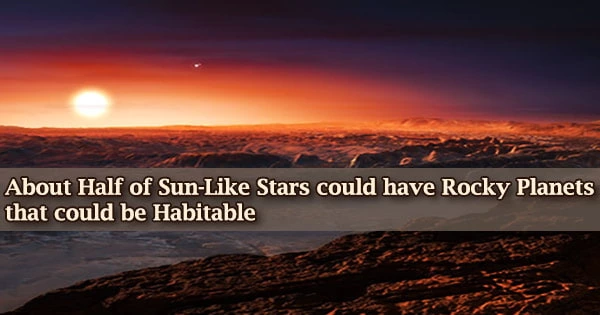

Since astronomers established the existence of exoplanets or planets outside our solar system, humanity has questioned how many of them may support life. We’re one step closer to finding a solution now.

According to recent research based on data from NASA’s decommissioned planet-hunting mission, the Kepler space telescope, nearly half of the stars with temperatures equal to our Sun could have a rocky planet with liquid water on its surface.

Based on even the most conservative interpretation of the findings in a new study to be published in The Astronomical Journal, our galaxy has at least 300 million of these potentially livable worlds.

Some of these exoplanets could even be our interstellar neighbors, as at least four are within 30 light-years of our Sun, with the nearest being at most 20 light-years away.

These are the bare minimums of such planets, based on the most cautious estimate that such worlds exist in 7% of Sun-like stars. There could be many more if the average projected rate of 50% is met.

This research aids us in determining whether or not these planets contain the necessary components to support life. This is an important aspect of astrobiology, which studies the origins and future of life in our cosmos.

The research was written by NASA scientists who worked on the Kepler project with international collaborators. The space telescope was deactivated by NASA in 2018 when it ran out of fuel. The studies of the telescope over the course of nine years revealed that our galaxy has billions of planets, far more than stars.

“Kepler already told us there were billions of planets, but now we know a good chunk of those planets might be rocky and habitable,” said the lead author Steve Bryson, a researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley.

“Though this result is far from a final value, and water on a planet’s surface is only one of many factors to support life, it’s extremely exciting that we calculated these worlds are this common with such high confidence and precision.”

Knowing how common different kinds of planets are is extremely valuable for the design of upcoming exoplanet-finding missions. Surveys aimed at small, potentially habitable planets around Sun-like stars will depend on results like these to maximize their chance of success.

Michelle Kunimoto

The scientists looked at exoplanets with a radius between 0.5 and 1.5 times that of Earth to calculate this occurrence rate, focusing on planets that are most likely rocky. They also looked for stars that were similar to our Sun in age and temperature, with temperatures ranging from minus 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit to plus 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

That’s a lot of different stars, each with its unique set of characteristics that influence whether the rocky planets in its orbit can support liquid water. These intricacies are one of the reasons why calculating the number of potentially habitable planets is so challenging, especially when even our most powerful telescopes can only detect these small worlds. As a result, the study team took a different method.

Rethinking How to Identify Habitability

This new discovery advances Kepler’s initial objective of determining the number of potentially habitable worlds in our galaxy. Previous estimates of the frequency, commonly known as the occurrence rate, of such planets, neglected the relationship between the temperature of the star and the types of light it emits and absorbs.

The new approach takes these interactions into consideration, giving researchers a better idea of whether a planet is capable of maintaining liquid water and, potentially, life.

Combining Kepler’s final collection of planetary signals with data on each star’s energy output from a huge treasure of data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission allows for this strategy.

“We always knew defining habitability simply in terms of a planet’s physical distance from a star, so that it’s not too hot or cold, left us making a lot of assumptions,” said Ravi Kopparapu, an author on the paper and a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Gaia’s data on stars allowed us to look at these planets and their stars in an entirely new way.”

Based on a star’s flux, or the total amount of energy emitted in a given area over a given time, Gaia calculated the amount of energy that falls on a planet from its host star. This allowed the researchers to conduct their research in a way that recognized the diversity of our galaxy’s stars and solar systems.

“Not every star is alike,” said Kopparapu. “And neither is every planet.”

Though the specific effect is still being studied, a planet’s atmosphere influences the amount of light required to allow liquid water to form on its surface.

Using a conservative estimate of the atmosphere’s effect, the researchers calculated a probability of rocky planets capable of supporting liquid water on their surfaces of roughly 50% of Sun-like stars. A more optimistic definition of the habitable zone puts the figure at around 75%.

Kepler’s Legacy Charts Future Research

This finding builds on a lengthy history of examining Kepler data to determine an occurrence rate, and it paves the way for future exoplanet investigations based on how prevalent these rocky, potentially habitable worlds are now expected to be.

Future research will refine the rate, informing the possibility of discovering these types of planets and guiding plans for the next stages of exoplanet research, including future observatories.

“Knowing how common different kinds of planets are is extremely valuable for the design of upcoming exoplanet-finding missions,” said co-author Michelle Kunimoto, who worked on this paper after finishing her doctorate on exoplanet occurrence rates at the University of British Columbia, and recently joined the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Surveys aimed at small, potentially habitable planets around Sun-like stars will depend on results like these to maximize their chance of success.”

The data collected by the Kepler satellite observatory continues to produce vital new findings about our location in the cosmos after revealing more than 2,800 verified planets outside our solar system.

Despite the fact that Kepler’s field of vision was only 0.25 percent of the sky, or the area that your hand would cover if held up at arm’s length to the sky, scientists have been able to extrapolate what the mission’s data means for the remainder of the galaxy. TESS, NASA’s current planet-hunting telescope, is continuing this effort.

“To me, this result is an example of how much we’ve been able to discover just with that small glimpse beyond our solar system,” said Bryson. “What we see is that our galaxy is a fascinating one, with fascinating worlds, and some that may not be too different from our own.”