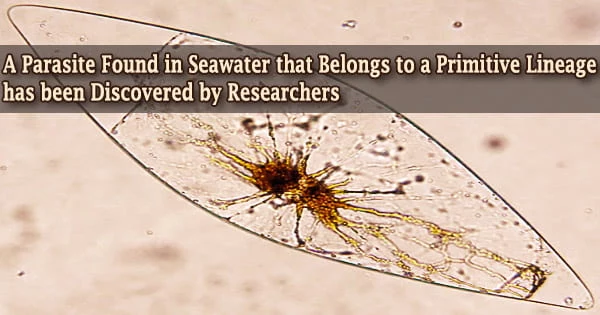

Txikispora philomaios, a parasite found in saltwater and belonging to a primitive lineage, was identified by researchers from the UPV/EHU-University of the Basque Country and CEFAS. This organism will aid in the understanding of how multicellularity arose in mammals.

Phylogenetic and phylogenomic studies utilizing DNA from this parasite are helping researchers better understand the evolutionary changes and adaptations that allowed microscopic unicellular creatures to make the challenging leap to multicellular animals and fungi.

The researcher Ander Urrutia of the UPV/EHU’s Cell Biology in Environmental Toxicology research group and Animal Pathology at CEFAS/OIE, is exploring “the great hidden diversity of unicellular parasitic organisms in the intertidal zone in coastal ecosystems of temperate climates, with the aim of trying to see where they are found, what their ecology is like, how they behave, etc..”

One of the approaches used to attain this goal is environmental DNA (eDNA), which entails “extracting the DNA present in either an organic or environmental matrix, for example, in an organism or previously filtered saltwater samples.”

In particular, Urrutia focused on organisms that parasitize invertebrates: “There are a great many unidentified parasites; we find new DNA sequences and infer their behavior based on their genetic similarity to other parasites, but we don’t really know what they are.”

Txikispora philomaios is a protist (a unicellular eukaryotic organism) that evolved shortly after the division that was undertaken by the common ancestor of animals and fungi before its multicellularity was developed. All the world’s animals and fungi come from the same cellular organism that was presumably present in the ocean hundreds of millions of years ago.

In the process of classifying the unicellular parasites detected in the samples, a researcher from the Department of Zoology and Animal Cell Biology discovered an a priori unknown parasite that did not fit into any existing group based on its characteristics.

“We had to do some molecular analyses which confirmed that it was a different organism. Once we had produced several phylogenetic trees, i.e. after comparing the DNA of this organism with that of its closest possible relatives, we were able to see that it is an organism belonging to a primitive lineage that is close to the point at which animals and fungi became differentiated.”

“It is close to the evolutionary moment when a unicellular organism became differentiated to give rise to all the animals that exist, shortly after which another similar cellular organism was to become differentiated to eventually evolve into all the fungi that exist,” Urrutia explained.

The ‘May-loving spore’

“Txikispora philomaios is a protist (a unicellular eukaryotic organism) that evolved shortly after the division that was undertaken by the common ancestor of animals and fungi before its multicellularity was developed. All the world’s animals and fungi come from the same cellular organism that was presumably present in the ocean hundreds of millions of years ago.”

“At some point it began to aggregate and duplicate itself, while its cells specialized to form tissue, and eventually a body, ranging from a microscopic jellyfish to a huge blue whale,” explained the researcher.

Because parasites’ genetic rearrangement differs from that of their free-living cousins, studying this parasite and its genome will help researchers better understand how animal multicellularity evolved.

“In other words, when and how cells began to communicate with each other, join together, or specialize among themselves, forming increasingly complex organisms. The development of animal multicellularity is very important from the point of view of basic biology,” added Urrutia, who carried out the research at CEFAS in the UK, at the Plentzia Marine Station (PIE) and at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE/CSIC).

As Urrutia explained, “Txikispora is not only a new species, it also gives a name to a new genus, a new family, a new order, and so on. In other words, we now have the new Txikisporidae family, one with quite a few cryptic sequences, i.e. unknown pieces of DNA that look very similar to Txikispora and which could also belong to parasites, although we don’t know where they are or which animals they could parasitize. Many of them are present in aquatic ecosystems in Europe, but we know nothing more about them. That’s another line of research I would like to pursue.”

The researchers at UPV/EHU were tasked with naming this parasite. The term Txikispora was chosen because it is a little spore, and philomaios was chosen since the parasite only emerged for a few days in May, therefore the moniker ‘May-loving spore.’

In addition to the difficulty in placing it phylogenetically in its corresponding group, it was difficult to find it in seawater: “We had been on a wild goose chase until we realized that it is only found in the amphipod community for a few days during this month; it is as if the parasite had disappeared for the rest of the year,” explained Urrutia.

Additional information –

This research is part of Ander Urrutia’s Ph.D. thesis entitled “Cryptic reservoirs of micro-eukaryotic parasites in ecologically relevant intertidal invertebrates from temperate coastal ecosystems” and supervised by Dr. Ionan Marigomez (head of the Plentzia Marine Station PiE) and Dr. Stephen W. Feist of the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science CEFAS (United Kingdom). Iñaki Ruiz-Trillo from IBE-CSIC in Barcelona also collaborated in the study.