Creating an adaptive, effective multi-arm Phase 2 clinical trial for glioblastoma necessitates careful consideration of a number of criteria, including patient population, treatment arms, statistical methodologies, and ethical considerations.

The first results of an innovative phase 2 clinical trial led by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in partnership with ten major brain tumor centers throughout the country to uncover new possible treatments for glioblastoma have been published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. While none of the three medicines tested thus far have improved patients’ overall survival, this adaptive platform study, the first of its type in neuro-oncology, offers the potential to quickly and efficiently uncover therapies that help patients.

The trial, called INSIGhT, is still underway testing additional therapies.

“There have been many failed attempts to find better therapies for glioblastoma,” says co-first author and Dana-Farber radiation oncologist Rifaquat Rahman, MD. “This new trial design meets a need for a more efficient and smarter way to find new therapies.”

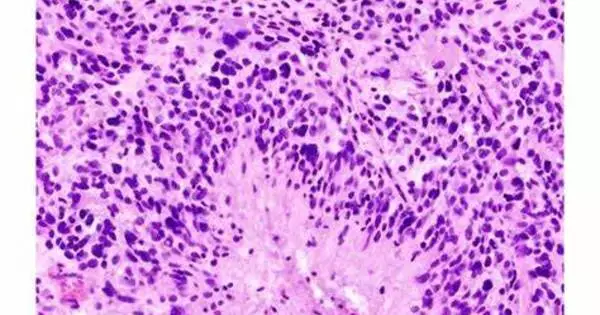

Glioblastoma, the most prevalent type of primary brain tumor, has few viable therapeutic options. Those suffering from MGMT unmethylated glioblastoma fare the worst and seldom respond to traditional therapy of radiation and chemotherapy.

This is a dynamic, evolving trial that will continue to test new therapies that could potentially benefit patients. This trial is more streamlined, but it’s also rigorous, which makes it more likely that it will produce more reliable answers about whether or not a drug is worth further investment.

Rifaquat Rahman

Traditionally, investigational therapies for glioblastoma are tested either head-to-head against standard therapy, or on their own in a single-arm trial with no control arm. In contrast, INSIGhT (Individualized Screening Trial of Innovative Glioblastoma Therapy) uses a shared control arm to test multiple investigational therapies at one time. So far, INSIGhT has tested a control arm of standard therapy against abemaciclib (a CDK4/6 inhibitor), neratinib (an EGFR/HER2 inhibitor), and CC-115 (a DNA-PK/mTOR inhibitor).

“This design is more economical and faster than the alternative of three separate randomized phase 2 trials, which would require many more patients and a lot more resources,” explains co-senior author and principal investigator Patrick Wen, MD, Director of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s Center for Neuro-Oncology.

The experiment enrolled 237 individuals with newly diagnosed MGMT unmethylated glioblastoma between 2017 and 2021 in this first analysis of data. Patients were first randomized to one of four treatments at random. Each patient had a 25% chance of receiving any of the four possibilities.

Once underway, the trial adapts to new information. Dana-Farber statisticians led by Lorenzo Trippa, Ph.D., continuously apply complex statistics to learn from each patient whether the drug they are receiving is a likely benefit. The randomization algorithms enable future patients joining the trial to have increased odds of getting the best drug for them personally.

For example, if patients had side effects or showed no indicators of benefit from a treatment choice, future patients would be less likely to receive that treatment. If another treatment option proved to be more beneficial to patients, future patients would be more likely to be assigned to it. The system also considers biomarkers linked to the likelihood of benefit from a certain therapy.

This method, known as Bayesian Adaptive Randomization, decreases the number of patients who are exposed to medications that are unlikely to be effective. It also assists researchers in allocating funding to medicines that show the most potential. “We can quickly stop pursuing drugs that are not promising and at the same time find the effective drugs and move them into phase three testing,” Wen states.

Simultaneously, the trial has established an infrastructure that will assist researchers in learning more about why patients respond or do not respond to the medicines. This is one of the first neuro-oncology trials to involve tumor genomic sequencing for all patients at the outset, which allows researchers to learn more about how genetic biomarkers influence responses.

“It’s a very modern, science-enabling trial,” says co-senior author Keith Ligon, MD, PhD, a Dana-Farber pathologist and Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Chief of the Division of Neuropathology. Patients receiving abemaciclib plus neratinib had longer progression-free survival than those getting conventional therapy or CC-115 in this first readout of the trial. None of the treatments improved overall survival.

The trial will include new treatment arms. It is currently randomly allocating new patients to either a novel brain penetrant chemotherapy regimen (QBS10070S), an immunotherapy treatment comprised of a tumor vaccine VBI-1901 and a PD1 antibody, or standard therapy.

“This is a dynamic, evolving trial that will continue to test new therapies that could potentially benefit patients,” Rahman states. Because this trial is already established, testing a medicine that has the potential to assist patients with glioblastoma may be easy. Each new trial arm is an addition to the trial, not a new trial in and of itself.

“This trial is more streamlined, but it’s also rigorous, which makes it more likely that it will produce more reliable answers about whether or not a drug is worth further investment,” says Rahman.