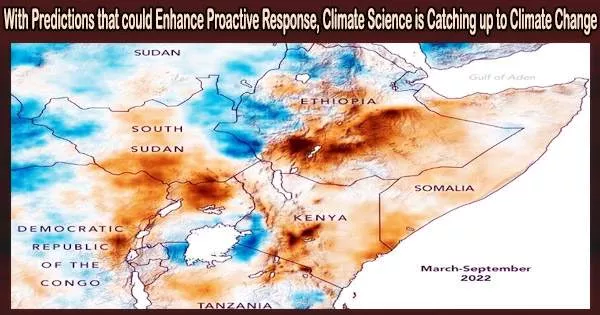

Extreme weather conditions like drought and flooding are examples of how climate change is being felt in Africa. It has been possible to predict and monitor these climatic events, providing early warning of their impacts on agriculture to support humanitarian and resilience programming in the world’s most food insecure nations, thanks to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (which draws on knowledge from USG science agencies, universities, and the private sector).

Science is beginning to catch up with and even get ahead of climate change. In a commentary for the journal Earth’s Future, UC Santa Barbara climate scientist Chris Funk and co-authors assert that predicting the droughts that cause severe food insecurity in the Eastern Horn of Africa (Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia) is now possible, with months-long lead times that allow for measures to be taken that can help millions of the region’s farmers and pastoralists prepare for and adapt to the lean seasons.

“We’ve gotten very good at making these predictions,” said Funk, who directs UCSB’s Climate Hazards Center, a multidisciplinary alliance of scientists who work to predict droughts and food shortages in vulnerable areas.

According to a prediction made by the CHC for the summer of 2020, the Eastern Horn of Africa would see a disastrous succession of droughts due to climate change and naturally occurring La Nia occurrences. The region normally has two wet seasons a year spring and fall. An unprecedented five rainy seasons in a row failed. The CHC had forecast droughts for each of those failures eight months beforehand.

“Fortunately, agencies and other collaborators paid heed to those early warnings and were able to take effective actions,” Funk said. “Within the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the forecasts helped motivate hundreds of millions of dollars in assistance for millions of starving people.”

These initiatives were a far cry from the identical drought projections the researchers made for the same region ten years earlier in collaboration with the USAID-supported Famine Early Warning Systems Network. Predictions that went largely unheeded. “More than 250,000 Somalis died,” Funk said. “It was just really horrible.”

He claimed that at the time, rainfall shortages in this region couldn’t be predicted by the forecasts that were at hand. Models predicted that East Africa would have more rainfall, however observations during the rainy season in the spring indicated dramatic decreases. To be fair, he said, the team’s ability to anticipate the weather over a lengthy period of time were still developing.

To reduce the impacts of climate extremes, we need to look for opportunities. We need to pay attention to not just how climate is changing, but how these changes can support more effective predictions for droughts and for advantageous cropping conditions. As a community, we also need to foster communication about successful resilience strategies.

Laura Harrison

“We made an accurate forecast, but we didn’t understand very well what was going on scientifically,” Funk said. “Now, following our success in 2016/17, and extensive outreach efforts, the humanitarian relief community appreciates the value of our early warning systems.”

The researchers have spent the last ten years trying to identify and comprehend the vast, frequently immeasurable dynamics that fuel drought in the Eastern Horn of Africa and developing precise, specialized forecasts for the area. They built on studies demonstrating that higher rainfall in Indonesia, brought on by human-caused rises in sea surface temperatures, resulted in less moisture flowing onto the East African coast during the rainy months.

These changes in moisture flows drive back-to-back droughts. However, as sea surface temperatures in the western Pacific warm due to climate change, it is getting easier to foresee dire water shortages.

“We’ve published about 15 scientific papers on this topic,” Funk said, “and we’ve forecasted dry seasons in 2016-2017, which helped prevent a famine that year.” As he discusses in his book “Drought, Flood, Fire (Cambridge University Press, 2021),” “climate change amplifies natural sea surface temperature variations, which opens the door to better forecasts.”

The co-authors stress, in the new commentary and a larger work that is currently in preprint stage and will also appear in Earth’s Future, the prospects connected to these long-term outlooks and the physical principles underlying the predictability.

“To reduce the impacts of climate extremes, we need to look for opportunities,” said CHC Specialist and Operations Analyst Laura Harrison. “We need to pay attention to not just how climate is changing, but how these changes can support more effective predictions for droughts and for advantageous cropping conditions. As a community, we also need to foster communication about successful resilience strategies.”

“Flooding still happens, drought still happens, people still get hurt, but we can try to reduce the harm.”

With the help of weather forecasts that can make projections at two weeks and 45 days in advance as well as climate models that can predict extreme ocean states eight months in advance, CHC scientists and researchers can now give collaborators on the ground useful information to assist local farmers in anticipating and preparing for dry conditions.

“We’re working with this group called Plant Village, who is providing agricultural advisories to millions of Kenyans, and helping them take actions that can help make their crops more drought-resistant,” Funk said.

This proactivity is something Funk and collaborators hope will become a bigger part of climate change strategy for the Eastern Horn of Africa, as their models predict more of these drought-forming conditions in the region’s future.

A better local understanding of the mechanisms that result in droughts, and investments in early warning systems and adaptation measures, may initially be costly, they said, “but are relatively inexpensive when compared to post-impact, response-based alternatives such as humanitarian assistance and/or funding safety-net programs.”

Education and participation can build trust and ultimately increase resilience. In order to fuel collaborations in other parts of the world, the CHC is expanding on what they learnt in East Africa.

In southern Africa, for example, they are collaborating with the Zimbabwe Meteorological Services Department and the Knowledge Impact Network to support the development of actionable climate services.

“Understanding that climate change makes extremes more frequent is really empowering because now we can try to anticipate those bad effects,” Funk said. “Flooding still happens, drought still happens, people still get hurt, but we can try to reduce the harm.”