Traditional medicine has a long history of being used to treat a variety of ailments, and researchers are looking into the potential of traditional medicinal plants to combat drug-resistant malaria. Malaria is a potentially fatal disease caused by Plasmodium parasites that are spread through the bite of infected mosquitos. Resistance to commonly used antimalarial drugs has developed in some strains of the malaria parasite over time, posing a significant challenge to malaria control efforts.

Much of what we now call modern medicine evolved from folk remedies or traditional Indigenous practices. These traditions are still practiced today, and they may be useful in dealing with a variety of issues. A team of researchers has identified compounds in the leaves of a specific medicinal Labrador tea plant used by the First Nations of Nunavik, Canada, and demonstrated that one of them has activity against the parasite that causes malaria.

The term “Labrador tea” refers to a group of plants that are all members of the genus Rhododendron. These are small, evergreen shrubs with fuzzy leaves that, as the name implies, are steeped to make herbal teas popular among Inuit and Indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada.

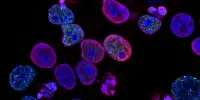

The researchers tested two strains of Plasmodium falciparum, a malaria-causing parasite, to see if the essential oil had antimalarial properties. One of the strains in the experiment was resistant to known antimalarial drugs.

Drinks made from the leaves or roots are said to help treat colds or the flu, headaches or stomach aches, nasal congestion, and a variety of other ailments. Previous research has shown that essential oils extracted from plants have antimicrobial properties, which may aid in the fight against antibiotic-resistant microbes.

Dwarf Labrador tea, or Rhododendron subarcticum, produces an especially aromatic brew and grows in the harsher subarctic conditions found from Alaska to Siberia just south of the Arctic Circle. Despite its widespread use as a traditional medicine, its chemical composition and potential antimicrobial applications have received little attention. As a result, Normand Voyer and colleagues set out to characterize R. subarcticum for the first time and test its antiparasitic activity.

The leaves of R. subarcticum were collected in Nunavik, a region in northern Quebec. The essential oil was extracted from the leaves and analyzed using gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, and flame ionization detection to identify 53 compounds. As it turns out, ascaridole made up 64.7% of the oil, with p-cymene accounting for 21.1%. This combination of compounds has not previously been reported in closely related North American Labrador tea varieties, though it has been found in European and Asian subspecies.

The researchers tested two strains of Plasmodium falciparum, a malaria-causing parasite, to see if the essential oil had antimalarial properties. One of the strains in the experiment was resistant to known antimalarial drugs. According to the findings, ascaridole was the primary component that acted against both strains of the parasite, which is consistent with other antiparasitic traditional medicines that contain the compound. According to the researchers, this study emphasizes the importance of researching and protecting plants used in traditional medicines, particularly those from harsher climates affected by climate change.

Several traditional medicinal plants have shown promising antimalarial properties, and scientists are looking into their potential as drug-resistant malaria treatments. Artemisia annua, also known as sweet wormwood, is one such plant. The plant contains artemisinin, a compound that has been widely used as a key component in modern antimalarial drugs. The emergence of artemisinin-resistant strains of the malaria parasite, on the other hand, has heightened interest in other traditional medicinal plants.