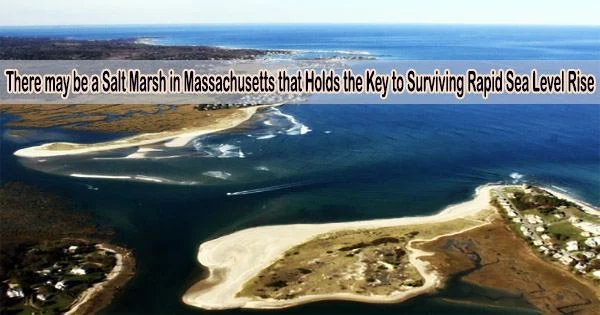

Recently, a group of scientists reported the following findings in the Journal of Geophysical Research under the direction of Brian Yellen, research professor of earth, geography, and climate sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst: Salt marshes, important habitats that are threatened by rapid sea level rise, may actually thrive despite increased water levels, according to the earth’s surface. Sediment, not water, is the primary component that affects whether salt marshes fail or thrive.

To reach this conclusion, Yellen and his colleagues looked all the way back to 1898, when the Portland Gale, a vicious Nor’easter, battered the Massachusetts coast with hurricane-force winds, buckets of rain, and a ten-foot storm surge, which remade the North-South Rivers Estuary, in Scituate, just south of Boston.

Before 1898, the North River turned sharply to the south-east on its journey to the Atlantic Ocean, meandering for about three and a half miles behind a barrier beach before joining the South River at what is now the well-known Rexhame Beach, where both rivers finally emptied into the sea.

However, the North River’s route was shortened by three and a half miles when the Portland Gale struck in late November and blasted a hole in the northern end of the barrier beach. The newly reduced tidal river had high tides that climbed by at least a foot right away, indicating the kind of sea level rise that experts predict the world will experience by the end of the century.

“It was a terrible storm,” says Yellen. “But it provided us with the rarest of things a real-world, long-term experiment showing us how salt marshes, like those along the North River Estuary, may respond to rapid sea level rise in the coming years.”

We treat sediment as if it’s trash, but it’s really treasure. It makes up the beaches that we love to play on, and the salt marshes that support both endangered birds and commercially important fish stocks. It’s time to stop treating sediment like waste.

Professor Brian Yellen

The loss of salt marshes, which are not only crucial habitats for migratory birds and young fish stocks but also offer a variety of essential ecosystem services like protecting coastlines from storm damage and filtering contaminants from runoff, is one of the many threats posed by rising ocean levels. The rapid flooding of Scituate’s wetlands is not a fatal blow, despite what one might assume.

“The salt marsh is thriving,” says Yellen.

“Salt marshes are made up of three things,” he continues. “Water, plants and sediment.”

The team proposes that even under extremely adverse conditions, such as the Portland Gale, the salt marshes can recover and adapt to their changing environment because the high coastal bluffs bordering the coast near the North River Estuary provide an abundant supply of sediment as they slowly erode into the ocean.

But historically, sediment has been seen as a concern, particularly in estuaries. Shipping routes get congested by sediment, and mudflats become unsightly to many. Dredging deep channels and transporting the removed sediment a great distance out to sea have long been accepted practices. Dams further upstream have also lessened the amount of sediment that flows from the interior to the coast.

“We treat sediment as if it’s trash,” says Yellen, “but it’s really treasure. It makes up the beaches that we love to play on, and the salt marshes that support both endangered birds and commercially important fish stocks. It’s time to stop treating sediment like waste.”

Yellen is quick to clarify that where dredging is unavoidable, there needs to be a compensatory re-infusion of material into the impacted estuary system. He is not, however, arguing for the termination of dredging and coastal navigation or the removal of all dams.

This work, which was supported by the US Geological Survey and the Department of the Interior’s Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, is only the beginning, and Yellen and his colleagues have already teamed up with a dozen public stakeholders from all the New England states to further investigate how best to confront the risks posed by climate change to New England’s shoreline.