Magnificent Rebels by Andrea Wulf tells the story of a group of romantics men and women who were philosophers, artists, poets, scientists, and engineers who lived, loved, and worked in Jena around the year 1800.

Wulf cites one of the romantics, the poet Novalis, who came up with the symbol of inspiration of the blue flower, with his definition of what romanticism is: “By giving the commonplace a higher meaning, by making the ordinary look mysterious, by granting to what is known the dignity of the unknown and imparting to the finite a shimmer of the infinite, I romanticize” (p. 164).

Remember that the word “romantic” originally meant “the novel,” or “le roman,” in French and Der Roman in German. It is about leading a life that is deserving of being the subject of a gripping story.

The romantic movement, which fused poetry and science, criticized the materialism worldview of the day, which held that the universe was nothing more than an impersonal machine according to the exact physical rules of nature. Any form of wonder or spirituality had been stripped away by the physicalist conviction.

More than 220 years later, this scientific worldview still rules. It is arguably best shown by the frequently cited claims made by neuroscientists and philosophers alike that only cerebral processes, and nothing else, can account for thoughts and feelings.

The illusion of consciousness perception is reduced to brain activity. Understanding the brain will teach us everything there is to know about what it means to be a person. This intellectual position essentially seeks to eliminate phenomenal consciousness, that which is primary and immediate.

Because consciousness, which is supposed to exist for reductionist physicalists as well, has not yet been adequately explained by science, it is either a myth or just an illusion. The British philosopher Galen Strawson in his article, “A hundred years of consciousness: a long training in absurdity” mocks the “most remarkable episode in the history of human thought” in that such thinkers deny the existence of what everyone knows with certainty to exist: conscious experience.

The problem of consciousness is so strikingly different from all other scientific problems (concerned with the objective world) that deniers want to argue it away: It does not exist. I once attended a talk by a philosopher who stated with fervor that he was a physicalist as if he had said that he was a political activist for a certain cause or a supporter of the F.C. Liverpool. It sounded a lot like a point of view he had to defend against heretics who continue to believe that awareness is a real thing that exists in the world.

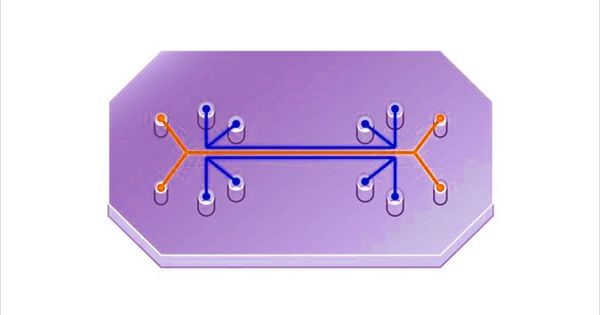

Why would I mention the romantics in relation to the 21st-century consciousness-brain problem? The difficult question of consciousness how neuronal activity would give rise to experience has eluded brain science up to this point. Between phenomenal awareness, or the first-person perspective of what it is like to have an experience, and the level of neuronal processes (the objective perspective), there is still an insurmountable distance.

Anil Seth in his book Being You eloquently summarizes some of the recently developed theories of consciousness. Yet, all the attempts are about the easy problem of consciousness, i.e. how neural systems function when “somehow” correlating with conscious experience. Related, see my Psychology Today post, “Why Most Neuroscientific Theories of Consciousness Are Wrong.”

Nobody has an idea as to how subjective feelings can be derived from matter. Whatever neuroscientists and physicists may claim, they are unable to explain how consciousness arises, why it is uniformly reported by people, and why it must consequently exist in the cosmos.

Why not start a new romantic movement that gives “the commonplace a higher meaning, by making the ordinary look mysterious, by granting to what is known the dignity of the unknown and imparting to the finite a shimmer of the infinite”?

We should all romanticize since nobody knows how consciousness develops, it is so commonplace, has a deeper meaning for us, is enigmatic, and has the dignity of the unknown.

In her book Conscious, Annaka Harris gives the reader some recent scientific theories about the potential outcomes of such a journey. We have to think out of the box if we want to understand consciousness.

The romantics from 1800, by the way, were deeply interested in science. They wanted to integrate science and poetry. The philosopher F.W.J. Schelling in 1801 believed that the conscious inner light we experience is part of nature. I and nature are one, two different sides of the same coin.

In modern terms, consciousness is brain activity from within. Similar to how Galen Strawson argued, if physical rules govern everything, then consciousness would also fall under their purview that is, physics as seen from the first-person perspective.

There are many commonalities between Schelling, romantics, and proponents of some current theories. The world is still mysterious. Science will make progress with a breeze of romanticism.

Note: The German philosopher and romantic F.W.J. Schelling had several intuitive ideas on consciousness, which modern psychological and neuroscientific concepts seem to share, let alone my own.

In my Psychology Today blog, “The Mystery of Subjective Time: A Case for Embodiment,” I argue for the strong connection between the sense of time and feelings of the bodily self, based on phenomenology and functional brain research. The sense of self and time are intricately bound. That is exactly what Schelling wrote in 1800: “Time is not something that runs independently of the I, but the I is time conceived in activity.”