After getting preliminary approval from Japan’s nuclear authority, the proposal to dump radioactive effluent from the remains of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant into the ocean appears to be more feasible than ever. Following a decision by Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) to allow a one-month public comment period on the plan, the proposal to release treated wastewater from the nuclear plant into the Pacific, which was passed as a bill by the Japanese Cabinet in August last year, took another big step forward on Wednesday. After the public comment period ends on June 18, the NRA will grant its official permission for the proposal to move forward next year.

TEPCO, the power plant operator, intends to begin releasing the radioactive water from the site after treatment into the ocean in spring 2023, if it receives the ultimate green light, as many predict. It’s been more than 11 years since the Fukushima nuclear disaster on March 11, 2011, which became one of the worst nuclear disasters in history. It all began when a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck Japan’s east coast, unleashing a deadly tsunami. When the tsunami struck the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, three reactor cores lost power. The three cores melted down due to a lack of power to the cooling, releasing large quantities of radiation into the surrounding environment.

Hundreds of tanks carrying about 1.25 million tons of polluted water used to cool the reactors during the incident are among the many problems left behind by the tragedy. Local residents and several members of the international community have expressed concern over the proposal to release polluted water into the sea, highlighting concerns about the impact on ecosystems and human health.

Several analyses and studies, however, have shown that the plan is safe. The idea was investigated by the International Atomic Energy Agency earlier this year, and it was found in April that Japan had made significant progress with its proposed water discharge, but that more information was needed before it could be executed. The polluted water is treated to eliminate the bulk of radioactive components, leaving tritium, one of two radioactive forms of hydrogen, behind. While tritium is hazardous, it is a naturally occurring element, and scientists believe the amount in the ecosystem will be minimal once diffused over the ocean.

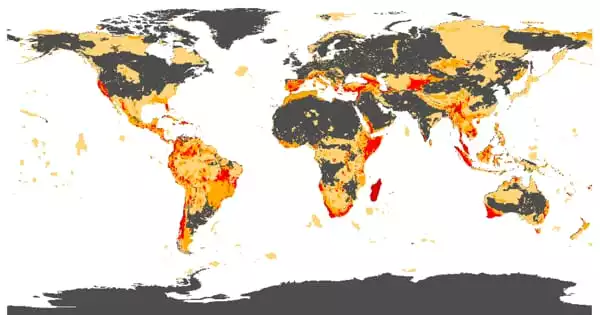

It’s just one of the least dangerous radionuclides; in fact, it’s the substance used to make wristwatches light in the dark. According to a report published earlier this year that modeled how radioactive water will disperse throughout the world’s seas, the contaminants will blanket practically the entire North Pacific area within 1,200 days, reaching as far east as the coast of North America and as far south as Australia. The contaminants will blanket practically the whole Pacific Ocean by day 3,600. The tritium is expected to last up to 40 years in the water, although it will be much diluted in the enormous Pacific Ocean.