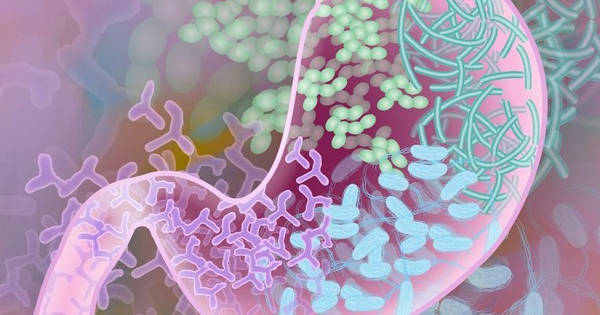

The gut microbiota has emerged as an important role in human health maintenance, influencing not just the GI tract but also distal organs like the brain, liver, and pancreas. As a result, dysbiosis, which refers to changes in the composition and function of the gut microbiome, contributes to the development of a variety of pathological illnesses such as obesity, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer. Notably, the bacterial infection has the potential to cause cancer.

A new study summarizes current knowledge about the relationship between the gut microbiota and therapeutic response to immunotherapy, chemotherapy, cancer surgery, and other treatments, pointing to ways the microbiome could be targeted to optimize treatment.

The gut microbiota has been implicated in cancer and shown to modulate anticancer drug efficacy. Altered gut microbiota is associated with resistance to chemo drugs or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), whereas supplementation of distinct bacterial species restores responses to the anticancer drugs.

We know that a healthy gut is critical to our overall health. Our stomach is so vital that it is frequently referred to as our “second” brain. In recent years, we’ve learned to recognize the gut’s various roles, including the gut-brain connection and the gut-immune system relationship.

Khalid Shah

Since ancient times, many elements of human health have been assumed to be influenced by our gut microbiome, which is home to a wide number of bacteria, viruses, fungus, and other microbes. Recently, sequencing technology has demonstrated that it may also play a role in cancer treatment. A review paper published in JAMA Oncology by Brigham and Women’s Hospital researchers captures the current understanding of the relationship between the gut microbiome and therapeutic response to immunotherapy, chemotherapy, cancer surgery, and other treatments, pointing to ways that the microbiome could be targeted to improve treatment.

“We know that a healthy gut is critical to our overall health,” said main author Khalid Shah, MS, Ph.D., of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Stem Cell and Translational Immunotherapy in the Department of Neurosurgery. “Our stomach is so vital that it is frequently referred to as our “second” brain. In recent years, we’ve learned to recognize the gut’s various roles, including the gut-brain connection and the gut-immune system relationship. Gut malfunction, or dysbiosis, on the other hand, can be harmful to human health.”

Shah and colleagues describe an increasing role of gut bacteria in immunotherapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and immune checkpoint blockade therapy are innovative cancer treatments, however, their efficacy varies greatly between individuals and cancer types. Several studies have revealed differences in the species of bacteria detected in fecal samples from responders and non-responders, implying that distinct microbiome compositions may influence clinical results.

Other research suggests that nutrition and probiotics (living bacterial species that can be consumed), as well as antibiotics and bacteriophages, can impact the composition of the gut microbiome and, as a result, the response to immunotherapy. The authors, in particular, highlight recent studies on the impact of ketogenic diets on cancer patients.

“Today, developing treatments that sync immunotherapies and gut microbiota provides medicine a unique opportunity to truly effect change in patient care,” said Shah.

The authors also discuss how bacteria have been implicated in influencing response to chemotherapy and other traditional cancer treatments, as well as how cancer medications may influence the microbiome and create side effects.

“Overall, these data suggest the possibility of modifying the gut microbiota to reduce the negative effects of traditional cancer treatment,” Shah added.

The authors point out that there is limited understanding of what “optimal” bacteria consortia in the gut look like and how findings from preclinical models may or may not translate into human applications. They emphasize the importance of exercising caution when utilizing probiotics or making dietary adjustments. Many cancer clinical studies are presently investigating the role of the microbiome in addressing some of the limitations and gaps in understanding. Trials of fecal microbial transplantation, nutritional supplements, and new medications that may impact microbiota composition are among them.

“There is compelling evidence that the gut microbiome can influence cancer therapy,” Shah added. “There are still fascinating options to investigate, such as the impact of a healthy diet, probiotics, innovative medicines, and other factors.”

Disclosures: Shah has shares in and serves on the Board of Directors of AMASA Therapeutics, a firm exploring stem cell-based cancer therapeutics; Shah’s interests have been evaluated and are managed in compliance with conflict-of-interest procedures at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare. There were no additional disclosures noted.