The flu virus, often known as the influenza virus, is a highly contagious virus that mostly infects humans and other animals’ respiratory tracts. It enters our cells and “hacks” them in order to proliferate and spread.

Acute respiratory infection occurs during influenza outbreaks caused by influenza A or B viruses. Every year, they kill half a million people globally. These viruses can also cause havoc in animals, as seen with avian flu.

A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has discovered how the influenza A virus enters cells and infects them. It begins its infection cycle by attaching itself to a receptor on the cell surface and hijacking the iron transport pathway. The researchers were also able to drastically diminish its ability to infiltrate cells by inhibiting the receptor involved. These findings, which were published in the journal PNAS, show a vulnerability that could be used to tackle the virus.

Influenza viruses pose a significant threat to human and animal health. Their ability to mutate makes them highly elusive. ”We were previously aware that the influenza A virus links to sugar structures on the cell surface before rolling down the surface until it finds an appropriate entrance point inside the host cell. We didn’t know which proteins on the host cell surface marked this entry point or how they aided virus entry,” says Mirco Schmolke, Associate Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Medicine and the Geneva Centre for Inflammation Research (GCIR) at the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine, who led this research.

‘The influenza virus enters the cell and infects it by taking advantage of the continual recycling of the transferrin receptor 1. We blocked influenza A from entering cells that are ordinarily sensitive to infection by eliminating it.

Béryl Mazel-Sanchez

A receptor as a key to infection

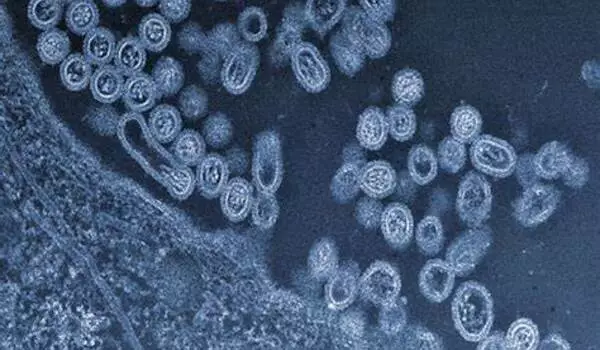

The scientists first identified cell surface proteins present in the vicinity of the viral haemagglutinin, the protein used by the influenza A virus to enter the cell. One of these proteins stood out: transferrin receptor 1. This acts as a revolving door transporting iron molecules into the cell, which are essential for many physiological functions.

”The influenza virus enters the cell and infects it by taking advantage of the continual recycling of the transferrin receptor 1,” explains Béryl Mazel-Sanchez, a former postdoctoral researcher in Mirco Schmolke’s laboratory and the study’s first author. ”To corroborate our results, we genetically altered human lung cells to either delete or overexpress the transferrin receptor 1. We blocked influenza A from entering cells that are ordinarily sensitive to infection by eliminating it. In contrast, by overexpressing it in typically resistant to infection cells, we made them more susceptible to infection”.

Inhibiting this mechanism

The researchers were subsequently able to replicate this technique by blocking the transferrin receptor 1 using a chemical compound. ”We successfully tested it on human lung cells, human lung tissue samples, and mice with various virus strains,” adds Béryl Mazel-Sanchez.

The virus multiplied substantially less in the presence of this inhibitor. This substance, however, cannot be utilized to treat humans due to its potentially carcinogenic properties.” On the other hand, anti-cancer medicines based on transferrin receptor inhibition are being developed and may be of interest in this context.

”Our discovery was made possible by outstanding collaboration within the Faculty of Medicine, as well as with the University Hospitals of Geneva (HUG) and the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB),” the authors write. In addition to the transferrin receptor 1, scientists have discovered 30 other proteins that have a function in influenza. The entry procedure is yet unknown. It is very likely that the virus employs a mix of additional receptors.

”Although we are still a long way from clinical trials, inhibiting transferrin receptor 1 could be a promising technique for treating influenza virus infections in humans and potentially in animals.”