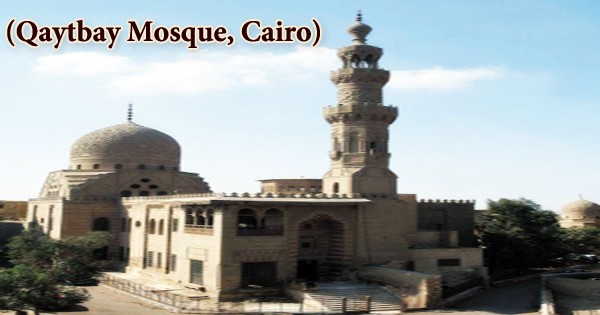

The funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay (Qaitbay, Qaitbey, Qaytbey) is an Islamic complex in Cairo, Egypt, consisting of a kuttab, mosque, and madrasa. It is a 1474 architectural complex in Cairo’s Northern Cemetery created by Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay. It is represented on the Egyptian one-pound note and is widely regarded as one of the most magnificent and accomplished monuments of late Egyptian Mamluk architecture. In 1979, the complex was designated as part of Historic Cairo as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sultan Qaytbay, like al-Nasir Muhammad in the fourteenth century, was a prolific builder of different institutions in Egypt throughout his reign. Throughout reality, he is credited with the construction of 85 structures in Syria, Palestine, Mecca, Alexandria, and Cairo. His rule was long enough for distinct styles to emerge in the numerous notable monuments he commissioned. Sultan al-Ashraf Barsbay (ruled 1422–1438) bought Al-Ashraf Qaytbay, a Mamluk, and he served under several Mamluk sultans, the last of whom, Sultan al-Zahir Timurbugha (ruled 1467-1468), designated him amir al-kabir, the highest post for an amir under the sultan. Nonetheless, he is remembered as a successful king who provided long-term peace to Egypt while in power, and as one of the biggest patrons of architecture during the Mamluk period, particularly during the Burji Mamluk period, which was otherwise distinguished by Egypt’s relative decline. The monument at Qaytbay is a remarkable example of architecture from a time when ornamental arts were at their peak. It used to be a sprawling desert complex with a commercial hub on the main north-south trade route with Syria and the east-west trade route with the Red Sea. The complex of Sultan Qaytbay was built between 1472 and 1474. The sheer number of buildings he commissioned, as well as the delicacy and expertise of workmanship, demonstrated in them, attest to his status as one of Mamluk architecture’s greatest supporters. By Mamluk standards, the construction time was long; however, Qaytbay’s complex was large-scale, encompassing an entire royal sector or walled suburb in what was then a sparsely populated desert graveyard area east of Cairo, now known as the Northern Cemetery. The Burji Mamluks constructed this desert location in the 15th century, when the great southern Qarafa necropolis, let alone the main city, became too crowded for substantial new structures. Not all of the structures that made up Qaytbay’s complex have survived, however, the mosque, which also housed a madrasa and the founder’s mausoleum, is the finest preserved.

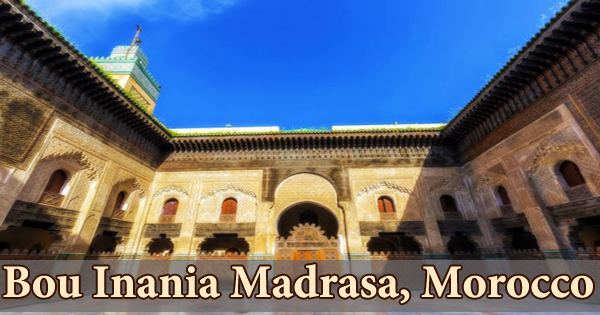

A carved straight-lined star design is placed on another carved network of undulating arabesques on the exterior of the complex’s stone dome. By treating the surfaces of the two systems differently, the contrasting effect is accentuated. The waqf deed identifies the cruciform structure, whose central courtyard is covered by a lantern, as a jami’, despite the inscription on the cruciform structure referring to it as a madrasa. This madrasa-mosque is not dedicated to any specific religious practice. It has two freestanding facades and is, in comparison to many other complexes, a relatively tiny construction. A groin-vaulted trilobed gateway with ablaq inlay and stalactites can be found on the south side. A sabil-kuttab is to the left of the gateway, and a minaret is to the right. A modest yet exquisite mausoleum dome rises from the southeast side of the structure. A carved straight-lined star pattern is overlaid atop another carved network of undulating arabesques on the surface. The minaret, which is magnificently sculpted in stone and divided into three levels with artistically carved balconies, sits above the western entrance. A sabil (from which water might be supplied to passers-by) on the ground level and a kuttab (school) on the top floor occupied the eastern corner of the façade. The complex is the penultimate chapter in the khanqah’s demise as an organization, and it depicts some of the Sufi life standards in late 15th-century Egypt. The khanqah, whose importance in Barsbay’s funeral complex was diluted by two competing zawiyas, is now completely gone. The stone minaret is slender and beautiful, with stars carved in high relief. On the surface, there are two distinct designs, both sophisticated yet distinct. One is a raised straight-lined star design, while the other is a grooved and recessed undulating lacework of floral arabesque. On the neck of the top bulb is a sculpted, twisted band. This is one of Cairo’s most magnificent minarets, and from its tower, one can get a great view of the dome. The sabil, or fountain, features a gilded wooden ceiling and a stone bench and closet with wood and ivory inlaid doors in the entryway. The entrance has another beautiful groin-vault ceiling and leads to the main sanctuary hall, which has a modified madrasa plan with two enormous iwans on the qibla axis and two shallow or reduced iwans on either side. Stone carvings, painted timber ceilings, and colored windows adorn the interior of the hall. The wooden minbar, which is finely carved with geometric designs and inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl, is more modest than the mihrab. The wooden ceiling, which is brightly decorated, and the wooden lantern over the central area were both restored. This ceiling is a lovely example of a composite decoration that incorporates calligraphic, geometric, and arabesque designs, which are the three principal ornamental forms of Islamic art. The center floor has intricate polychrome patterned marble as well, however it is normally covered by carpets. The prayer niche is made of stone and features albaq inlay patterns similar to those found on the gateway conch (a niche with an oval top). The corner recesses of the covered courtyard are adorned with Keel-arched niches with windows. A band of inscriptions runs over the upper space. The mausoleum’s outer dome shows a progression from the stone domes built earlier and nearby by Sultan Barsbay and others: its elaborate stone-carved ornamental pattern is frequently recognized as the peak of Mamluk dome design in Cairo. As a result, this was most likely a typical Friday congregational mosque, with Sufi sessions occurring regularly. Tradition, rather than referring to a specific function, was most likely behind the introduction of the name madrasa. On the inside, a door next to the qibla wall leads to the mausoleum room. A carved and ablaq mihrab, polychrome marble paneling, and a lofty dome with muqarnas pendentives are among the features. Small local mosques began to take on the role of congregational mosques in the late Mamluk period, serving as a multifunctional gathering space for communal prayer, education, and Sufi ceremonies. On the north side of the mosque, there are also the ruins of a drinking trough for animals with keel-arched carved recesses. It’s roofed, and there’s a saqiya, or water wheel, at the back to the right.