The brains and inner ears of two British spinosaurs have been rebuilt by researchers from the University of Southampton and Ohio University, shedding light on how these enormous predatory dinosaurs interacted with their surroundings.

Spinosaurs are a type of theropod dinosaur having long, crocodile-like jaws and conical teeth. These changes enabled them to enjoy a semi-aquatic existence that included stalking riverbanks in search of prey, including huge fish. This lifestyle was substantially different from that of other theropods, such as Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus.

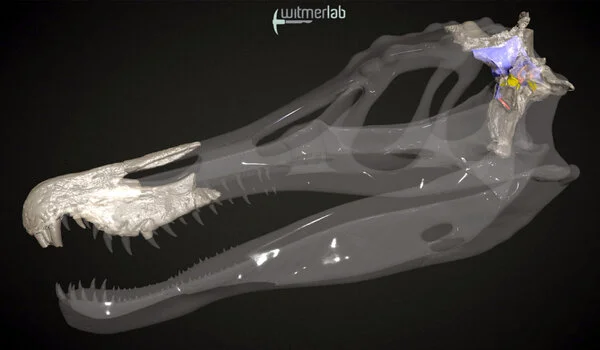

The scientists scanned fossils of Baryonyx from Surrey and Ceratosuchops from the Isle of Wight to better understand the evolution of spinosaur brains and senses. These are the oldest spinosaurs for whom braincase material has been discovered. The massive beasts would have roamed the world some 125 million years ago. Both specimens’ braincases are well preserved, and the researchers digitally rebuilt the inside soft tissues that had long rotted away.

This new research is just the latest in what amounts to a palaeontology revolution due to advances in CT-based imaging of fossils. We can now assess the cognitive and sensory capabilities of extinct animals and investigate how the brain evolved in behaviorally extreme dinosaurs like spinosaurs.

Lawrence M. Witmer

The researchers discovered that the olfactory bulbs, which process scents, were underdeveloped, and that the ear was presumably tuned to low-frequency sounds. Parts of the brain involved in keeping the head stable and the eyes concentrated on prey may have been less developed in earlier, more specialized spinosaurs.

Findings are due to be published in the Journal of Anatomy.

“Despite their unusual ecology, it seems the brains and senses of these early spinosaurs retained many aspects in common with other large-bodied theropods – there is no evidence that their semi-aquatic lifestyles are reflected in the way their brains are organised,” said the University of Southampton Ph.D. student Chris Barker, who led the study.

One interpretation of this data is that spinosaurs’ theropod ancestors already had brains and sensory adaptations for part-time fish capture, and that ‘all’ spinosaurs needed to do to become specialized for a semi-aquatic existence was to acquire a distinctive snout and teeth.

“Because the skulls of all spinosaurs are so specialized for fish-catching, it’s surprising to see such ‘non-specialized’ brains,” said Dr. Darren Naish, a contributing author. “However, the findings are still significant.” It’s amazing to learn so much about sensory capacities from British dinosaurs, including as hearing, smell, balance, and so on. “We basically extracted all the brain-related information we could from these fossils using cutting-edge technology,” Dr Naish explained.

Over the last few years, the EvoPalaeo Lab at the University of Southampton has conducted substantial research on new spinosaurs from the Isle of Wight. Ceratosuchops itself was only announced by the team in 2021, and its discovery was followed up by the publication of another new spinosaur – the gigantic White Rock spinosaur – in 2022. The braincase of Ceratosuchops was scanned at the ?-Vis X-ray Imaging Centre at the University of Southampton, home to some of the most powerful CT scanners in the country, and a model of its brain will be on display alongside its bones at Dinosaur Isle Museum in Sandown, on the Isle of Wight.

“This new research is just the latest in what amounts to a palaeontology revolution due to advances in CT-based imaging of fossils,” said co-author Lawrence M. Witmer, professor of anatomy at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, who has been CT scanning dinosaurs for over 25 years, including Baryonyx. “We can now assess the cognitive and sensory capabilities of extinct animals and investigate how the brain evolved in behaviorally extreme dinosaurs like spinosaurs.”

“This new study highlights the significant role British fossils have in our constantly evolving, fast-moving understanding of dinosaurs, and shows how the UK – and the University of Southampton in particular – is at the forefront of spinosaur research,” said Dr Neil Gostling, director of the University of Southampton’s EvoPalaeoLab. “Spinosaurs are one of the most contentious of all dinosaur groups, and this study adds to ongoing debates about their biology and evolution.”