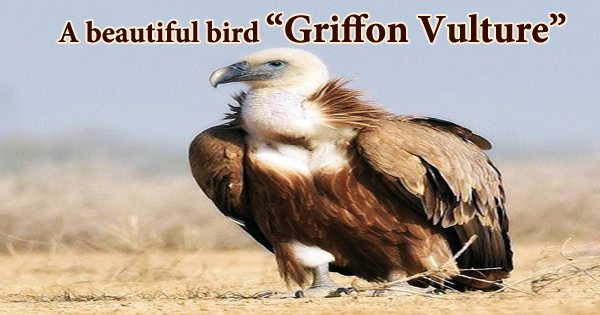

The griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus), also called the Eurasian Griffon, is a large Old-World vulture belonging to the Accipitridae family of birds of prey. It is Europe’s second-largest bird, a rare form of vulture eagle with an astonishing size and up to a 3m wingspan. It is not to be confused with Rüppell’s griffon vulture (Gyps rueppellii), which is a separate species. It looks a lot like the white-backed vulture (Gyps africanus). Following a fall in the twentieth century due to poisoning, hunting, and dwindling food supplies, the species has recently exploded in some locations, particularly in Spain, the French Pyrenees, and Portugal. The breeding population in Europe is estimated to be between 19.000 and 21.000 pairs, with around 17.500 pairs in Spain and about 600 in France. This huge short-tailed vulture has excellent eyesight and can locate an animal carcass from more than five kilometers away when flying. It can be observed majestically soaring on thermal currents in search of food in the warmer, more rugged areas of the Mediterranean’s surrounding countries. It wears a creamy-white ruff that matches the hue of its head and neck. Its pale brown body and upper-wing feathers contrast nicely with its dark flight feathers and tail; the contrast is especially obvious in young birds, whose upper-wing feathers are exceptionally pale. The griffon vulture measures 93–122 cm (37–48 in) in length and has a wingspan of 2.3–2.8 m (7.5–9.2 ft). Males normally weigh 6.2 to 10.5 kilograms (14 to 23 lb) in the nominate race, whereas females normally weigh 6.5 to 10.5 kg (14 to 23 lb) in the Indian subspecies (G. f. fulvescens) (16 lb). Mountains, plateaus, shrubland, grassland, and semi-desert habitats are home to these birds, who prefer warm climes but will even tolerate cold, rain, mist, and snow in order to gain exceptionally ideal nesting or feeding conditions. Forests, lakes, marshes, and marine waterways are places they tend to avoid. They roost on steep cliffs and can be found at a variety of heights.

The griffon vulture is one of Europe’s largest birds and a master of the air. Adult birds have a white head, neck, and ruff-like collar that resembles feathers. Adult weights of 4.5 to 15 kg (9.9 to 33.1 lb) have been documented, with the latter possibly obtained in captivity. Griffon vultures are a diurnal species that forage together by circling a certain region while keeping an eye on another vulture until the food is seen, at which point a large group of birds may alight to eat on the dead carcass. As each bird attempts to preserve its position, this may include impressive threat shows and combat. The wingtips are deeply fingered in flight. Although the collar is brown and the back is deeper in color, juveniles look identical to adults. Griffon vultures eat the softer components of carcasses, such as muscles and viscera. This species can reach deep within the carcass without snagging because of its long neck. In comparison to other vulture species, Griffon vultures are particularly social. They feed and breed in colonies on rocky cliffs in groups. For an individual in captivity, the griffon vulture has a maximum lifespan of 41.4 years. Griffon vultures are quite loud, using a range of cries to communicate with other members of their species. When dominating birds are feeding, they make a long hissing sound, and when another bird gets too close, they make a wooden-sounding chattering sound. Griffon vultures like open areas such as cliffs and gorges, as well as alpine regions and lowland terraces. They are excellent flyers, catching thermal air currents and flying long distances. Often observed circling high in the air on a thermal in search of food while being watched by and watching other griffon vultures for signs of carrion. Griffon vultures breed in colonies of 15 to 20 pairs, though up to 150 pairs have been seen. They use 1-2 cm diameter sticks, finer twigs, and grasses to construct their nest on a cliff-face in a rock cavity or on a protected ledge where a human would have difficulties accessing. Between December and March, one egg is deposited and incubated for fifty to fifty-eight days by both parents. Both adults feed the chicks, and they fledge one hundred and twenty days after hatching. Often, parents will continue to feed their fledged children for another three months. The Griffon vulture has not considered a globally threatened species due to its huge breeding range and population. It does, however, face a number of dangers, including poisoned corpses placed by farmers to decrease predator numbers. Illegal persecution, particularly by poisoning, is a severe issue in some countries, such as the Balkans and Spain. Food scarcity caused by the removal of deceased animals (cows, sheep, and pigs) from the countryside can likewise pose a hazard to people. The Griffon vulture has a one-of-a-kind role in the food chain, making it indispensable. It specialized in consuming deceased animals, preventing disease transmission, and assisting with “natural recycling.”