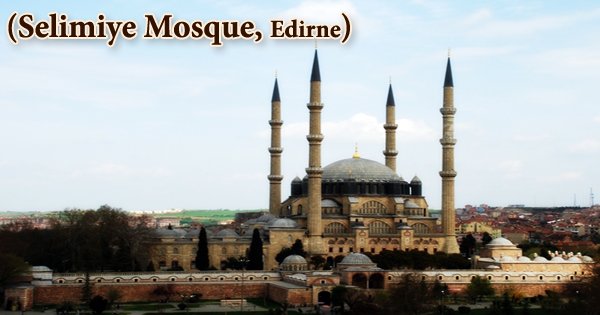

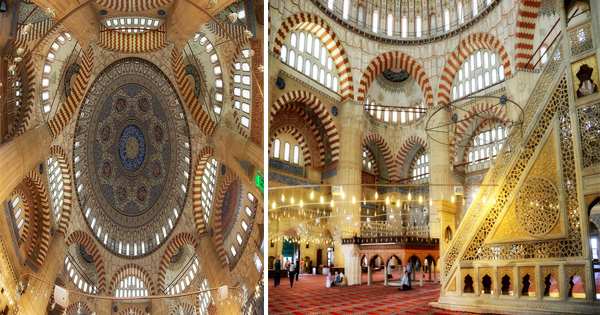

The Selimiye Mosque (Turkish: Selimiye Camii) is an Ottoman imperial mosque in Edirne, Turkey, and it was designed by Ottoman architect Mimar Koca Sinan (1497–1588), whose best-known works adorn Istanbul’s skyline. This exquisite World Heritage-listed mosque is Edirne’s most cherished building; the mosque is located in the city of Edirne (formerly Adrianople), Turkey. Sultan Selim II commissioned the mosque, which was designed between 1568 and 1575 by the imperial architect Mimar Sinan. The mosque, which has four 71-meter-high minarets, was built in the center of a large külliye (mosque complex) that included a medrese (Islamic higher education), darül Hadis (Hadith school), and arasta (arcade of shops). The mosque, along with the two madrasas on its southeast and southwest sides, is set in a 190 m × 130 m courtyard. Sinan considered the mosque to be his masterpiece, and it is one of the finest examples of Islamic and Ottoman architecture. In 2011, it was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The magnificent Selimiye Mosque and its “külliye” (social complex) were completed in just seven years after the foundation stone was laid in 1568. Around 15,000 artisans are thought to have come to the city to work on the complex and mosque. The final result was a work that represented the pinnacle of Sinan’s career as well as the pinnacle of Ottoman art and architecture in the form of a mosque. Sinan used an octagonal supporting structure in this mosque, which is made up of eight pillars incised in a square shell of walls. The four semi-domes at the square’s corners, behind the arches that spring from the pillars, serve as a transition between the massive encompassing dome (31.25 meters (102.5 feet) diameter with spherical profile) and the walls. The main entrance is located in the western courtyard, which is home to a beautiful marble şadırvan (ablution fountain). Within, a remarkably spacious interior is created by eight unobtrusive pillars, arches, and external buttresses that support the broad, lofty dome at 31.3m, slightly wider than Istanbul’s Aya Sofya. The dome’s walls are strong enough to support hundreds of windows, which allow light to shine through and highlight the interior’s colorful calligraphic decorations. While traditional mosques had a segmented interior, Sinan’s design in Edirne featured a framework that enabled visitors to see the mihrab from any point inside the mosque. The Mosque of Selim II has a grand dome atop it, surrounded by four tall minarets. Many additions surrounded the mosque, including libraries, classrooms, hospices, baths, poor-soup kitchens, markets, hospitals, and a cemetery.

The mosque has a rectangular, nearly square prayer hall and a courtyard with porticoes on the north side. The courtyard has three entrances: north, east, and west. A 12-sided fountain stands in the courtyard’s middle. The portico for latecomers has paneled vaults in two bays and domes in the remaining bays. Each corner of the prayer hall has a nearly 71-meter-high minaret with three balconies. Three separate staircases lead to the balconies of the minarets on the northeast and northwest corners. The Selimiye Mosque complex continues to dominate Edirne’s skyline today, with four slender minarets visible from all corners of the city. A higher education institution, a covered market, a clock house, an outer courtyard, and a library are all located within the compound. The roof of the prayer hall is the key feature that distinguishes the Selimiye Mosque as a significant architectural work. The massive dome, which measures 31.28 meters in diameter, is supported by eight 12-sided pillars. The dome reaches a height of 42.25 meters. The transition zone is characterized by massive squinches. The east and west pillars are each protected by two buttresses, which are hidden by the porticoes and galleries on the outside. Within, galleries adorn the gaps between the walls and the pillars. The mihrab is pulled back into an apse-like alcove with enough depth for three-sided window illumination. This makes the tile panels on the lower walls of the building sparkle with natural light. The main hall and the dome-covered square combine to create a fused octagon. Despite its wide dome, thanks to Sinan’s architectural creativity, the mosque’s main hall has no dividers, allowing it to accommodate 6,000 Muslims for prayer. Sinan built the complex in a way that stressed both material and spiritual unity, rumored to have drawn inspiration from the architectural details of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia. The half domes, weight towers, and buttresses crowded around the great dome had harmoniously interacted with it as it rose subtly from the top. The circular architecture was thought to affirm humanity’s oneness and to draw attention to the basic philosophy of the circle of life. Through the simple and strong framework of the dome and the bare stone, the visible and unseen symmetries that were called out from the exterior and interior of the mosque were meant to invoke God’s perfection. The building’s main exterior walls are made of ashlar, while the main portal, mihrab, and minbar are made of marble. Underglaze-painted Iznik tiles adorn the walls of the domed room for the mihrab, the sultan’s loge, the tympana of the windows, and the spandrels of the women’s gallery. Geometrical and floral designs, calligraphy, and carved and mother-of-pearl inlaid wood fixtures adorn the mosque’s painted adornments. Masterpieces include the carved marble mihrab, a semicircular niche that shows the path of the Kaaba in Mecca, which Muslims should face during prayer, and the minbar (pulpit). The mosque’s interior attracted a lot of attention for its clean, simple lines in structure. Lights poured in through a plethora of tiny screens, and the interplay of poor light and shadow was perceived as humanity’s insignificance. During the Ottoman-Russian war of AH 1293 / AD 1877–8, a part of the sultan’s loge’s tiles was torn down and transported to Moscow. There are still traces of the damage caused by Bulgarian artillery during the Balkan Wars in 1913. The Selimiye Mosque was restored between 1954 and 1971 and is still used as a place of worship today. The mosque and its enclosed bazaar have kept their original appearance and are still in use today. Following the establishment of modern Turkey, the schools were converted into a museum dedicated to Sinan and the mosque itself.