Researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania claim that an experimental mRNA-based vaccine against all 20 known subtypes of influenza virus offered extensive protection from otherwise deadly flu strains in initial tests and might one day be used as a general preventative measure against upcoming flu pandemics.

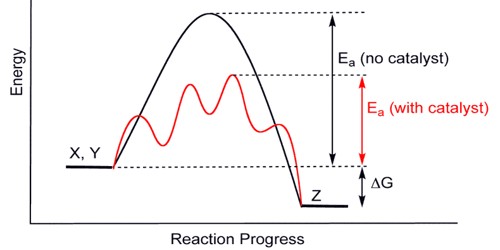

The “multivalent” vaccine, which the researchers describe in a paper published today in Science, uses the same messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) technology employed in the Pfizer and Moderna SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

This mRNA technology that enabled those COVID-19 vaccines was pioneered at Penn. Even when the animals were exposed to flu strains distinct from those employed in the vaccine’s development, tests on animal models revealed that the vaccine significantly decreased symptoms and protected against death.

“The idea here is to have a vaccine that will give people a baseline level of immune memory to diverse flu strains, so that there will be far less disease and death when the next flu pandemic occurs,” said study senior author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor in of Microbiology at in the Perelman School of Medicine.

Drew Weissman, MD, PhD, the Roberts Family Professor in Vaccine Research and Director of Vaccine Research at Penn Medicine, and his team, a pioneer in mRNA vaccine research, worked together on the project with Hensley and his lab.

Influenza viruses periodically cause pandemics with enormous death tolls. The most well-known of them was the “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918-19, which claimed the lives of at least tens of millions of people around the world.

It would be comparable to first-generation SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines, which were targeted to the original Wuhan strain of the coronavirus. Against later variants such as Omicron, these original vaccines did not fully block viral infections, but they continue to provide durable protection against severe disease and death.

Professor Scott Hensley

Pandemics can begin when one of these strains of flu virus leaps to people and picks up modifications that make it better suited for spreading among humans. Flu viruses can circulate in birds, pigs, and other animals.

The “seasonal” flu vaccines available today only provide protection against strains that have recently been circulating; they do not, therefore, provide protection against novel, pandemic strains.

The Penn Medicine researchers’ method is to immunize utilizing immunogens, a kind of antigen that triggers immune responses against all recognized influenza subtypes in order to produce broad protection.

It is not anticipated that the vaccination would deliver “sterilizing” immunity that entirely shields against viral infections. The new study instead demonstrates that the vaccination induces a memory immune response that can be swiftly recalled and tailored to new pandemic viral strains, thereby considerably lowering severe sickness and infection-related death rates.

“It would be comparable to first-generation SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines, which were targeted to the original Wuhan strain of the coronavirus,” Hensley said. “Against later variants such as Omicron, these original vaccines did not fully block viral infections, but they continue to provide durable protection against severe disease and death.”

When administered and absorbed by recipients’ cells, the experimental vaccine begins to produce copies of the hemagglutinin protein, a crucial component of the influenza virus, for all twenty influenza hemagglutinin subtypes H1 through H18 for influenza A viruses and two more for influenza B viruses.

“For a conventional vaccine, immunizing against all these subtypes would be a major challenge, but with mRNA technology it’s relatively easy,” Hensley said.

The mRNA vaccination strongly responded to all 20 flu subtypes in mice and produced high levels of antibodies that persisted at elevated levels for at least four months. Furthermore, the vaccination appeared to be generally unaffected by previous exposures to the influenza virus, which can alter immune reactions to conventional influenza vaccines. Whether or not the mice had previously been exposed to the flu virus, the researchers saw a strong and widespread antibody response in the mice.

Hensley and his colleagues currently are designing human clinical trials, he said. The vaccine may be helpful for inducing long-term immunological memory against all influenza subtypes in people of all age groups, including young children, if those studies are effective, according to the researchers.

“We think this vaccine could significantly reduce the chances of ever getting a severe flu infection,” Hensley said.

“In principle,” he added, “the same multivalent mRNA strategy can be used for other viruses with pandemic potential, including coronaviruses.”