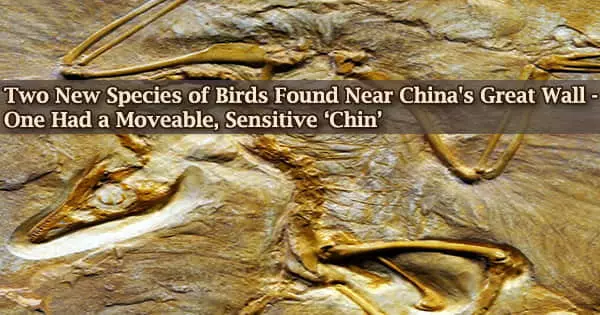

Paleontologists discovered evidence of an even older planet around 80 miles from the westernmost reach of China’s Great Wall. Over the previous two decades, scientists have discovered more than 100 fossil birds from the period of the dinosaurs, which lived about 120 million years ago.

Many of these fossils, however, have proven difficult to identify since they are fragmentary or heavily crushed. Researchers analyzed six of these fossils and discovered two new species in a new report published in the Journal of Systematics and Evolution. One of the new species featured a moveable bony attachment at the tip of its lower jaw, which could have assisted the bird in rooting for food.

“It was a long, painstaking process teasing out what these things were,” says Jingmai O’Connor, the study’s lead author and the associate curator of vertebrate paleontology at Chicago’s Field Museum. “But these new specimens include two new species that increase our knowledge of Cretaceous bird faunas, and we found combinations of dental features that we’ve never seen in any other dinosaurs.”

“These fossils come from a site in China that has produced fossils of birds that are pretty darned close to modern birds, but all the bird fossils described thus far haven’t had skulls preserved with the bodies,” says co-author Jerry Harris of Utah Tech University. “These new skull specimens help fill in that gap in our knowledge of the birds from this site and of bird evolution as a whole.”

All birds are dinosaurs, but not all dinosaurs are birds; a small subset of dinosaurs evolved into birds during 90 million years of coexistence with other dinosaurs. Modern birds are descended from a group of birds that survived the extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs, although many prehistoric birds perished as well.

O’Connor’s research focuses on diverse types of early birds to see why some survived and others died out. Changma, a fossil site in northeastern China, is crucial to academics like O’Connor who study bird evolution.

At a time when giant dinosaurs still roamed the land, these birds were the products of evolution experimenting with different lifestyles in the water, in the air, and on land, and with different diets as we can see in some species having or lacking teeth. Very few fossils of this geological age provide the level of anatomical detail that we can see in these ancient bird skulls.

Tom Stidham

It’s the world’s second-richest Mesozoic (Dinosaur Age) bird fossil site, although more than half of the fossils discovered there are from the same species, Gansus yumenensis.

It’s difficult to tell which fossils are Gansus and which aren’t; the six specimens reviewed by O’Connor and her colleagues are mostly skulls and necks, which aren’t preserved in known Gansus specimens. The fossils had also been smushed by their time down underground, making analysis difficult.

“The Changma site is a special place,” says study co-author Matt Lamanna of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “The fossil-bearing rocks there tend to split into thin sheets along ancient bedding planes. So, when you’re digging, it’s like you’re literally turning back the pages of history, layer by layer uncovering animals and plants that haven’t seen the light of day in roughly 120 million years.”

“Because the specimens were pretty flattened, CT-scanning them and fully segmenting them could take years and might not even give you that much information, because these thin bones are flattened into almost the same plane, and then it just becomes almost impossible to figure out where the boundaries of these bones are,” says O’Connor. “So we had to kind of work with what was exposed.”

The researchers were able to identify critical traits in the birds’ jaws through meticulous work, revealing that two of the six species were previously unknown to science.

Meemannavis ductrix and Brevidentavis zhangi are the names of two new species (or, more technically, genera; a genus is a step above a species in the order scientists employ to name animals). Meemannavis is named after Meemann Chang, a Chinese paleontologist who led the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing for the first time. The name Brevidentavis means “short-toothed bird.”

Meemannavis and Brevidentavis, like Gansus, are ornithuromorph birds, which include modern birds. Meemannavis had no teeth, like like today’s birds. Brevidentavis, on the other hand, had a mouth full of short, peg-like teeth packed tightly together. Along with those teeth, there was another oddity.

“Brevidentavis is an ornithuromorph bird with teeth, and in ornithuromorphs with teeth, there’s a little bone at the front of the jaw called the predentary, where its chin would be if birds had chins,” explains O’Connor.

By CT-scanning the bone and coloring it with chemicals, the authors discovered that the predentary bone endured stress, as well as a type of cartilage that only forms when there is movement, in a prior work on the predentary in another fossil bird.

“In this earlier study, we were able to tell that the predentary was capable of being moved, and that it would have been innervated Brevidentavis wouldn’t just have been able to move its predentary, it would have been able to feel through it,” says O’Connor. “It could have helped them detect prey. We can hypothesize that these toothed birds had little beaks with some kind of movable pincer at the tip of their jaws in front of the teeth.”

Brevidentavis isn’t the first fossil bird to be discovered with a predentary that may have been utilized in this way, but its discovery, together with that of Meemannavis, adds to our knowledge of prehistoric bird diversity, particularly in the Changma region.

The research also sheds light on Gansus, the most prevalent bird at the site, as at least four of the other specimens analyzed are most likely of this species.

“Gansus is the first known true Mesozoic bird in the world, as Archaeopteryx is more dinosaur-like, and now we know what its skull looks like after about 40 years,” notes Hai-Lu You of the IVPP.

“These amazing fossils are like a lockpick allowing us to open the door to greater knowledge of the evolutionary history of the skull in close relatives of living birds,” says Tom Stidham, a co-author from the IVPP.

“At a time when giant dinosaurs still roamed the land, these birds were the products of evolution experimenting with different lifestyles in the water, in the air, and on land, and with different diets as we can see in some species having or lacking teeth. Very few fossils of this geological age provide the level of anatomical detail that we can see in these ancient bird skulls.”

“These discoveries strengthen the hypothesis that the Changma locality is unusual in that it is dominated by ornithuromorph birds, which is uncommon in the Cretaceous,” says O’Connor. “Learning about these relatives of modern birds can ultimately help us understand why today’s birds made it when the others didn’t.”