Vitamin deficiency anemia is characterized by a shortage of healthy red blood cells produced by low levels of vitamin B-12 and folate. This can occur if you do not consume enough vitamin B-12 and folate-containing foods, or if your body has difficulty absorbing or processing these vitamins. In the absence of these nutrients, the body forms red blood cells that are excessively big and do not function properly. This decreases their oxygen-carrying capacity.

Vitamin deficiency is the absence of a vitamin for an extended period of time. A primary deficit is caused by insufficient vitamin consumption, but a secondary deficiency is caused by an underlying condition such as malabsorption. An underlying problem could be metabolic, such as a genetic flaw in converting tryptophan to niacin, or it could be caused by lifestyle decisions that increase vitamin requirements, such as smoking or consuming alcohol. Government vitamin deficiency standards recommend precise vitamin intakes for healthy persons, with specific values for women, men, babies, the elderly, and during pregnancy or breastfeeding. To address commonly occurring vitamin deficiencies, many governments have required vitamin food fortification programs.

Hypervitaminosis, on the other hand, refers to symptoms induced by vitamin intakes that exceed requirements, particularly for fat-soluble vitamins that can accumulate in human tissues. Low vitamin consumption can lead to deficiency, and a number of medical problems can predispose you to vitamin insufficiency. Blood testing can reveal vitamin deficiency. They can also be rectified with oral (by mouth) or injectable vitamin supplements.

The discovery of vitamin deficiencies progressed over centuries, from observations that certain illnesses, such as scurvy, might be prevented or cured with certain foods high in a vital vitamin, to the identification and description of specific molecules important for life and health. During the 20th century, several scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine or the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their roles in the discovery of vitamins.

Several areas, including Japan, the European Union, the United States, and Canada, have released guidelines diagnosing vitamin inadequacies and advising particular intakes for healthy adults, with varying recommendations for women, men, infants, the elderly, and during pregnancy and breast feeding. As new research is published, these documents are updated. The Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences established the first Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) in the United States in 1941. Periodic modifications were made, culminating in the Dietary Reference Intakes.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) produced a set of tables in 2016 that describe Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and (RDAs). RDAs are higher to accommodate persons with greater-than-average demands. These are all part of the Dietary Reference Intakes. There is insufficient information to set EARs and RDAs for a few vitamins. An Adequate Intake is shown for these, based on the assumption that what healthy people consume is sufficient. Countries do not always agree on the amount of vitamins required to prevent deficiency. For example, the RDAs for vitamin C for women in Japan, the European Union, and the United States are 100, 95, and 75 mg/day, respectively. The Indian government recommends 40 milligrams each day.

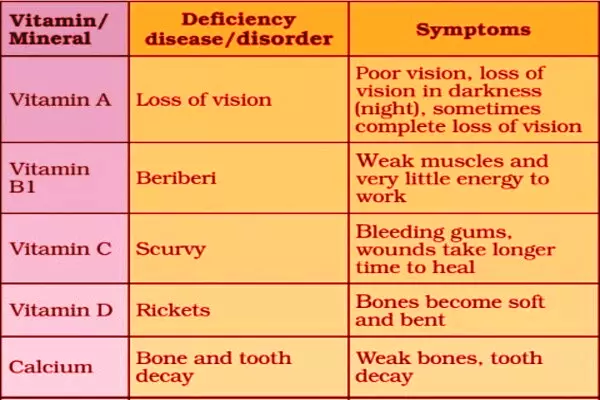

Vitamin deficiencies continue to be widespread throughout the world. They are frequently clinically undiagnosed unless severe, although even modest deficiency can have serious implications. Vitamin shortages affect people of all ages and frequently coexist with mineral deficiencies (zinc, iron, iodine). Because of their relatively high demands for these compounds and susceptibility to their absence, pregnant and lactating women and young children are the groups most vulnerable to vitamin deficiencies. These include infectious disease death, anemia, pregnancy or childbirth death, and poor mental and physical development.