The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest ocean in the world, covering approximately 41 million square miles (106 million square kilometers) and separating the continents of North America and South America from Europe and Africa. About 55 million years ago, the Atlantic Ocean was born. Until then, Europe and America were connected. It stretches from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south and is bordered by various countries and island nations.

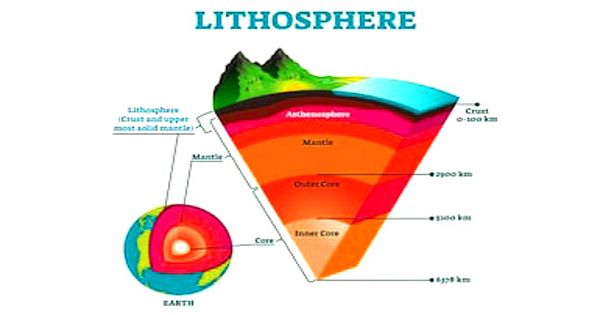

The Earth’s crust between the continents split as they started to separate, releasing massive amounts of lava. This rift volcanism has led to the formation of large igneous provinces (LIPs) in several places around the world.

One such LIP was formed between Greenland and Europe and now lies several kilometers below the ocean’s surface. An international drilling campaign led by Christian Berndt from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, and Sverre Planke from the University of Oslo, Norway, has collected extensive sample material from the LIP, which has now been evaluated.

In their study, published today, August 3, 2023, in the journal Nature Geoscience, Researchers have demonstrated that hydrothermal vents were active at very shallow depths or even above sea level, allowing for much greater atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases than was previously believed.

“At the Paleocene-Eocene boundary, some of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in Earth’s history took place over a period of more than a million years,” says Christian Berndt.

According to current knowledge, this volcanism warmed the world’s climate by at least 5°C and caused a mass extinction the last dramatic global warming before our time, known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). Geologists have not yet been able to explain why, as most modern volcanic eruptions cause cooling by releasing aerosols into the stratosphere.

Additional research into the South African Karoo big igneous province found a huge number of hydrothermal vents linked to magmatic intrusions into the sedimentary basin. This and other observations prompted the theory that hydrothermal venting may have allowed significant quantities of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and methane to reach the atmosphere.

At the Paleocene-Eocene boundary, some of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in Earth’s history took place over a period of more than a million years.

Christian Berndt

“When our Norwegian colleagues Henrik Svensen and Sverre Planke published their results in 2004, we would have loved to set off immediately to test the hypothesis by drilling the ancient vent systems around the North Atlantic,” says Christian Berndt. But it wasn’t that easy. “Our proposal was well received by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP), but it was never scheduled because it required riser drilling, a technology that was not available to us at the time.”

Riserless drilling-capable hydrothermal vent systems were found as the investigation moved further. Thus, the drilling proposal was resubmitted, and the expedition could finally begin in autumn 2021-17 years after the first proposal was submitted.

Around 30 scientists from 12 nations took part in the IODP (now the International Ocean Discovery Program) research cruise to the Vøring Plateau off the Norwegian coast on board the scientific drilling ship “JOIDES Resolution.”

Five of the 20 boreholes were drilled directly into one of the thousands of hydrothermal vents. Scientists like a diary of the Earth’s history can read the cores obtained. The results were compelling.

The researchers demonstrate that the vent was operational shortly prior to the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum and that the crater it left behind was quickly filled in, coinciding with the onset of global warming. Unexpectedly, their results also demonstrate that the vent was active in water that was likely no deeper than 100 meters. This has far-reaching consequences for the potential impact on the climate.

Berndt states, “Most of the methane that enters the water column from active deep-sea hydrothermal vents today is quickly converted into carbon dioxide, a much less potent greenhouse gas. Since the vent we studied is located in the middle of the rift valley, where the water depth should be greatest, we assume that other vents were also in shallow water or even above sea level, which would have allowed much larger amounts of greenhouse gases to enter the atmosphere.”

There are several intriguing inferences that can be made from the cores on the current global warming. On the one hand, they do not prove that the gas hydrate hazard, which has been heavily addressed in recent years, was the source of the global warming at that time.

On the other hand, they demonstrate that it took several centuries for the climate to return to a cooling trend. The Earth system was thus capable of self-regulation, though not on timescales pertinent to the current climate problem.