The Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labor in Supply Chains Act was just passed by the Canadian government. By mandating businesses to declare their efforts to eliminate labor abuse from their supply networks, the new rule is intended to combat forced labor and child labor in supply chains.

The law, also referred to as Canada’s Modern Slavery Act, does not mandate that major Canadian corporations take concrete steps to prevent or lower the likelihood of forced labor and child labor in their supply chains.

The act also doesn’t hold companies accountable when forced labor is found. Similar weak disclosure laws in California, the United Kingdom and Australia have already been found to be ineffective by academic researchers.

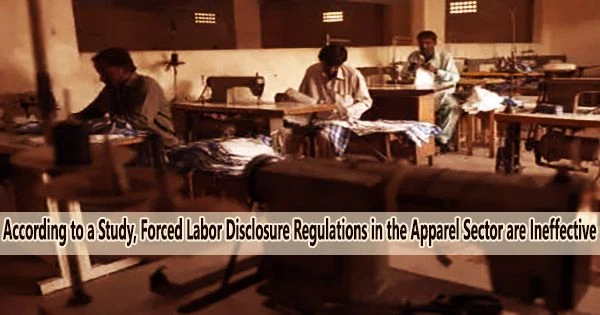

Our recent investigation at the Governing Forced Labour in Supply Chains Project into the Canadian apparel company Lululemon Athletica casts doubt on the ability of this new law to tackle labor abuse.

The new regulation falls short of what is needed to force big businesses to take the necessary precautions to prevent labor abuse in their supply chains.

Remembering Rana Plaza

This new Canadian law comes a decade after the tragic collapse of the nine-story Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh that killed nearly 1,130 garment workers and injured over 2,500. Concerns regarding the capacity of voluntary business actions to resolve labor rights breaches and protect workers were raised in the wake of the catastrophe.

The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh was developed in reaction to the catastrophe by businesses, retailers, and labor unions. The agreement was created to increase worker security and avert future accidents in the apparel industry.

Building on this initiative, the International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry with 198 brand and retailer signatories was introduced in 2021.

Remarkably, only one Canadian garment company Loblaw Companies Ltd., the parent company of the Joe Fresh brand has signed the accord. Other Canadian companies prefer their own voluntary initiatives.

These feeble corporate initiatives may be addressed by legislation intended to address forced labor in supply chains, but only if the law is robust enough.

Lululemon report

Our report, “Lululemon’s Conundrum: Good Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives and the Persistence of Forced Labour,” examines Lululemon’s efforts to address potential labor abuse in its supply chain.

In 2021, KnowTheChain, which evaluates companies’ efforts to address forced labor risks in their supply chains based on international labor standards, ranked Lululemon first among 129 apparel and footwear companies for its measures to address forced labor risks.

Lululemon was found to be at a high risk of sourcing from the Xinjiang region in China, which has been linked to forced labor and human rights abuses, despite being a leader in the industry in this regard, according to a Sheffield Hallam University investigation that same year.

Lululemon responded to this allegation by stating that it had zero tolerance for forced labor, was committed to all the workers in its worldwide supply chain, and routinely conducted due diligence on vendors around the world.

Lululemon supplier concerns

Lululemon does not own or operate any of the manufacturing or raw materials facilities used to make its apparel. Its April 2023 supplier list revealed the company sourced from suppliers located in four out of the 10 worst countries for workers’ rights violations according to the 2021 Global Rights Index created by International Trade Union Confederation: Bangladesh, Colombia, the Philippines and Turkey.

According to the supplier list, one of Lululemon’s largest manufacturing facilities is in Bangladesh, with over 13,000 workers 70 percent of whom are women. Despite this, Lululemon has not signed the 2021 International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry.

Two reports found that from 2018 to 2019, workers at a Lululemon supplier factory had to work two to three nights without being allowed to go home or take necessary breaks.

While a 2022 follow-up investigation determined Lululemon and the supplier had rectified this situation, some workers reported they still felt unable to refuse overtime requests.

In the follow-up study, it was revealed that the supplier at the same facility had also employed severe measures to prevent workers from organizing, including as sacking the union’s elected officers and allegedly threatening to liquidate the business.

While many of the anti-union issues had been resolved, the follow-up study discovered that some managers had apparently made remarks that might have been interpreted as still discouraging employees from joining the union.

Corporate transparency issues

Lululemon has several codes and policies in place to address forced labor. One is the Lululemon Global Code of Business Conduct and Ethics, which mandates that, unless the code establishes a higher norm, employees and vendors must abide by the labor and employment laws of the nations in which they conduct business.

Any infractions of this code should be reported by employees either internally through Lululemon or externally utilizing third-party resources like the global Integrity Line. This phone line allows employees to anonymously report complaints at any time.

Third-party complaint channels, however, present difficulties, such as demanding tech access, putting one’s trust in unknowledgeable strangers, and submitting a complaint that protects one’s privacy while still offering sufficient detail regarding employee issues.

Another code Lululemon has in place is the Vendor Code of Ethics and its accompanying Benchmarks policy.

Vendors are in charge of executing the code of ethics’ important provisions, including developing grievance and disciplinary procedures for transgressions and instructing staff members on its contents. Vendors are in charge of making sure subcontractors follow the policy when they employ subcontractors.

While Lululemon can conduct unannounced visits to monitor their compliance with the Vendor Code of Ethics, this is rarely done. Only one percent of assessments in 2019 were unannounced.

Additionally, Lululemon occasionally engages the services of third-party auditors, which can be problematic because these auditors rely on their customers to stay in business, casting doubt on the veracity of auditing reports.

Reliance on local labor laws

Lululemon’s measures to address forced labor largely rely on the labor laws in the countries in which the suppliers are located. Relying on local labor laws is a major shortcoming of many corporate initiatives, since they often fall short of international legal norms and are not well enforced.

In California, the United Kingdom and Australia, Lululemon is required by law to report on its efforts to detect, remedy and eradicate forced labor in its supply chains. However, the information necessary for evaluating the effectiveness of these initiatives is not available to researchers, the public or workers.

The length of lead time suppliers are given for orders and whether or not suppliers are paid on time are crucial details regarding all the players and purchasing procedures in a supply chain that are not provided. Additionally, information on how workers navigate Lululemon’s policies and grievance mechanisms is not publicly available.

Due diligence legislation needed

Our study raises concerns about the effectiveness of current transparency and disclosure laws as an effective tool for combating forced labor in supply chains.

Disclosure laws, like those in Canada’s new act, will not require Lululemon to reveal the type of information needed to ensure its suppliers are not abusing workers. Nor does the new law require large multinational corporations to take any steps to eradicate labor abuses in the supply chains.

Our study suggests disclosure laws are a form of window dressing that can be used by companies to project an image of social responsibility to consumers, rather than genuinely improving the working conditions for supply chain workers.

It’s time to require companies to take real steps to rid their supply chains of labor abuse. Before another catastrophe like Rana Plaza happens, Canada requires required due diligence legislation that incorporates supply chain workers at every stage of the process in order to completely remove forced labor in global supply networks.