory.

The lab’s research focuses on the molecular and circuit-level underpinnings underlying psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and decision-making. Stress has long been recognized as a significant risk factor for depression, one of the most frequent and devastating mental diseases.

“In many ways, depression is a stress-linked disorder,” Treadway says. “It’s estimated that 80 percent of first-time depressive episodes are preceded by significant, chronic life stress.”

Approximately 16 to 20% of the population in the United States will have a serious depressive illness at some point in their lives. Experts believe that as the COVID-19 epidemic continues, depression rates will rise even more.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, roughly four out of ten persons in the United States have experienced symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder during the pandemic, up from one out of ten in 2019.

“The pandemic has created more isolation for many people, while also increasing the amount of severe stressors and existential threats they experience,” Treadway says. “That combination puts a lot of people at high risk for becoming depressed.”

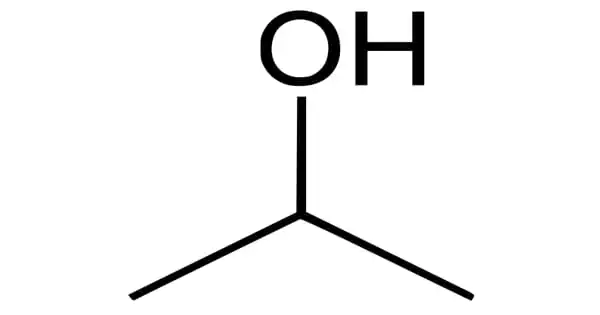

Although the link between stress and depression is well understood, the processes that underpin it are not. Stress and the reaction of glutamate, the principal excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain, have been linked in rat studies. However, the significance of glutamate in depression in humans is less apparent.

People without a mental health condition and unmedicated individuals diagnosed with a severe depressive illness were among the 88 participants in the current investigation. Before undergoing trials employing a brain scanning technology known as magnetic resonance spectroscopy, participants were asked about recent stress in their lives.

Participants were instructed to alternate between executing two activities that acted as acute stressors while in the scanner: dipping their hand up to the wrist in ice water and counting down from 2,043 by 17 steps while someone evaluated their accuracy.

Glutamate levels in the medial prefrontal cortex, which is involved in thinking about one’s situation and developing expectations, were examined in brain scans before and after the acute stressor. This brain region has also been linked to the regulation of adaptive stress responses, according to a previous study.

The researchers were able to demonstrate that the tasks induced a stress response by measuring the level of the stress hormone cortisol in the saliva samples supplied by the participants while in the scanner.

Individual levels of recent perceived stress predicted glutamate change in response to stress in the medial prefrontal cortex in healthy people, according to brain scans. Healthy people with lower stress levels produced more glutamate in reaction to acute stress, whereas healthy people with greater stress levels produced less glutamate in response to acute stress. In individuals diagnosed with depression, this adaptive response was noticeably lacking.

“The decrease in the glutamate response over time appears to be a signal, or a marker, of a healthy adaptation to stress,” Treadway says. “And if the levels remain high that appears to be a signal for maladaptive responses to stress.”

The original finding for adaptation in healthy people was promising, but the sample size was small, so the researchers tried to duplicate it. “Not only did we get a replication, it was an unusually strong replication,” Treadway says.

A set of healthy controls was also included in the study, who were scanned before and after doing activities. Instead of demanding tasks, the controls were instructed to immerse their hand in warm water or count out loud consecutively. They did not have a salivary cortisol response and their glutamate levels were not linked to subjective stress.

The researchers tracked individuals for four weeks following scanning to supplement their results. The participants reported on their expected and actual outcomes for activities in their everyday lives every other day. The findings revealed that glutamate alterations that were higher than expected based on a person’s degree of perceived stress suggested a more gloomy perspective, which is a sign of depression.

“We were able to show how a neural response to stress is meaningfully related to what people experience in their daily lives,” Cooper says. “We now have a large, rich data set that gives us a tangible lead to build upon as we further investigate how stress contributes to depression.”

The work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health.