According to new research that combines an examination of shells from long-lived ocean quahogs and climate model simulations, rapid 20th century warming in the Gulf of Maine has reversed long-term cooling that occurred there over the previous 900 years.

According to the paper “Rapid 20th century warming reverses 900-year cooling in the Gulf of Maine,” published in Communications Earth & Environment, an open access journal from Nature Portfolio, the warming is “likely due to increased atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and changes in western North Atlantic circulation.”

“Given future projections of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and [Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation] strength, this warming trend in the Gulf of Maine is likely to continue, leading to continued and potentially worsening ecologically and economically devastating temperature increases in the region in the future,” the paper states.

“What this paper shows — both from the clams and from the climate model simulations — is that in the late 1800s, there were some pretty dramatic changes, and the Gulf of Maine began to warm, reversing 900 years of cooling caused primarily by volcanoes,” said Nina Whitney, the paper’s lead author. Whitney is a NOAA Climate and Global Change Postdoctoral Fellow in the Physical Oceanography department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), where the research presented in this paper began.

The findings are significant because they reveal when the recent warming in the Gulf of Maine began and the likely causes of the warming. Both the clams and the climate model simulations suggest that greenhouse gas forcings are not only likely causing surface temperature changes affecting the Gulf of Maine, but also causing changes in ocean circulation.

Alan Wanamaker

“Both the clams and the climate model simulations suggest that greenhouse gas forcings are not only likely causing surface temperature changes affecting the Gulf of Maine, but also causing changes in ocean circulation. The pathways and the strengths of different ocean currents bringing water into the Gulf of Maine have changed as the region has warmed,” Whitney says.

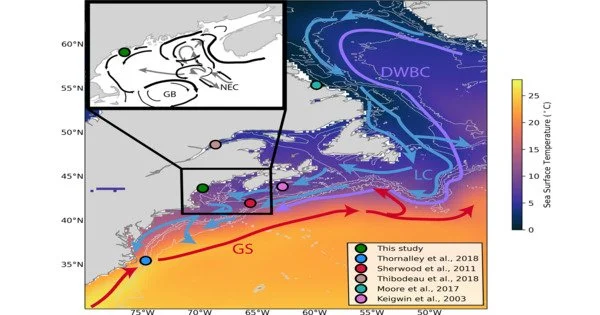

Scientists used geochemical records of oxygen, nitrogen, and previously published radiocarbon isotopes from Arctica islandica (ocean quahog) shells from the Gulf of Maine to reconstruct 300 years of hydrographic variability.

According to Whitney, the ocean quahogs, which can live up to 500 years and grow their shells in annual increments similar to tree rings, were absolutely dated by the researchers and served as good recorders of ocean conditions.

The chemical signatures from the shells provided researchers with a multi-proxy approach to study changes in ocean conditions. Oxygen isotopes served as a proxy for seawater temperature and salinity; nitrogen and radiocarbon isotopes were proxies for water mass source. Researchers put the geochemical results into a broader temporal and spatial context by analyzing fully-coupled climate model simulations from the Community Earth System Model-Last Millennium Ensemble.

“The observed rate of warming in the Gulf of Maine over the last century has outpaced average global ocean warming. This has extensive consequences for the region’s ecosystems and fisheries, and thus for the local economy,” says paper co-author Caroline Ummenhofer, associate scientist in WHOI’s Physical Oceanography Department.

“Our new study combines paleo proxy evidence from bivalves with climate models to put the rapid warming in the Gulf of Maine into context over time. Using a cutting-edge set of climate model simulations, we can distinguish between ocean temperature trends caused by internal climate dynamics and those caused by anthropogenic influences. We discover that the rate of warming in the Gulf of Maine since the early twentieth century stands out in the context of the last 1000 years, reversing a long-term multi-century cooling trend that existed up until the late 1800s. In a warming climate, such long-term context is critical for adapting regional fisheries and managing natural resources in vulnerable marine ecosystems” Ummenhofer says.

“The findings are significant because they reveal when the recent warming in the Gulf of Maine began and the likely causes of the warming,” says Alan Wanamaker, paper co-author and professor in Iowa State University’s Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences.

“Revisiting my Ph.D. research in the Gulf of Maine with more tools and fresh perspectives provided by Nina Whitney and the team was very satisfying,” Wanamaker says. “In reality, it took approximately 900 years to cool by 2°C and only 100 years to warm by 2°C. Unfortunately, warming in the Gulf of Maine is expected to continue and worsen in the coming decades, wreaking havoc on the entire ecosystem.”