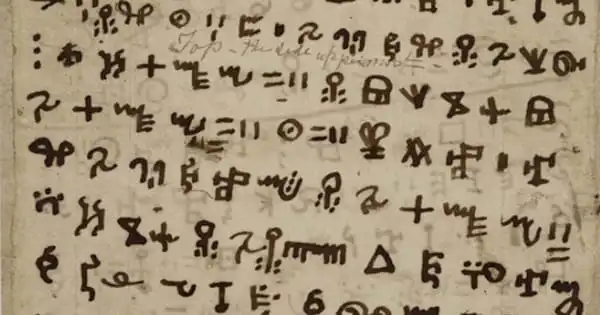

A rare script from a Liberian language has revealed new insights on how written languages emerge. According to a new study based on an analysis of an isolated West African writing system, writing evolves to become simpler and more efficient.

The world’s earliest writing was invented about 5000 years ago in the Middle East, before being reinvented in China and Central America. Today, practically all human activities rely on this technology, from schooling to political systems to computer code. Despite its importance in everyday life, we know little about how writing evolved in its early years. Because there are so few sites of genesis, the initial traces of writing are fragmented or absent entirely.

A team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, demonstrated in a recent study published in Current Anthropology that writing swiftly gets ‘compressed’ for efficient reading and writing. They used a rare African writing system that has interested outsiders since the early nineteenth century to arrive at this conclusion.

The Vai script of Liberia was established from scratch in about 1834 by eight absolutely uneducated men who wrote with ink produced from crushed berries. The Vai language had never been written down before.

Dr. Piers Kelly

“The Vai script of Liberia was established from scratch in about 1834 by eight absolutely uneducated men who wrote with ink produced from crushed berries,” explains lead author Dr. Piers Kelly, who is now at the University of New England in Australia. The Vai language had never been written down before.

“Because of its isolation and how it has evolved up to the current day, we believed it would tell us something important about how writing evolves over short periods of time.”

According to Vai teacher Bai Leesor Sherman, the script was always taught informally to a single apprentice student by a literate teacher. It is still so successful that it is utilized to deliver pandemic health messages today.

“Because of its isolation and the way it has continued to develop up to the current day,” Kelly explains, “we believed it could tell us something fundamental about how writing evolves over short periods of time.”

“A well-known theory holds that letters evolve from pictures to abstract signs. However, there are many abstract letter shapes in early writing. Instead, we projected that signals would begin relatively complicated and gradually become simpler as new generations of writers and readers came of age.”

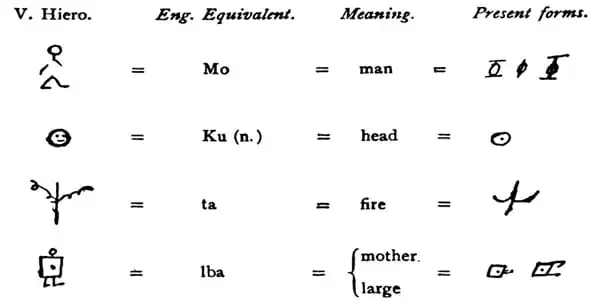

The researchers examined writings in the Vai language from Liberia, the United States, and Europe. They traced the script’s whole evolutionary history from 1834 onwards by analyzing year-by-year modifications in its 200 syllabic letters. Using computational tools to measure visual complexity, they discovered that the letters became visually simpler with each passing year.

“Dreams led the initial creators to create distinct signs for each word of their language. One depicts a pregnant lady, another a chained slave and others are adapted from traditional emblems. When these indicators were used to write spoken syllables and then taught to other people, they became simpler, more methodical, and more similar to one another “says Kelly This pattern of simplification may be seen in ancient writing systems across far longer time spans as well.

“When developing a new writing system, visual complexity is advantageous. You generate more clues and greater contrasts between signals, which aids illiterate learners. This complexity eventually comes in the way of effective reading and replication, thus it goes away” says Kelly.

Illiterate innovators in West Africa reverse-engineered writing for languages spoken in Mali and Cameroon, while new writing systems are continually being devised in Nigeria and Senegal. Nigerian philosopher Henry Ibekwe responded to the study by saying: “Indigenous African scripts continue to represent a massive, untapped repository of semiotic and symbolic information. Many questions remain unanswered.”

“However, the fact that Vai continued to compress throughout the nineteenth century, during a time when there was minimal change in writing media, suggests that shifts in writing technology cannot be the entire story,” the researchers conclude.

While the rapid emergence of this writing system is extraordinary, the researchers believe it occurred because its founders and users already knew what writing was capable of because they were aware of its use in other civilizations. This may have prompted the Vai team to enhance their system as soon as possible.

However, there is a trade-off between simplification and ensuring that each symbol remains distinct, which may explain why certain scripts retain their complexity. The researchers hope to look into this further.