The Mosque of al-Zahir Baybars (Arabic: مسجد الظاهر بيبرس) was the first congregational mosque to be established in Cairo after the abolition of the jurisprudence monopoly of Shafi, which confined Friday prayer to a single congregational mosque. It was abandoned for some time and was used in different ways: during the French expedition to Egypt as a military citadel, as a barracks for the Senegalese group of Takrur in the period of Muhammad ‘Alī in 667/June; as a warehouse, a soap-making factory, and during the English occupation as a slaughterhouse. The Comité (heritage committee) began extensive work in 1893 to restore the building to its original function. As an influential king, Sultan al-Zahir Baybars al-Bunduqdari built a strong base for Mamluk rule in Egypt. Baybars had two mosques built in his name in addition to his madrassa, the mosque at Husayniyya, and another larger mosque built in rural southern Cairo in 1273, of which nothing remains. It is a hypostyle mosque whose arcades are deployed in a pattern that alludes to the cruciform layout, incorporating a nine-bay iwan qibla or maqsura identified by piers carrying a wooden dome in front of the mihrab. A long time ago, this dome, which Baybars is said to have ordered the building supervisors to construct with wood from the citadel of Jaffa that he had demolished in 1268, vanished. In 1267 A.D., four years after the development of Baybars’s Madrassa within the middle of the old Fatimid city, Baybars al-Bunduqdari began construction on the mosque at Husayniyya, a district remote from urban life within the northern fringe of Cairo. The mosque, which took a year and a half to complete and cost one million dirhams, was the first Mamluk-era mosque and the first Friday mosque to be constructed in a hundred years’ time in Cairo.

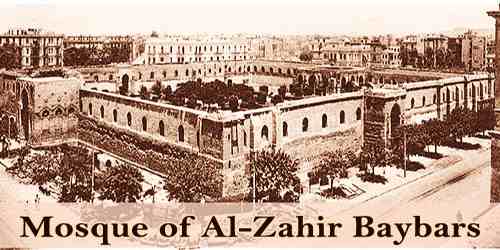

View at The Mosque of Al-Zahir Baybars

The Mosque of al-Zahir Baybars is almost square in form and has three monumental porches opening into a courtyard enclosed by an arcade (three rows to the north-east and south-west, and two rows to the north-west). In order to highlight the devotion of the new dynasty to the philosophy identified with the patrons who founded these foundations, the mosque borrowed visual themes from other historical foundations. The new dynasty found it indispensable to emphasize such a dedication in order to legitimize its new law. Next to the prayer hall is the fourth side of the courtyard, the original plan of which incorporates two separate designs: six naves parallel to the qibla wall, and three transverse naves leading to the mihrāb in the middle. The maqsura mosque is an enclosed area reserved for the monarch in front of the mihrab, and is therefore particularly large under the dome, “almost like an autonomous sanctuary within the mosque.” The dome was colored and marble and glass mosaics depicting trees and other greenery were also decorated with the qibla wall. An immense dome, which was as wide as three naves, resting on pillars and forming a maqsura, preceded the mihrāb. The courtyard is characterized by piers bearing pointed arches and supporting the maqsura dome. The main portal facing the sanctuary is separated by scale and decoration from the two lateral ones on the facade. While the mosque’s exterior is made of stone, the interior is decorated with carved stucco, including stucco grilles in the upper wall’s arched windows, and a Kufic script band that runs around the entire interior. Like the transept in the sanctuary, the roof of the transept that runs from the main portal to the courtyard was raised above the general roof level. Baybars also celebrated his triumphs by adding elements from captured buildings, and indeed his glory can still be seen in the remains of his mosque today on the outskirts of Cairo.