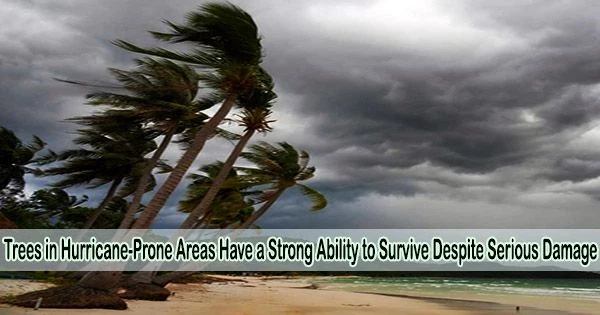

Researchers from Harvard and Clemson universities gazed out the window as their low-flying aircraft approached the airport on the island of Dominica and noticed kilometers of woodlands full with matchstick-shaped trees.

It had been nine months after Category 5 Hurricane Maria had directly struck the West Indies island.

While 89% of the trees had damage, 76% of which had serious damage, the researchers found that just 10% were instantly killed when they actually entered the forests and looked at the trees more closely. Numerous trees had grown new growth.

“These hurricane-prone forests are, in many regards, incredibly resistant to even extremely powerful hurricanes. I don’t want to minimize the scale of damage that these forests received it was immense but the fact that 90% of the trees survived shows an impressive level of resistance,” said Benton Taylor, a former graduate student in the Clemson Department of Biological Sciences who is now an assistant professor in the Harvard University Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology.

With climate change, hurricanes are increasing in frequency and severity. Numerous areas of the world that are frequently affected by hurricanes also play crucial roles in the global “hotspots” of biodiversity and the cycling of carbon, water, and nutrients.

Hurricane Maria hit Dominica on September 18, 2017, with winds topping 160 mph the strongest hurricane on record to make landfall there. Days later, Maria devastated the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico.

With funding from the Clemson Caribbean Initiative, Department of Biological Sciences Chair Saara DeWalt, Taylor and Dominican researcher Elvis Stedman remeasured and assessed damage of all the trees in nine forest stands across Dominica.

In a field where opportunities to study a phenomenon are rare hurricanes themselves are rare events and it’s even rarer that one hits a forest plot that was measured before the hurricane hit any additional data are useful. That said, our study highlights that the effects of hurricanes can be very different based on the local topography and tree species that make up a forest. So comparing a small mountainous island populated by tropical rainforest trees to the forests of the coastal plains and piedmont regions of the southern United States should be approached with caution.

Benton Taylor

The plots were established in 2006 by DeWalt and former Clemson researcher Kalan Ickes. In order to assess biomass and calculate how much carbon had been transferred from living to dead by the hurricane, they also evaluated wood density and carbon content for the 44 most prevalent tree species.

They discovered that stem snapping (which occurred in 40% of trees) and substantial branch damage (26% of trees) were the damage kinds that occurred most frequently, but that uprooting and being crushed by a neighboring tree had the highest rates of mortality. Thirty-three percent of uprooted trees and 47% of trees that were crushed died.

“Snapping wasn’t as lethal as you might think,” said DeWalt, a senior researcher on the study.

Larger trees individually and species with less dense wood were more prone to snapping, uprooting, and death. Trees on steeper slopes were more prone to being crushed by neighboring trees.

“More frequent storms will shape the structure and composition of forests in hurricane-prone regions,” DeWalt said. She expects that they’ll shift toward smaller, high wood-density species.

“Forests are adapted to this kind of disturbance, but we may see a shift in the types of species that are most common in these forests with increasing frequency of strong hurricanes. You might get more of the ‘live fast, die young’ species because you’re constantly resetting the forest,” she said.

“Fewer big, old trees could impact wildlife,” Taylor said. “Two parrots native to Dominica the Sisserou and Jaco, both of which occur only on this small island nation rely on cavities in large trees to nest.”

“Larger trees tended to suffer more damage and mortality. These large trees store immense amounts of carbon, and in Dominica many of these large trees create unique habitats for animals, such as the parrots,” he said. “The data we obtained on how different species and sizes of trees experience damage from hurricanes can help us predict the future of these forests and the many services they provide.”

Taylor advises caution, but says that knowing how forests react to hurricanes generally applies to the hurricane-prone southern United States.

“In a field where opportunities to study a phenomenon are rare hurricanes themselves are rare events and it’s even rarer that one hits a forest plot that was measured before the hurricane hit any additional data are useful,” he said.

“That said, our study highlights that the effects of hurricanes can be very different based on the local topography and tree species that make up a forest. So comparing a small mountainous island populated by tropical rainforest trees to the forests of the coastal plains and piedmont regions of the southern United States should be approached with caution.”

In addition to DeWalt, Taylor and Stedman, the authors of the study were Professor Skip Van Bloem of the Clemson Department of Forestry and Environment Conservation and Assistant Professor Stefanie Whitmire of the Clemson Department of Agricultural Sciences.